[/caption]

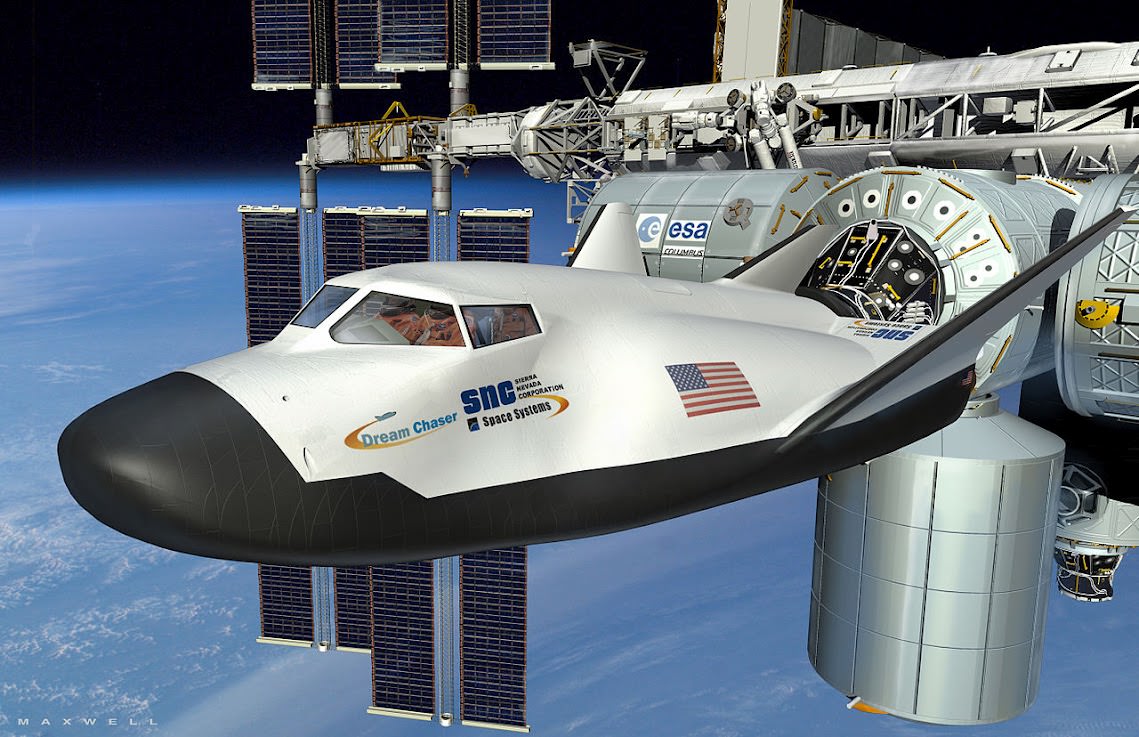

Image Caption: Dream Chaser commercial crew vehicle built by Sierra Nevada Corp docks at ISS

Commercial test pilots, not NASA astronauts, will fly the first crewed missions that NASA hopes will at last restore America’s capability to blast humans to Earth orbit from American soil – perhaps as early as 2015 – which was totally lost following the forced shuttle shutdown.

At a news briefing this week, NASA managers at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) said the agency is implementing a new way of doing business in human spaceflight and purposely wants private companies to assume the flight risk first with their crews before exposing NASA crews as a revolutionary new flight requirement. Both NASA and the companies strongly emphasized that there will be no shortcuts to flying safe.

A trio of American aerospace firms – Boeing, SpaceX and Sierra Nevada Corp – are leading the charge to develop and launch the new commercially built human-rated spacecraft that will launch Americans to LEO atop American rockets from American bases.

The goal is to ensure the nation has safe, reliable and affordable crew transportation systems for low-Earth orbit (LEO) and International Space Station (ISS) missions around the middle of this decade.

The test launch schedule hinges completely on scarce Federal dollars from NASA for which there is no guarantee in the current tough fiscal environment.

The three companies are working with NASA in a public-private partnership using a combination of NASA seed money and company funds. Each company was awarded contracts under NASA’s Commercial Crew Integrated Capability Initiative, or CCiCap, program, the third in a series of contracts aimed at kick starting the development of the so-called private sector ‘space taxis’ to fly astronauts to and from the ISS.

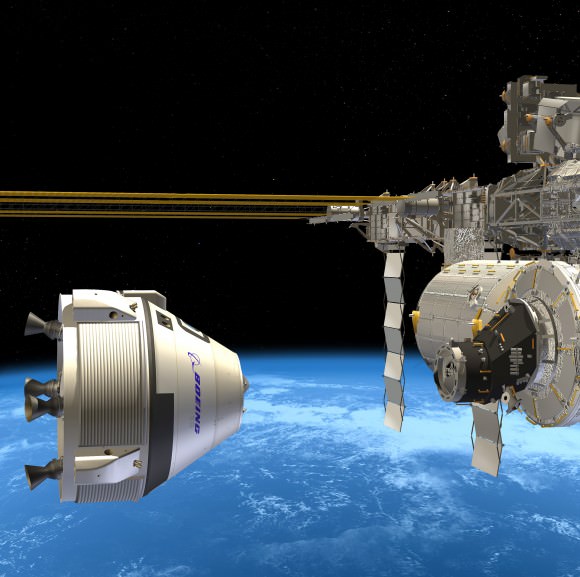

Caption: Boeing CST-100 crew vehicle docks at the ISS

The combined value of NASA’s Phase 1 CCiCap contracts is about $1.1 Billion and runs through March 2014 said Ed Mango, NASA’s Commercial Crew Program manager. Phase 2 contract awards will follow and eventually lead to the actual flight units after a down selection to one or more of the companies, depending on NASA’s approved budget.

Since the premature retirement of NASA’s shuttle fleet in 2011, US astronauts have been 100% reliant on the Russians to hitch a ride to the ISS – at a price tag of over $60 Million per seat. This is taking place while American aerospace workers sit on the unemployment line and American expertise and billions of dollars of hi-tech space hardware rots away or sits idly by with each passing day.

Boeing, SpaceX and Sierra Nevada Corp seek to go where no private company has gone before – to low Earth orbit with their private sector manned spacecraft. And representatives from all three told reporters they are all eager to move forward.

All three commercial vehicles – the Boeing CST-100; SpaceX Dragon and Sierra Nevada Dream Chaser – are designed to carry a crew of up to 7 astronauts and remain docked at the ISS for more than 6 months.

“For well over a year now, since Atlantis [flew the last space shuttle mission], the United States of America no longer has the capability to launch people into space. And that’s something that we are not happy about,” said Garrett Reisman, a former space shuttle astronaut who is now the SpaceX Commercial Crew project manager leading their development effort. “We’re very proud to be part of the group that’s going to do something about that and get Americans back into space.”

Caption: Blastoff of SpaceX Cargo Dragon atop Falcon 9 from Cape Canaveral, Florida on May, 22, 2012, bound for the ISS. Credit: Ken Kremer

“We are the emotional successors to the shuttle,” said Mark Sirangelo, Sierra Nevada Corp. vice president and SNC Space Systems chairman. “Our target was to repatriate that industry back to the United States, and that’s what we’re doing.”

Sierra Nevada is developing the winged Dream Chaser, a mini-shuttle that launches atop an Atlas V rocket and lands on a runway like the shuttle. Boeing and SpaceX are building capsules that will launch atop Atlas V and Falcon 9 rockets, respectively, and then land by parachute like the Russian Soyuz capsule.

SpaceX appears to be leading the pack using a man-rated version of their Dragon capsule which has already docked twice to the ISS on critical cargo delivery missions during 2012. From the start, the SpaceX Dragon was built to meet the specification ratings requirements for a human crew.

Caption: Dragon spacecraft approaches the International Space Station on May 25, 2012 for grapple and berthing . Photo: NASA

Reisman said the first manned Dragon test flight with SpaceX test pilots could be launched in mid 2015. A flight to the ISS could take place by late 2015. Leading up to that in April 2014, SpaceX is planning to carry out an unmanned in-flight abort test to simulate and test a worst case scenario “at the worst possible moment.”

Boeing is aiming for an initial three day orbital test flight of their CST-100 capsule during 2016, said John Mulholland, the Boeing Commercial Programs Space Exploration vice president and program manager. Mulholland added that Chris Ferguson, the commander of the final shuttle flight by Atlantis, is leading the flight test effort.

Boeing has leased one of NASA’s Orbiter Processing Facility hangers (OPF-3) at KSC. Mulholland told me that Boeing will ‘cut metal’ soon. “Our first piece of flight design hardware will be delivered to KSC and OPF-3 within 5 months.”

Caption: Boeing CST-100 capsule mock-up, interior view. Credit: Ken Kremer

Sierra Nevada plans to start atmospheric drop tests of an engineering test article of the Dream Chaser from a carrier aircraft in the next few months in an autonomous mode. The test article is a full sized vehicle.

“It’s not outfitted for orbital flight; it is outfitted for atmospheric flight tests,” Sirangelo told me. “The best analogy is it’s very similar to what NASA did in the shuttle program with the Enterprise, creating a vehicle that would allow it to do significant flights whose design then would filter into the final vehicle for orbital flight.”

Now to the issue of using commercial space test pilots in place of NASA astronauts on the initial test flights.

At the briefing, Reisman stated, “We were told that because this would be part of the development and prior to final certification that we were not allowed, legally, to use NASA astronauts to be part of that test pilot crew.”

So I asked NASA’s Ed Mango, “Why are NASA astronauts not allowed on the initial commercial test flights?”

Mango replied that NASA wants to implement the model adopted by the military wherein the commercial company assumes the initial risk before handing the airplanes to the government.

“We would like them to get to a point where they’re ready to put their crew on their vehicle at their risk,” said Mango. “And so it changes the dynamic a little bit. Normally under a contract, the contractor comes forward and says he’s ready to go fly but it’s a NASA individual that’s going to sit on the rocket, so it becomes a NASA risk.

“What we did is we flipped it around under iCAP. It’s not what we’re going to do long term under phase two, but we flipped it around under iCAP and said we want to know when you’re ready to fly your crew and put your people at risk. And that then becomes something that we’re able to evaluate.”

“In the end all our partners want to fly safe. They’re not going to take any shortcuts on flying safe,” he elaborated. “All of us have the same initiative and it doesn’t matter who’s sitting on top of the vehicle. It’s a person, and that person needs to fly safely and get back home to their families. That’s the mission of all our folks and our partners – to go back home and see their family.”

Given the nations fiscal difficulties and lack of bipartisan cooperation there is no guarantee that NASA will receive the budget it needs to keep the commercial crew program on track.

Indeed, the Obama Administrations budget request for commercial crew has been repeatedly slashed by the US Congress to only half the request in the past two years. These huge funding cuts have already forced a multi-year delay in the inaugural test flights and increased the time span that the US has no choice but to pay Russia to launch US astronauts to the ISS.

“The budget is going to be an extremely challenging topic, not only for this program but for all NASA programs,” said Phil McAlister, NASA Commercial Spaceflight Development director.

NASA is pursuing a dual track approach in reviving NASA’s human spaceflight program. The much larger Orion crew capsule is simultaneously being developed to launch atop the new SLS super rocket and carry astronauts back to the Moon by 2021 and then farther into deep space to Asteroids and one day hopefully Mars.

Caption: Dream Chaser awaits launch atop Atlas V rocket

![Dream_Chaser_Atlas_V_Integrated_Launch_Configuration[1]](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Dream_Chaser_Atlas_V_Integrated_Launch_Configuration1-315x580.jpg)

Come to think of it, how is NASA doing post shuttle? Has the money situation been easier for them, or has the government decided to continue to reduce its budget?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Budget_of_NASA

What a phenomenal page. Thank you for sharing. In inflation adjusted dollars it hasn’t been steadily declining, but it’s been pretty much static since we cancelled Apollo.

The retirement of the Shuttle fleet in2011 could hardly be described as “premature”. The true failure was not to develop suitable alternatives in due time.

True. It’s just Ken Kremer’s thang to make a Space Shuttle obituary out of any story…even when the topic at hand is really SpaceX’s exciting announcement that they are just two years from crewed flights with their own test-pilot astronauts.

Good work SpaceX.

I was most of the way through writing a 1500 word response that agreed with you, but it occurred to me that no one ever reads those, heh. So here’s the really, really cut down, low detail version:

Not every part on the shuttles could be replaced. Every shuttle was already at or near its maximum rated lifetime. Because of this the only way to persevere the shuttle program would have been to build entirely new shuttles at great expense.

And that’s fine. But why not take that great expense and do something else with it instead? Why rehash 40 year old technology that never really worked properly in the first place when we could start from scratch and build something new? We could have spent that money on VentureStar, a redesign of the X-37 project, or a new and improved version of the HL-20 (or a better version of the DC-X for that matter). All and any of those would have been worthy successors to the shuttle program. They’d have been more capable and – likely – cheaper as well. That’s not what happened, but it’s what could have happened… and what might still happen after the SLS is eventually cancelled.

I don’t agree with the path NASA was eventually forced to take (Constellation, which was eventually parred down into the SLS), but disagreeing with the path taken isn’t the same as disagreeing with the entirely correct decision to

Contellation was a programmatic failure. Given Apollo funding, it may well have been a fine rocket system. But NASA has taken cuts at pretty much every opportunity since Nixon. What remains simply couldn’t have sustained Constellation. And the blame is bipartisan on it. Bush put forward the vision and approved the program, yet within months cut its budget. And he cut the NASA budget in general and the Constellation budget in specific every single year after that. And congress, despite a few heroic efforts, largely went along with the cuts, no matter which party was in charge.

As to it’s performance, it was exactly as far from launch, 7 years, on the day it was cancelled as the day it was announced. In the intervening years, 9 billion was spent on a SRB with a dummy payload on top, the permanent base was reduced down to a series of two week sorties a la Apollo, and Ares V was kicked out into the middle of the 2020’s before it even saw a single pice of metal cut. Huge segments of the science budget were cut in the process including a number of missions meant to be precursors to Moon bases and Mars missions. Orion, on the other hand, adapted to the repeated performace downgrades of Ares I and budget trimming, and resulted in a capsule I’m glad we developed and decided to keep.

SLS had some potential with the first options on the table, and perhaps it still does. But congress insisted on a 130t rocket NASA never asked for and didn’t need. And with the budget moving in the same direction it has for the past 50 years, I fear it will look a lot like Constellation in just a few years. I hope it succeeds. I really do. We need multiple options on the table, and I’d be happy to have SLS fly from our shores. I just worry that it will become another funding sink.

We need something to replace shuttle. Ares wasn’t it. I’m not yet convinced Constellation is either. I really hope I’m wrong.

Thanks to Zoutsteen for clarifying on the budget. It has been steady versus going down. But steady isn’t enough for either of our recent shuttle replacement options.

It isn’t even steady. The dollar amount may be steady for the next few budgets (*may be*, we don’t yet know for sure), but in real terms funding is going down. If nothing else inflation has been slowly chipping away NASA’s budget Since the mid sixties.

Actually, the page he references has a 2007 standard dollars column that should account for the approximated inflation rate. With that factored in there have been a few periods where the funding has gone up, including the first few years of the Obama admin, but the increases have never been more than a billion or two and it has only gone up for a year or two before slumping again. In the last 20 years it has wobbled up and down, but stayed pretty steady between 14 and 18 billion 2007 dollars. That’s total NASA funding, mind you, and doesn’t address the individual accounts within the wider budget.

Also, to clarify, at least with the understanding we have now, none of the X programs were intended for interplanetary travel. Interplanetary reentry velocities would quickly and violently rip off anything resembling a wing. There are strategies to mitigate that, but for the moment no proposed ‘shuttle’ style craft would be anything more than a LEO tug, a la DreamChaser. We certainly need one of those, and in a bad way, but it is not the answer to the interplanetary equation. DreamChaser is, in fact, the product of not one, but two X Plane designs that started within the walls of NASA (more one than the other). It’s a great little spaceplane and the canning of its predecessors was truly unfortunate, just as the similar abandonment of Transhab, which became Bigelow when Bigelow got the Space Act contracts, was shortsighted. But DreamChaser is forever relegated to circle around our planet.

I’d counter that LEO capsules and spaceplanes are *exactly* what we need for interplanetary travel. Any trip to Mars (or any other destination, including Luna) in a capsule is too expensive to seriously contemplate.

For interplanetary travel to work we need to let go of the notion that you have to launch your “ship” from ground to destination. The only logical way to engage in such an endeavour is to use permanent in-space spacecraft which never touch the ground of either Earth or their destination. Travel to and from Earth (to the ship) would be done using spaceplanes, while travel to and from the destination (say, Luna) would be done using a lander that you lug along for the ride.

That’s the *only* reasonable way do it. Launching a capsule straight from Earth to Luna or a planet is a losing strategy. Too expensive, too difficult logistically, and too dangerous.

gopher – I could be wrong but I seem to recall when the shuttle program began the shuttles were supposed to be good for 100 flights each and the SRB’s were supposed to be good for 25 flights each. How were the shuttles beyond their max rated lifetime? The shuttle problem, as is well known, was that there were fundamental design issues with it, and IMHO, Bush did the right thing by retiring them once the ISS was completed – otherwise it was simply a matter of time before there were more Columbias and Challengers and NASA already had a bit of a black eye over it.

It is the right thing to do to put what is to some extent a mature enough technology (i.e. getting people and things to LEO) in the hands of the private sector in order to let businesses do their thing and bring the cost down, and to force NASA do concentrate on the next big thing (i.e. solving the problems of getting people safely beyond LEO). The problem is that they need some clear vision and some (fiscal) commitment from the government so that they don’t wind up with an overly compromised design again. They have neither at the moment.

The true failure was developing Shuttle in the first place. $2 billion a year whether it launched or not.

Without STS no ISS as we know it. The result would have by necessity looked more Mir like.

The resulting modules can make an interplanetary craft/waystations. But we don’t need SLS for any of it, and if we keep the core going we shouldn’t need an STS replacement either.

The main mistake was to try for an expensive NASA+military tool-for-all-trades. Other system mistakes was to put the crew alongside three launch stages instead of more safely on top, et cetera: it is a long list since it was a unique craft.

Lessons learned goes into Dreamchaser, showing the concept isn’t without merits.

STS could have been built the same way Skylab was built. The same way Mir was built. One Skylab has about 1/3 the pressurized volume of IIS.

Hubble rescue would have been difficult.

But overall the program would have been much safer, and perhaps a bit cheaper, without Shuttle. And we would have never lost our heavy launch capability to an underbuilt and over designed brick.

Both Skylab and Mir was launched “as is” compartments, which was my point. ISS was built piecemeal, by STS.

Are you being intentionally obtuse? My point is, lacking Shuttle, an IIS analog would have been built, certainly piecemeal, by Saturn V, and it’s descendants.

And no, Mir was a hodgepodge built up over many flights.

> “And representatives from all three told reporters they are all eager to move forward.”

NO WAY.

Oh dear! This will put Musk on the spot, will he be an early LEO crew or not?

But it is a good idea, making the technology pay-for-the key available and harmonizing with other governmental contracts.

The SLS pork politicians tried to strangle both commercial cargo and crew before, so that SLS would be the only, too expensive, option. But they had to back off due to the political pressure that puts on them.

My guess is that commercial crew will be strangled enough that it will be later than SLS is ready for LEO, but that the porkers will have to be satisfied with an early SLS LEO docking mission out of it.

That puts commercial crew service somewhere early in the 20’s, I think.

Anyone who flies in a crude spaceship is an idiot.