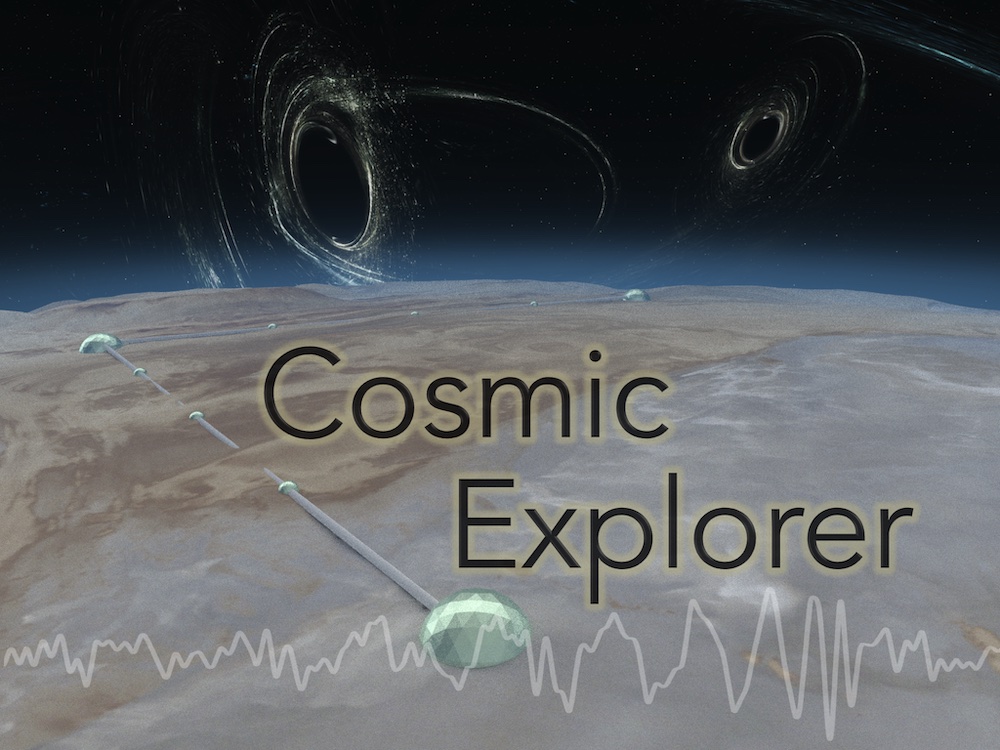

Gravitational astronomy is a relatively new discipline that has opened many doors for astronomers to understand how the huge and violent end of the scale works. It has been used to map out merging black holes and other extreme events throughout the universe. Now a team from Cal Tech’s Walter Burke Institute for Theoretical Physics thinks they have a new use for the novel technology – constraining the properties of dark matter.

Continue reading “Next Generation Gravitational Wave Detectors Could Pin Down Dark Matter”Early Black Holes Were Bigger Than We Thought

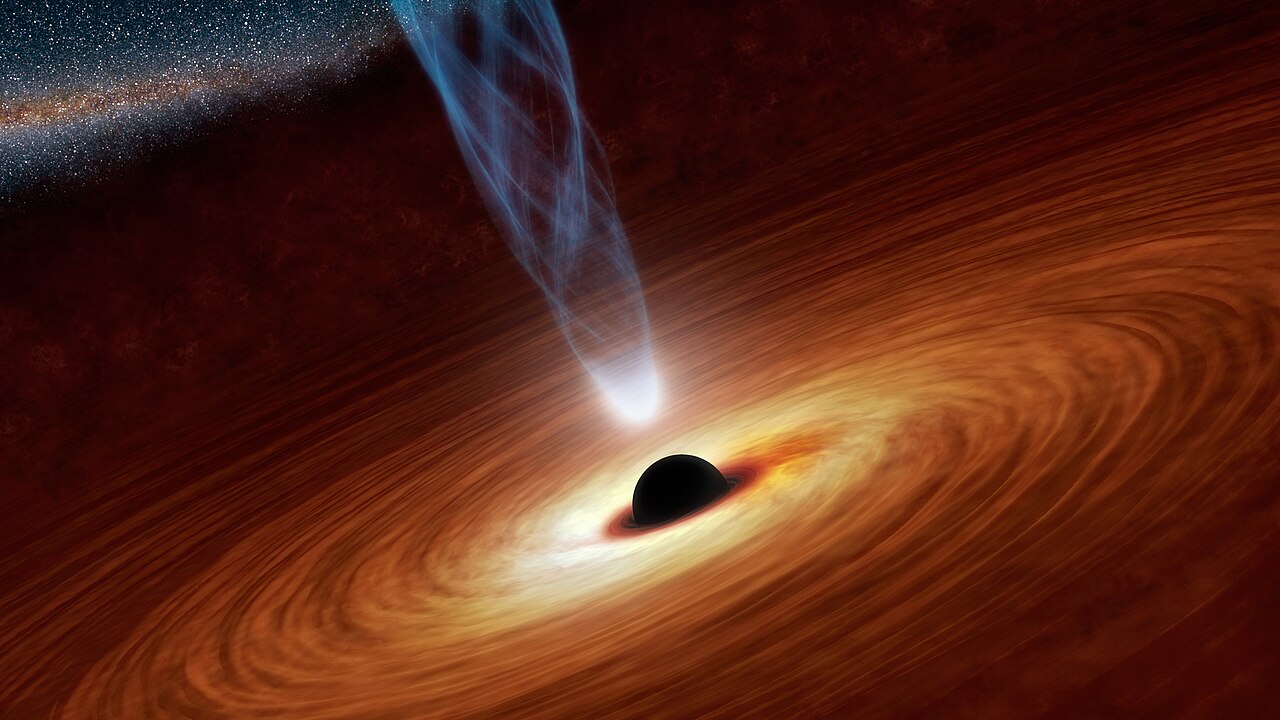

Every large galaxy in the nearby universe contains a supermassive black hole at its core. The mass of those black holes seems to have a relationship to the mass of the host galaxies themselves. But estimating the masses of more distant supermassive black holes is challenging. Astronomers extrapolate from what we know about nearby galaxies to estimate distant black hole masses, but it’s not a perfectly accurate measurement.

An astrophysicist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, Joseph Simon, recently proposed that there might be a better way to measure black hole mass, and his model indicates that early black holes may be much larger than other predictions suggest.

Continue reading “Early Black Holes Were Bigger Than We Thought”Astronomers Have Never Detected Merging Supermassive Black Holes. That Might Be About to Change

Gravitational wave astronomy currently can only detect powerful rapid events, such as the mergers of neutron stars or stellar mass black holes. We’ve been very successful in detecting the mergers of stellar mass black holes, but a long-term goal is to detect the mergers of supermassive black holes.

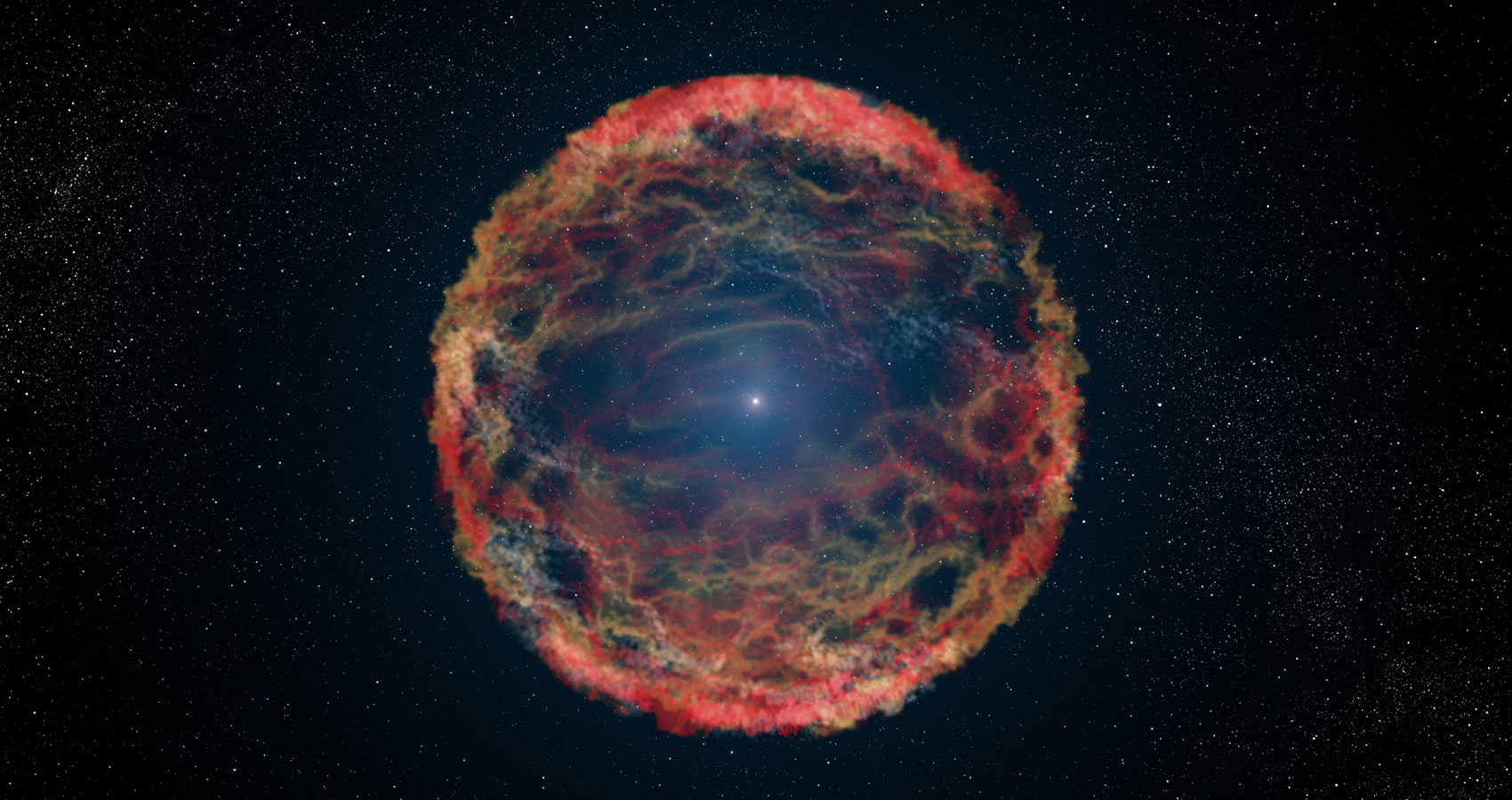

Continue reading “Astronomers Have Never Detected Merging Supermassive Black Holes. That Might Be About to Change”We Might Soon Detect the Gravitational Waves from Dying Stars

Researchers have discovered an exciting new source of gravitational waves. They are the remnants left over from a supernova explosion, and they may just reveal the secrets to how those explosions work.

Continue reading “We Might Soon Detect the Gravitational Waves from Dying Stars”When Black Holes Merge, They'll Ring Like a Bell

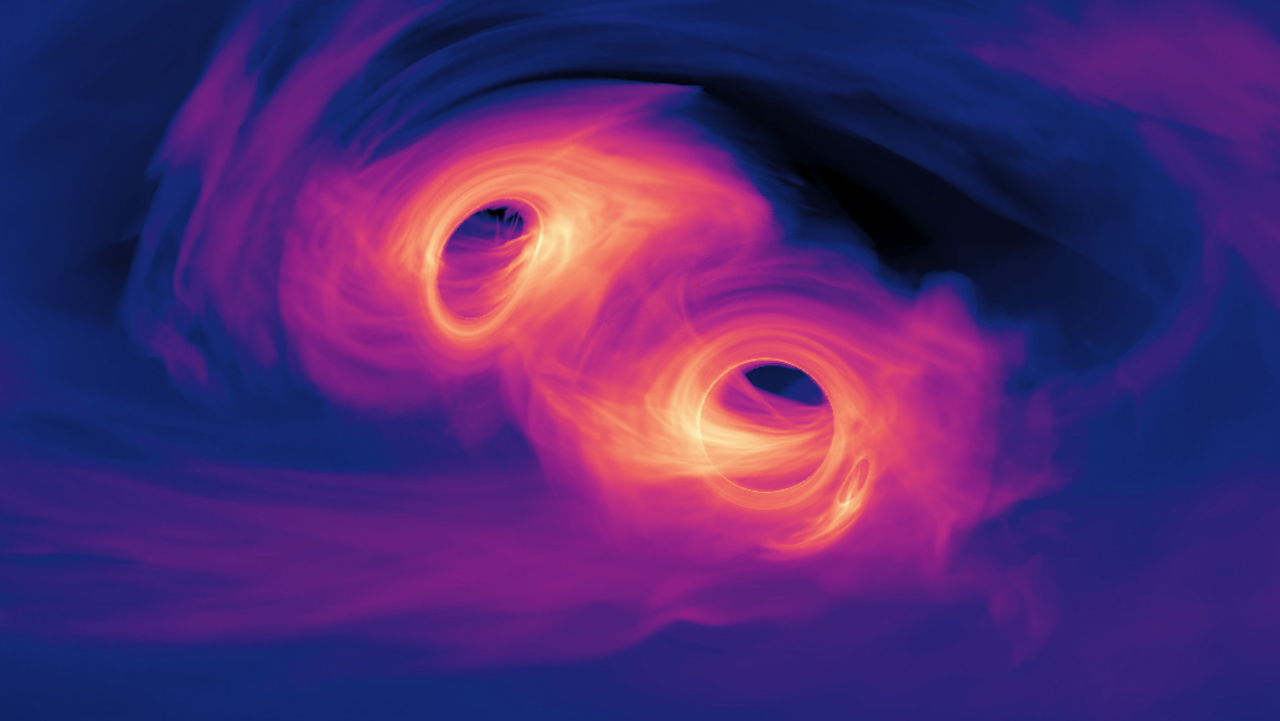

When two black holes collide, they don’t smash into each other the way two stars might. A black hole is an intensely curved region of space that can be described by only its mass, rotation, and electric charge, so two black holes release violent gravitational ripples as merge into a single black hole. The new black hole continues to emit gravitational waves until it settles down into a simple rotating black hole. That settling down period is known as the ring down, and its pattern holds clues to some of the deepest mysteries of gravitational physics.

Continue reading “When Black Holes Merge, They'll Ring Like a Bell”LISA Will Be a Remarkable Gravitational-Wave Observatory. But There’s a Way to Make it 100 Times More Powerful

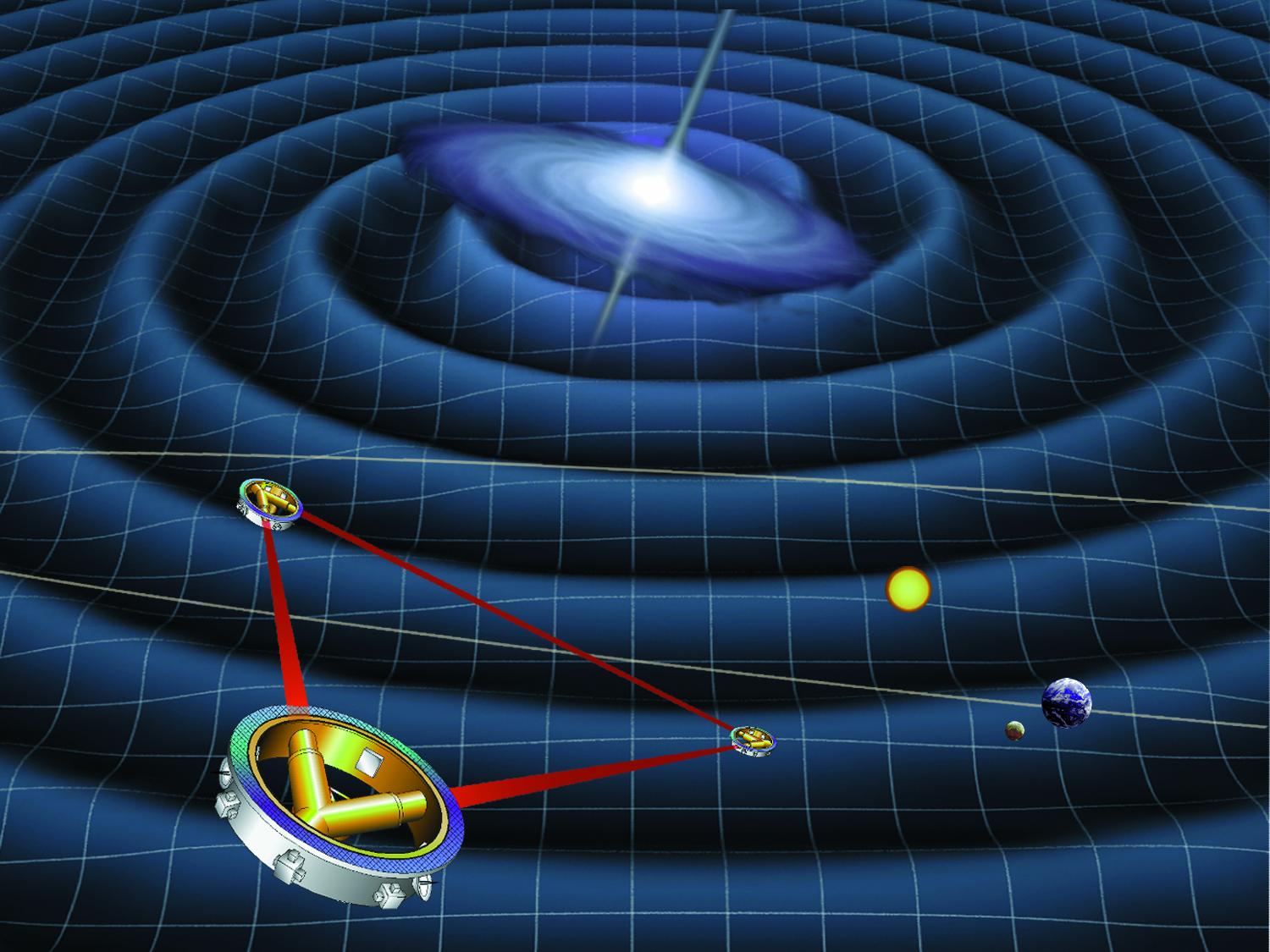

The first-time detection of Gravitational Waves (GW) by researchers at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) in 2015 triggered a revolution in astronomy. This phenomenon consists of ripples in spacetime caused by the merger of massive objects and was predicted a century prior by Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity. In the coming years, this burgeoning field will advance considerably thanks to the introduction of next-generation observatories, like the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA).

With greater sensitivity, astronomers will be able to trace GW events back to their source and use them to probe the interiors of exotic objects and the laws of physics. As part of their Voyage 2050 planning cycle, the European Space Agency (ESA) is considering mission themes that could be ready by 2050 – including GW astronomy. In a recent paper, researchers from the ESA’s Mission Analysis Section and the University of Glasgow presented a new concept that would build on LISA – known as LISAmax. As they report, this observatory could potentially improve GW sensitivity by two orders of magnitude.

Continue reading “LISA Will Be a Remarkable Gravitational-Wave Observatory. But There’s a Way to Make it 100 Times More Powerful”Gravitational Waves From Colliding Neutron Stars Matched to a Fast Radio Burst

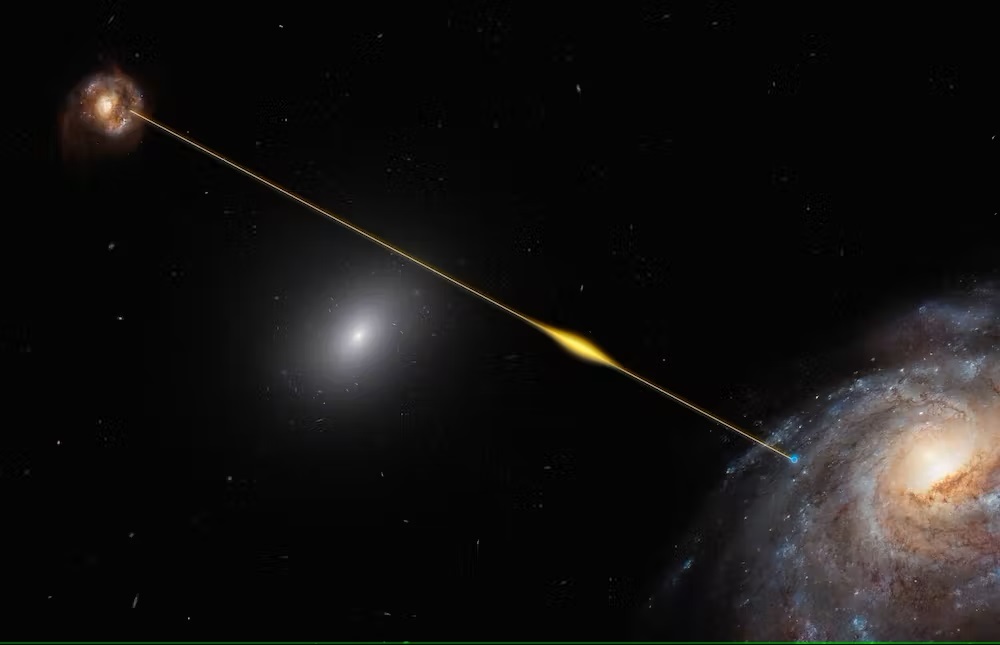

Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs) were first detected in 2007 (the Lorimer Burst) and have remained one of the most mysterious astronomical phenomena ever since. These bright radio pulses generally last a few milliseconds and are never heard from again (except in the rare case of Repeating FRBs). And then you have Gravitational Waves (GW), a phenomenon predicted by General Relativity that was first detected on September 14th, 2015. Together, these two phenomena have led to a revolution in astronomy where events are detected regularly and provide fresh insight into other cosmic mysteries.

In a new study led by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery (OzGrav), an Australian-American team of researchers has revealed that FRBs and GWs may be connected. According to their study, which recently appeared in the journal Nature Astronomy, the team noted a potential coincidence between a binary neutron star merger and a bright non-repeating FRB. If confirmed, their results could confirm what astronomers have expected for some time – that FRBs are caused by a variety of astronomical events.

Continue reading “Gravitational Waves From Colliding Neutron Stars Matched to a Fast Radio Burst”Gravitational Wave Observatories Could Search for Warp Drive Signatures

In 2016, scientists at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) announced that they had made the first confirmed detection of gravitational waves (GWs). This discovery confirmed a prediction made a century before by Einstein and his Theory of General Relativity and opened the door to a whole new field of astrophysical research. By studying the waves caused by the merger of massive objects, scientists could probe the interior of neutron stars, detect dark matter, and discover new particles around supermassive black holes (SMBHs).

According to new research led by the Advanced Propulsion Laboratory at Applied Physics (APL-AP), GWs could also be used in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). As they state in their paper, LIGO and other observatories (like Virgo and KAGRA) have the potential to look for GWs created by Rapid And/or Massive Accelerating spacecraft (RAMAcraft). By combining the power of these and next-generation observatories, we could create a RAMAcraft Detection And Ranging (RAMADAR) system that could probe all the stars in the Milky Way (100 to 200 billion) for signs of warp-drive-like signatures.

Continue reading “Gravitational Wave Observatories Could Search for Warp Drive Signatures”Shortly Before They Collided, two Black Holes Tangled Spacetime up Into Knots

In February 2016, scientists at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) announced the first-ever detection of gravitational waves (GWs). Originally predicted by Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, these waves are ripples in spacetime that occur whenever massive objects (like black holes and neutron stars) merge. Since then, countless GW events have been detected by observatories across the globe – to the point where they have become an almost daily occurrence. This has allowed astronomers to gain insight into some of the most extreme objects in the Universe.

In a recent study, an international team of researchers led by Cardiff University observed a binary black hole system originally detected in 2020 by the Advanced LIGO, Virgo, and Kamioki Gravitational Wave Observatory (KAGRA). In the process, the team noticed a peculiar twisting motion (aka. a precession) in the orbits of the two colliding black holes that was 10 billion times faster than what was noted with other precessing objects. This is the first time a precession has been observed with binary black holes, which confirms yet another phenomenon predicted by General Relativity (GR).

Continue reading “Shortly Before They Collided, two Black Holes Tangled Spacetime up Into Knots”Two Stars Orbiting Each Other Every 51 Minutes. This Can’t End Well

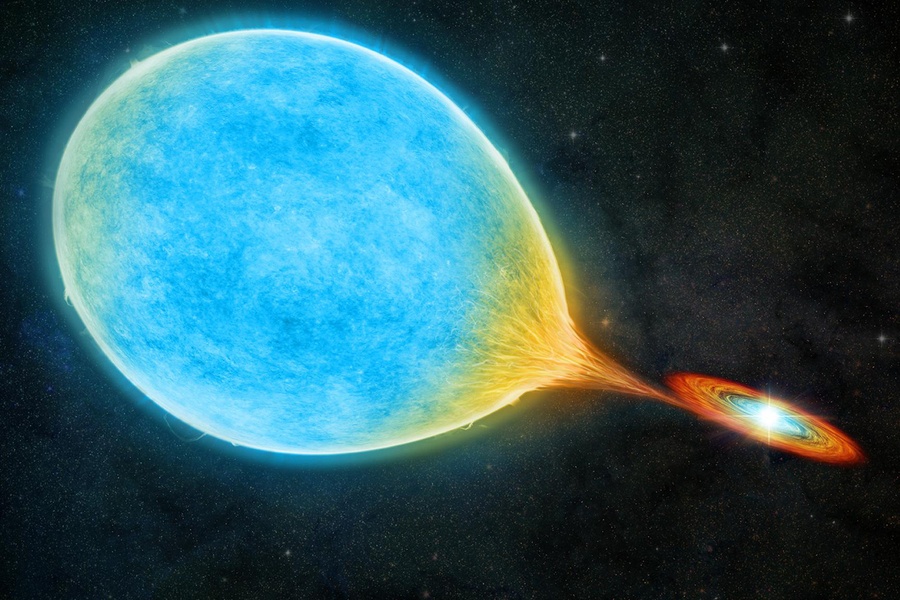

We don’t have to worry too much about our Sun. It can burn our skin, and it can emit potent doses of charged material—called Solar storms—that can damage electrical systems. But the Sun is alone up there, making things simpler and more predictable.

Other stars are locked in relationships with one another as binary pairs. A new study found a binary pair of stars that are so close to each other they orbit every 51 minutes, the shortest orbit ever seen in a binary system. Their proximity to one another spells trouble.

Continue reading “Two Stars Orbiting Each Other Every 51 Minutes. This Can’t End Well”