[/caption]

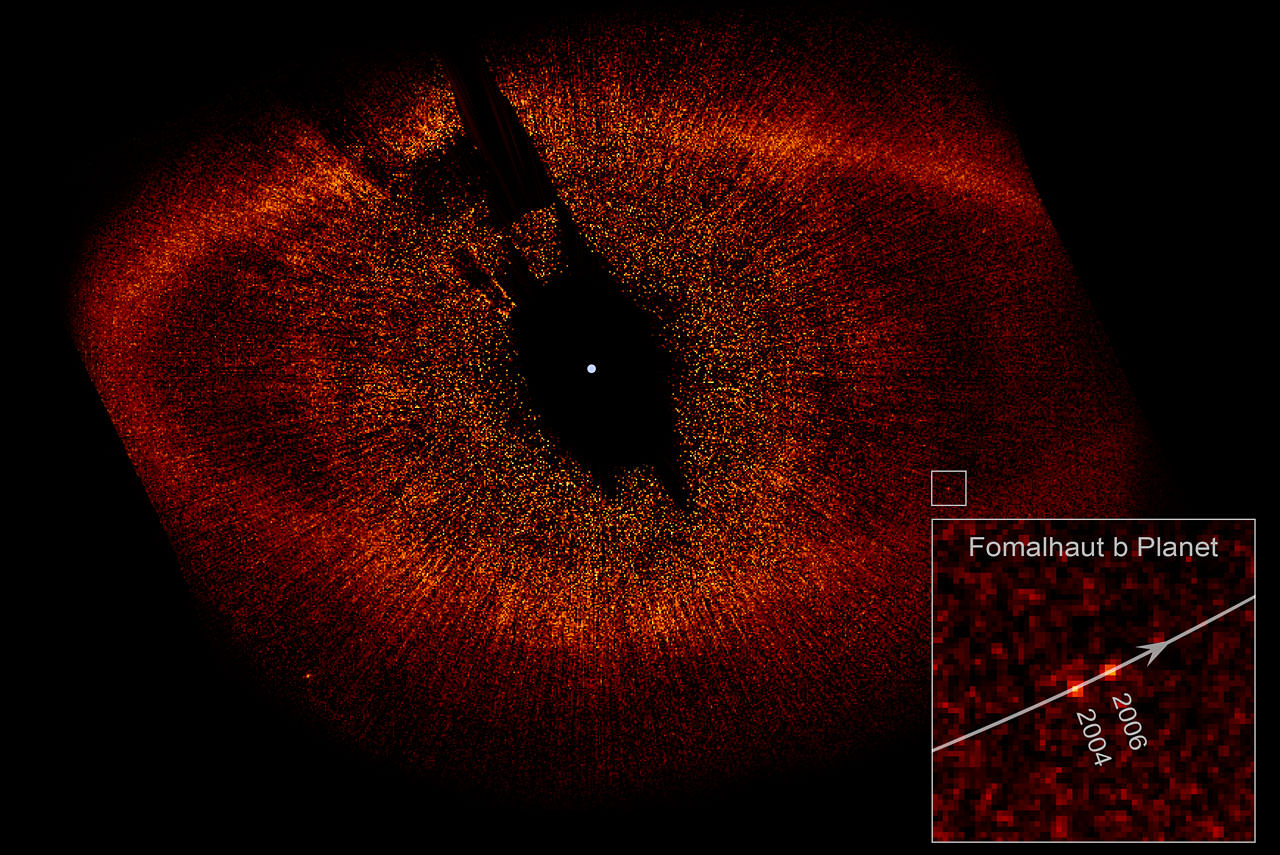

The planetary system of the star Fomalhaut has been one of intense debate over the past few years. In 2008, it was announced that a large, Saturn mass planet shepherd a large dust ring and was spotted in visual images from Hubble. But in late 2011 infrared observations called the previous detections into question. Now joining the discussion is the recently completed Atacama Large Millimeter/sub-millimeter Array (ALMA). This radio observatory suggests that there may be more planets than previously detected.

ALMA sits in the high Atacama desert in northern Chile. This dry location is ideal for linking together the 66 radio dishes (although only 15 were used in the new observations) to give unprecedented resolution. With this new set of eyes, astronomers from the University of Florida and Bryant Space Science Center were able to study the fine details in the dust ring. These details were then compared to various models of how rings should function in different conditions.

The dust ring has several characteristics that any explanation would have to reproduce. The first was that the ring is slightly oval shaped. It must be exceptionally thin and have a sharp cutoff both on the interior and exterior edges. If the previously claimed planet, Fomalhaut b, were the only one present, it could not account for the outer edge of the disk being sharply truncated as well as the inner edge. Another possibility is that the ring is simply newly formed as the result of a collision between two planets and has not yet had time to dissipate giving it the sharp appearance. However, the authors note that planets at such a distance from the parent star shouldn’t have high enough relative velocities to crush them so finely.

Since neither of these explanations are sufficient, the team proposes that there are two planets that shepherd the ring: One interior and one exterior to it. Within our own solar system, we see similar effects in Uranus’ ε ring which is constrained by the moons Cordelia and Ophelia. Similarly, Saturn’s F ring is shepherded by Prometheus and Pandora. By varying the mass of hypothetical planets in the models, the authors could create a ring similar to that seen around Fomalhaut. However, the best fit was created by a pair of planets that were less than three times the mass of the Earth which would mean that the proposed mass for Fomalhaut b was significantly too high, further casting doubt on its existence. Additionally, the proposed orbit of Fomalhaut bwas 10 AU off from the orbit of the hypothetical interior shepherd planet.

Ultimately, these two planets are only hypothetical. Detecting them in a more direct fashion will prove challenging. The fact that their orbits wouldn’t be very close to line of sight as well as their distance from the star would make radial velocity detection impossible. Given the low proposed mass and the distance, they would reflect too little light to be able to be directly observed with current telescopes.