[/caption]

Editor’s note – Bruce Dorminey is a science journalist and author of Distant Wanderers: The Search for Planets beyond the Solar System.

Planet hunter extraordinaire Geoff Marcy recently let his frustration surface about the current state of the search for other habitable solar systems. Despite the phenomenal planet-finding success of NASA’s Kepler mission, Marcy, an astronomer at the University of California at Berkeley, correctly pointed out that NASA budget cuts have severely hampered the hunt for extrasolar life.

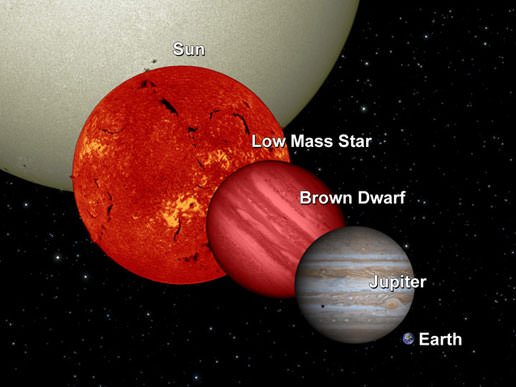

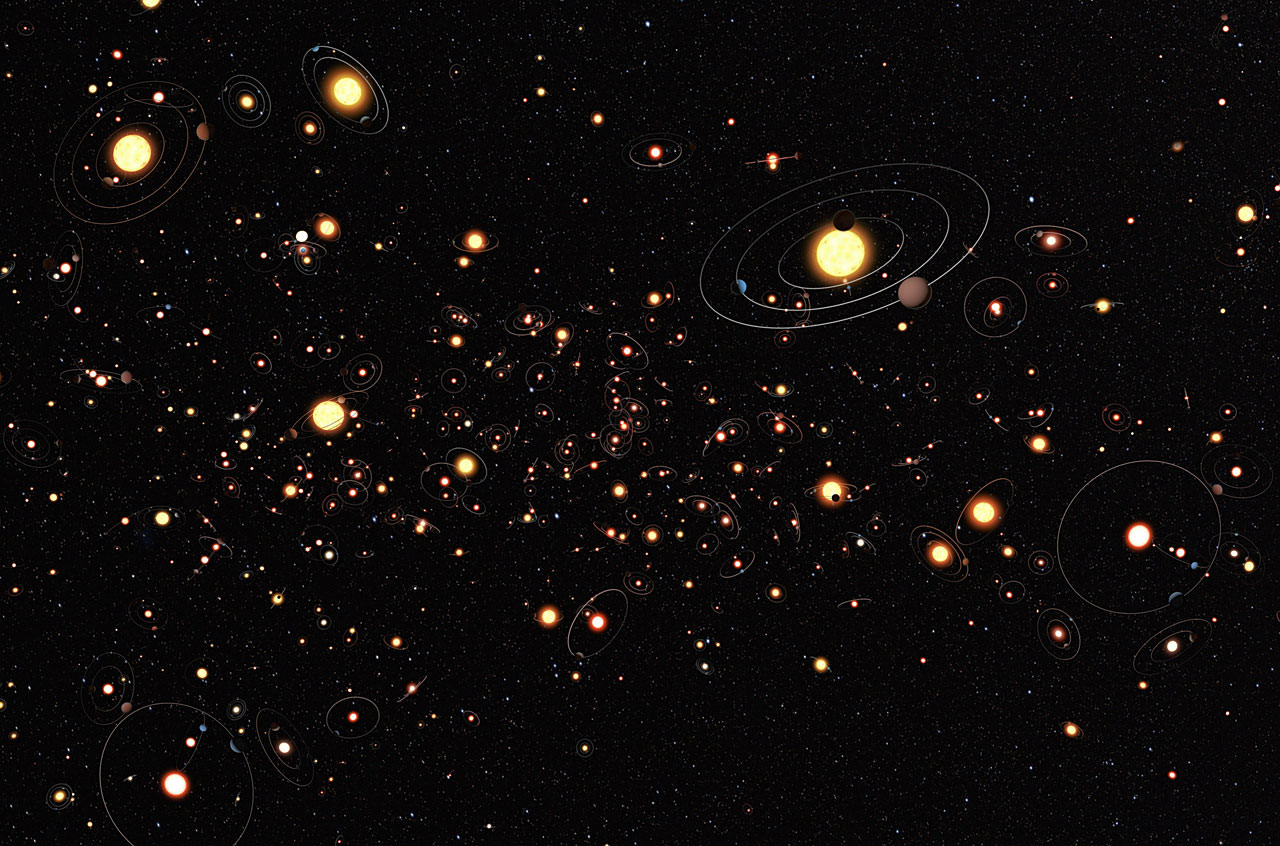

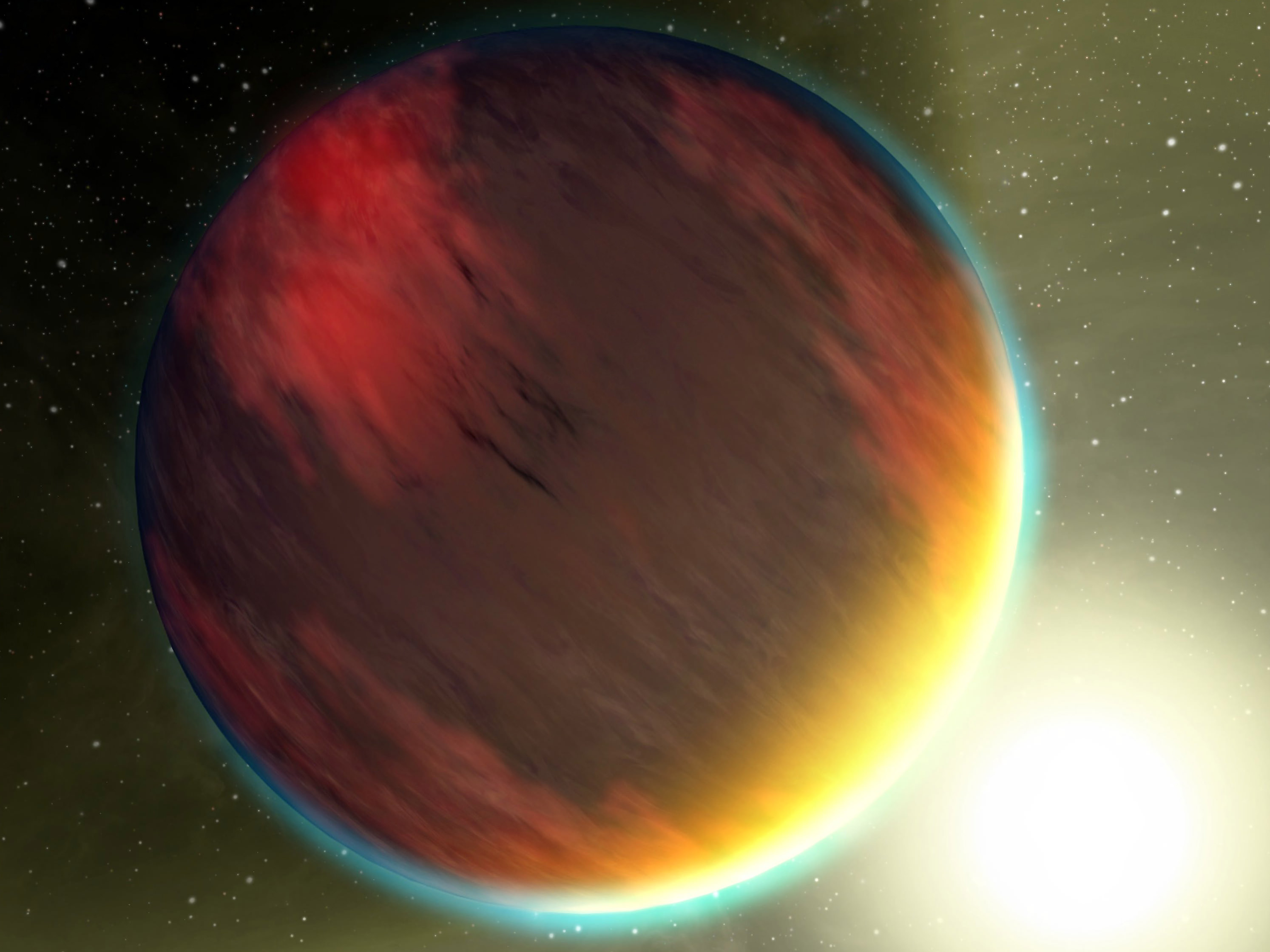

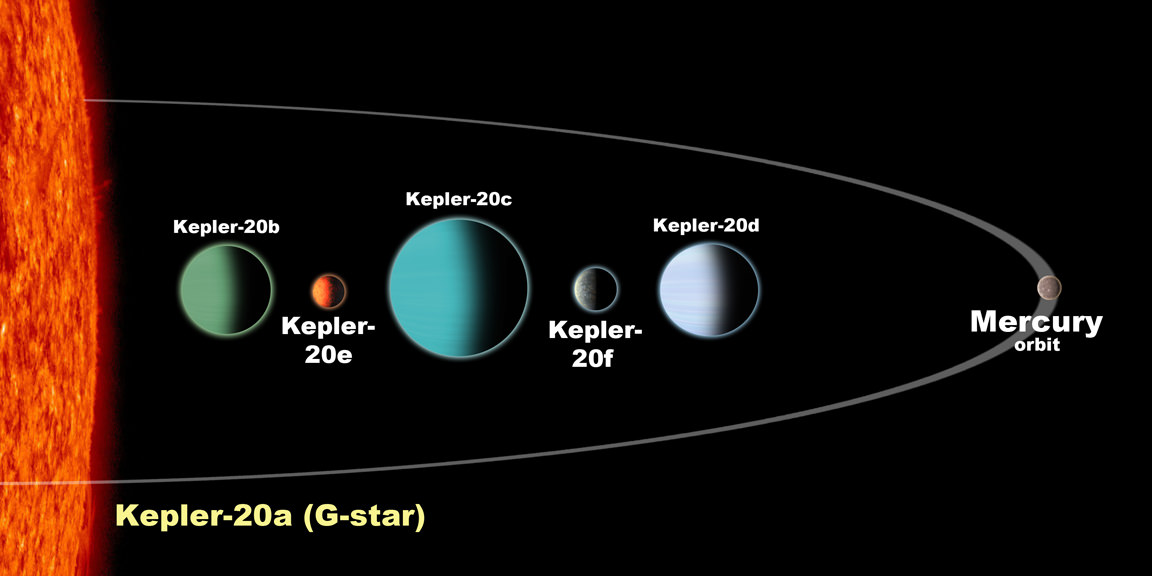

A decade ago, only a few dozen extrasolar planets had been detected. Today, by some recent gravitational microlensing estimates, there are more planets than stars in the Milky Way. But without the ability to characterize these extrasolar planetary atmospheres from space, we are astrobiologically hamstrung.

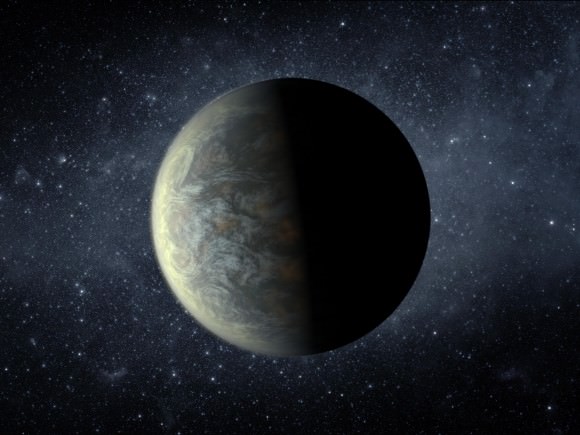

NASA’s goal had been that by 2020, we would have a pretty good idea about how frequently terrestrial Earth-mass planets orbit other stars — whether those planets have atmospheres that resemble our own; and, more crucially, whether those atmospheres exhibit the telltale signs of planets harboring life.

But consider how the federal government spends our tax dollars on a daily basis. Each and every day for more than a decade, the U.S. military spent roughly $1 billion a day funding congressionally-undeclared wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In contrast, NASA’s cancelled SIM and TPF missions were both originally estimated to have cost less than $1.5 billion dollars each.

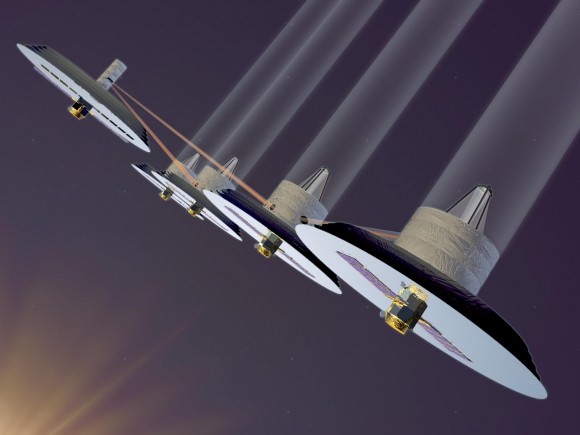

SIM, the Space Interferometry Mission, was to have focused on finding extrasolar earths in a targeted search; its follow-on mission, NASA’s TPF, the Terrestrial Planet Finder mission, was to have characterized the atmospheres of these earth twins in an attempt to remotely detect the signatures of life.

The astronomical community continues to be resourceful as it can in working around these problems. But if NASA had followed through with the SIM and TPF missions in the timeframe that it first announced, we would have a very good idea of our own earth’s galactic pecking order by now.

Instead, war-funding has taken priority. On the home front, we’ve let the attacks of 9/11 take us down a road that has resulted in our airports resembling Orwellian netherworlds. Most of us now accept that we must basically disrobe and be physically prodded before boarding an aircraft.

Kids born at the beginning of what was supposed to be a great new millennium — remember 2001: A Space Odyssey, anyone? — have instead grown up accustomed to running the gauntlet just to take their teddy bears onto the plane with them.

Contrast the country’s current poisoned national mood with the heady days of euphoria surrounding this country’s Moon shots.

Dare we attempt to again turn at least a portion of our swords back into ploughshares?

If the U.S. is going to continue to lead the world in science and technology, the country will have to quit living in a state of perpetual geopolitical paranoia and take space seriously again.

No one wants to turn a blind eye to our national defense and NASA may never return to its glory days. But something is amiss when within a generation, we’ve gone from John F. Kennedy pointedly challenging the nation to test its mettle by safely sending a man to the moon and back before the end of the decade to this current era of national teeth gnashing.

Newt Gingrich was openly ridiculed on the morning TV news shows for advocating that the U.S. use private enterprise to help us put a manned lunar colony on the moon. Mitt Romney responded that he’d fire any employee that walked into his office and suggested such a plan.

Perhaps Gingrich is not the ideal messenger for jumpstarting a long dormant manned lunar program. But our country has reached a sad nadir when a presidential candidate is publicly mocked for advocating the hard work of boldly revamping our national space policy.