NASA took another big step on the path to propel our astronauts back to deep space and ultimately on to Mars with the long awaited decision to formally restart production of the venerable RS-25 engine that will power the first stage of the agency’s mammoth Space Launch System (SLS) heavy lift rocket, currently under development.

Aerojet Rocketdyne was awarded a NASA contract to reopen the production lines for the RS-25 powerplant and develop and manufacture a certified engine for use in NASA’s SLS rocket. The contract spans from November 2015 through Sept. 30, 2024.

The SLS is the most powerful rocket the world has ever seen and will loft astronauts in the Orion capsule on missions back to the Moon by around 2021, to an asteroid around 2025 and then beyond on a ‘Journey to Mars’ in the 2030s – NASA’s overriding and agency wide goal. The first unmanned SLS test flight is slated for late 2018.

The core stage (first stage) of the SLS will initially be powered by four existing RS-25 engines, recycled and upgraded from the shuttle era, and a pair of five-segment solid rocket boosters that will generate a combined 8.4 million pounds of liftoff thrust, making it the world’s most powerful rocket ever.

The newly awarded RS-25 engine contract to Sacramento, California based Aerojet Rocketdyne is valued at 1.16 Billion and aims to “modernize the space shuttle heritage engine to make it more affordable and expendable for SLS,” NASA announced on Nov. 23. NASA can also procure up to six new flight worthy engines for later launches.

“SLS is America’s next generation heavy lift system,” said Julie Van Kleeck, vice president of Advanced Space & Launch Programs at Aerojet Rocketdyne, in a statement.

“This is the rocket that will enable humans to leave low Earth orbit and travel deeper into the solar system, eventually taking humans to Mars.”

The lead time is approximately 5 or 6 years to build and certify the first new RS-25 engine, Van Kleek told Universe Today in an interview. Therefore NASA needed to award the contract to Aerojet Rocketdyne now so that its ready when needed.

The RS-25 is actually an upgraded version of former space shuttle main engines (SSMEs) originally built by Aerojet Rocketdyne.

The reusable engines were used with a 100% success rate during NASA’s three decade-long Space Shuttle program to propel the now retired shuttle orbiters to low Earth orbit.

Those same engines are now being modified for use by the SLS on missions to deep space starting in 2018.

But NASA only has an inventory of 16 of the RS-25 engines, which is sufficient for a maximum of the first four SLS launches only. Although they were reused numerous times during the shuttle era, they will be discarded after each SLS launch.

And since the engines cannot be recovered and reused as during the shuttle era, a brand new set of RS-25s will have to be manufactured from scratch.

Therefore, the engine manufacturing process can and will be modernized and significantly streamlined – using fewer part and welds – to cut costs and improve performance.

“The RS-25 engines designed under this new contract will be expendable with significant affordability improvements over previous versions,” added Jim Paulsen, vice president, Program Execution, Advanced Space & Launch Programs at Aerojet Rocketdyne. “This is due to the incorporation of new technologies, such as the introduction of simplified designs; 3-D printing technology called additive manufacturing; and streamlined manufacturing in a modern, state-of-the-art fabrication facility.”

“The new engines will incorporate simplified, yet highly reliable, designs to reduce manufacturing time and cost. For example, the overall engine is expected to simplify key components with dramatically reduced part count and number of welds. At the same time, the engine is being certified to a higher operational thrust level,” says Aerojet Rocketdyne.

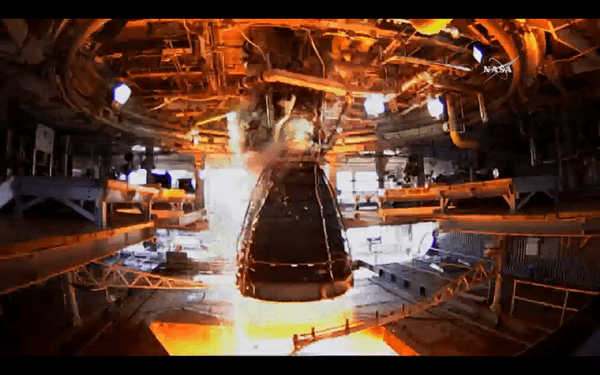

The existing stock of 16 RS-25s are being upgraded for use in SLS and also being run through a grueling series of full duration hot fire test firings to certify them for flight, as I reported previously here at Universe Today.

Among the RS-25 upgrades is a new engine controller specific to SLS. The engine controller functions as the “brain” of the engine, which checks engine status, maintains communication between the vehicle and the engine and relays commands back and forth.

Each of the RS-25’s engines generates some 500,000 pounds of thrust. They are fueled by cryogenic liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. For SLS they will be operating at 109% of power, compared to a routine usage of 104.5% during the shuttle era. They measure 14 feet tall and 8 feet in diameter.

They have to withstand and survive temperature extremes ranging from -423 degrees F to more than 6000 degrees F.

The maiden test flight of the SLS is targeted for no later than November 2018 and will be configured in its initial 70-metric-ton (77-ton) version with a liftoff thrust of 8.4 million pounds. It will boost an unmanned Orion on an approximately three week long test flight beyond the Moon and back.

NASA plans to gradually upgrade the SLS to achieve an unprecedented lift capability of 130 metric tons (143 tons), enabling the more distant missions even farther into our solar system.

The first SLS test flight with the uncrewed Orion is called Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1) and will launch from Launch Complex 39-B at the Kennedy Space Center.

Orion’s inaugural mission dubbed Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT) was successfully launched on a flawless flight on Dec. 5, 2014 atop a United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy rocket Space Launch Complex 37 (SLC-37) at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.

………….

Learn more about SLS, Orion, SpaceX, Orbital ATK Cygnus, ISS, ULA Atlas rocket, Boeing, Space Taxis, Mars rovers, Antares, NASA missions and more at Ken’s upcoming outreach events:

Dec 1 to 3: “Orbital ATK Atlas/Cygnus launch to the ISS, ULA, SpaceX, SLS, Orion, Commercial crew, Curiosity explores Mars, Pluto and more,” Kennedy Space Center Quality Inn, Titusville, FL, evenings

Dec 8: “America’s Human Path Back to Space and Mars with Orion, Starliner and Dragon.” Amateur Astronomers Assoc of Princeton, AAAP, Princeton University, Ivy Lane, Astrophysics Dept, Princeton, NJ; 7:30 PM.

This article has a more “rah, rah, NASA!” tone than most on Universe Today. It is not a welcome difference. The touch of calling SLS a “Mars Rocket” is another unwelcome step in the same direction. I’m a big fan of NASA, but we’re a long, long way from going to Mars, and NASA needs to own up to the remaining challenges.

I don’t know how officially NASA it is, but people there are talking about a mission to the moons of Mars 2031. That seems quite realistic since it would be much easier than a surface mission, and with longer stays on the ISS microgravity is becoming a familiar terrain.

Sure it could’ve been better. Undeveloping a reusable engine to a non-reusable one, is going against the current trend in the launcher business. SLS is very expensive and boringly old fashioned. But that is how government does things, everything. A government is a huge waste and destruction of society. But I rather see it doing this than something else.

It is specifically very, very Congress. NASA, ULA, and SpaceX all did presentations to Congress, several years ago, indicating that they could build heavy lift launch vehicles in half the time, and for between 1/4 and 1/2 the cost, of SLS. However, by selecting SLS over all these other proposals, Congress specified engineering aspects of the rocket that would guarantee that only certain companies – within the states and Congressional districts of influential members of Congress – would be the only companies that could possibly meet those contract needs. Consequently, we have a ridiculously expensive launch vehicle that will not make its first crewed launch until the beginning of next decade, when we could have had one launching sooner and for far less money than SLS. That’s not NASA’s fault – the fault lies squarely with Congress (and with members of both parties).

It’s at the least a bit disingenuous to talk about this remarkable machine- and indeed it is remarkable- without mentioning the stunning costs and the political turmoil associated with flying it.

Appropriate, too, would be mention of another huge rocket in development- Falcon Heavy- which while providing somewhat less throw weight initially is about a third the cost to operate and is being developed by a private company without government funds. Costs are notoriously difficult to discuss, but it’s safe to say that FH is MUCH less costly. And finally that FH is largely reusable (which remains to be proven, true).

(Yes, I know, SpaceX has contracts with NASA, and indeed received COTS funds for Falcon).

Absolutely correct. Work on the Falcon Heavy was started after SLS, and it should be flying sooner, and more often. And of course you’re correct about the relevant costs.

‘Disposable’ SSME’s? Yeah.. why not? The original design for the RS-25 predicted ten flights between overhaul and a vacuum specific impulse of 455 seconds. Neither goal was achieved – vacuum impulse was 453 seconds, and the engines had to be pulled, inspected, and refurbished after each flight. And THAT cost a lot of $$! Ergo the logic about single use for the STS? Still, I’d have preferred to have seen a more robust design like ULA’s Vulcan concept? Or SpaceX’s heavy lift with it’s soft landing concept. With the Vulcan, the rocket engine assembly separates from the 1st stage booster. then re-enters the atmosphere separately and parachutes down for recovery. Not quite as good as SpaceX’s concept, but still has a potential cost savings.

Will those engines also have to be extensively inspected and refurbished after each flight? Presumably so, even though the engine module will be recovered by helicopter instead of using a more corrosive ocean landing and recovery.