[/caption]

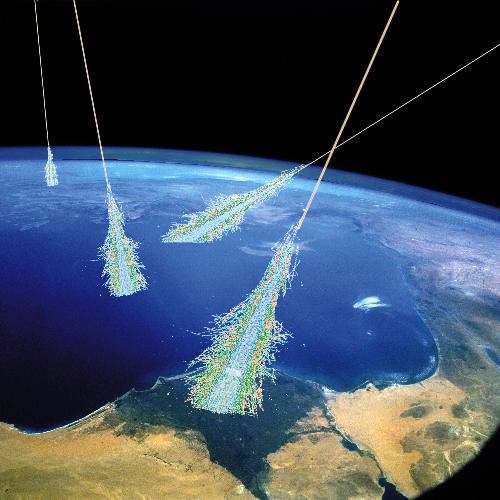

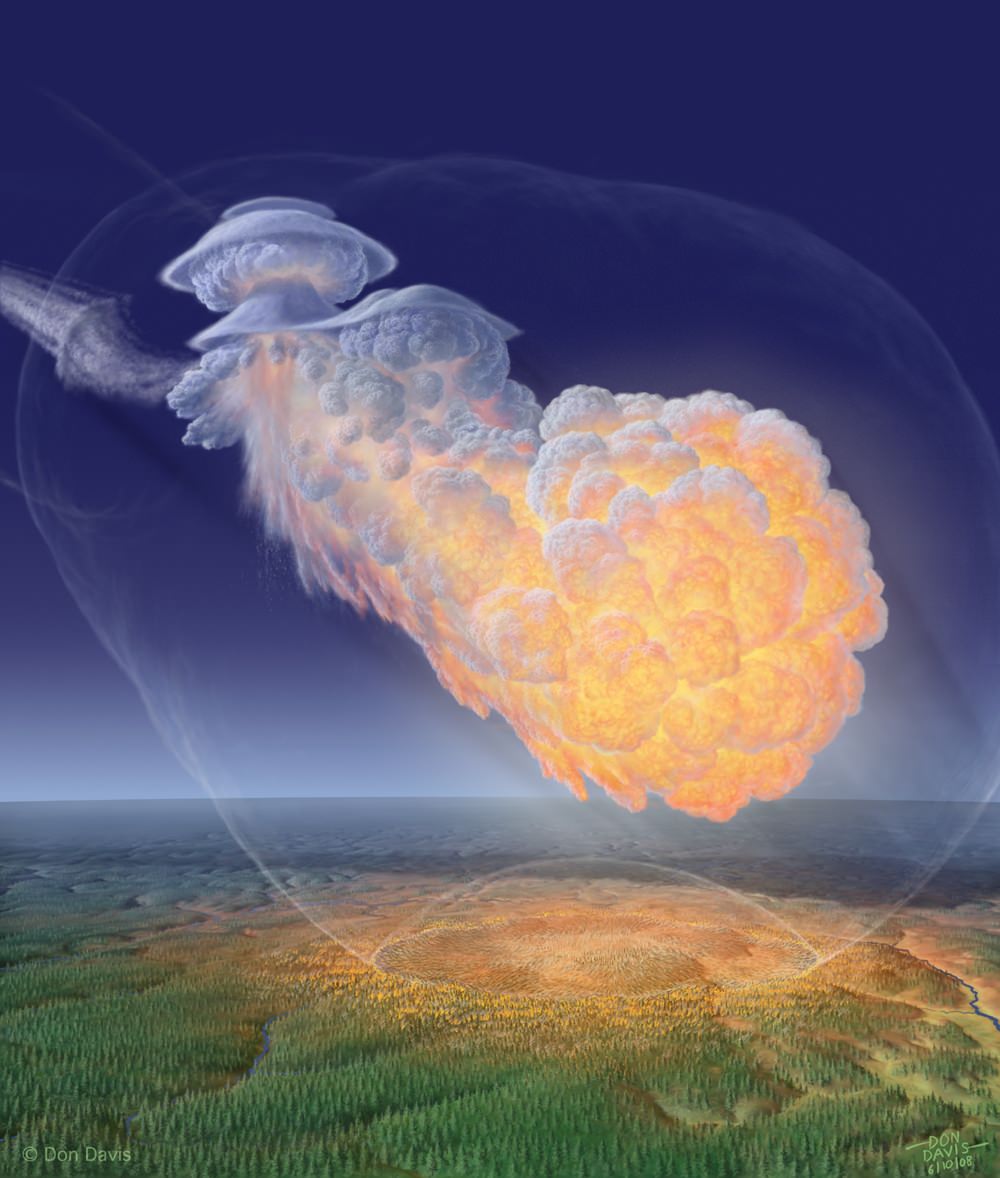

People looking for new ways to explain climate change on Earth have sometimes turned to cosmic rays, showers of atomic nuclei that emanate from the Sun and other sources in the cosmos.

But new research, in press in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, says cosmic rays are puny compared to other climatic influences, including greenhouse gases — and not likely to impact Earth’s climate much.

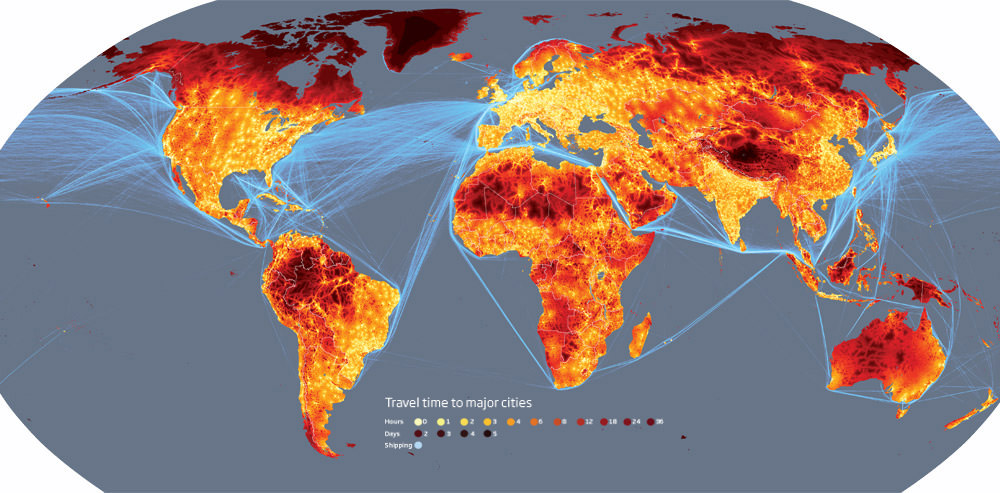

Jeffrey Pierce and Peter Adams of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, point out that cycles in numerous climate phenomena, including tropospheric and stratospheric temperatures, sea-surface temperatures, sea-level pressure, and low level cloud cover have been observed to correlate with the 11-year solar cycle.

However, variation in the Sun’s brightness alone isn’t enough to explain the effects and scientists have speculated for years that cosmic rays could fill the gap.

For example, Henrick Svensmark, a solar researcher at the Danish Space Research Institute, has proposed numerous times, most recently in 2007, that solar cosmic rays can seed clouds on Earth – and he’s seen indications that periods of intense cosmic ray bombardment have yeilded stormy weather patterns in the past.

Others have disagreed.

“Dust and aerosols give us much quicker ways of producing clouds than cosmic rays,” said Mike Lockwood, a solar terrestrial physicist at Southampton University in the UK. “It could be real, but I think it will be very limited in scope.”

To address the debate, Pierce and Adams ran computer simulations using cosmic-ray fluctuations common over the 11-year solar cycle.

“In our simulations, changes in [cloud condensation nuclei concentrations] from changes in cosmic rays during a solar cycle are two orders of magnitude too small to account for the observed changes in cloud properties,” they write, “consequently, we conclude that the hypothesized effect is too small to play a significant role in current climate change.”

The results have met a mixed reception so far with other experts, according to an article in this week’s issue of the journal Science: Jan Kazil of the University of Colorado at Boulder has reported results from a different set of models, confirming that cosmic rays’ influence is similarly weak. But at least one researcher — Fangqun Yu of the University at Albany in New York — has questioned the soundness of Pierce and Adams’ simulations.

And so, the debate isn’t over yet …

Sources: The original paper (available for registered AGU users here) and a news article in the May 1 issue of the journal Science. See links to some of Svensmark’s papers here.