Looking directly at stars is a bad way to find planets orbiting faraway suns but using a new technique, scientists can now sift the starlight to find new exoplanets millions of times dimmer than their parent stars.

“We are blinded by this starlight,” says Ben R. Oppenheimer, a curator in the American Museum of Natural History’s Department of Astrophysics and principal investigator for Project 1640. “Once we can actually see these exoplanets, we can determine the colors they emit, the chemical compositions of their atmospheres, and even the physical characteristics of their surfaces. Ultimately, direct measurements, when conducted from space, can be used to better understand the origin of Earth and to look for signs of life in other worlds.”

Using indirect detection methods, astronomers have found hundreds of planets orbiting other stars. The light stars emit, however, is tens of millions to billions of times brighter than the light reflected by planets.

Project 1640 is an advanced telescope imaging system, made up of the world’s most advanced adaptive optics system, instruments and software. The project operates at the 200-inch Hale Telescope at California’s Palomar Observatory. Engineers at the American Museum of Natural History, California Institute of Technology, and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory worked more than six years developing the new system.

Earth’s atmosphere wreaks havoc with starlight. The heating and cooling of the atmosphere produces turbulence that creates a twinkling effect on the point-like light from a star. Optics within a telescope also warp light. The instruments that make up Project 1640 manipulate starlight by deforming a mirror more than 7 million times a second to counteract the twinkling. This produces a crystal clear infrared image of the star with a precision smaller than one nanometer; about 100 times smaller than a typical bacteria.

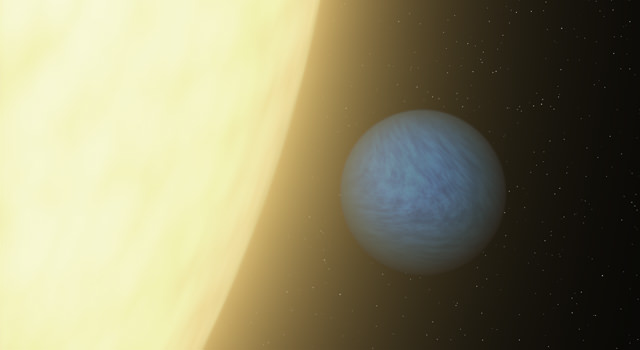

“Imaging planets directly is supremely challenging,” said Charles Beichman, executive director of the NASA ExoPlanet Science Institute at the California Institute of Technology. “Imagine trying to see a firefly whirling around a searchlight more than a thousand miles away.”

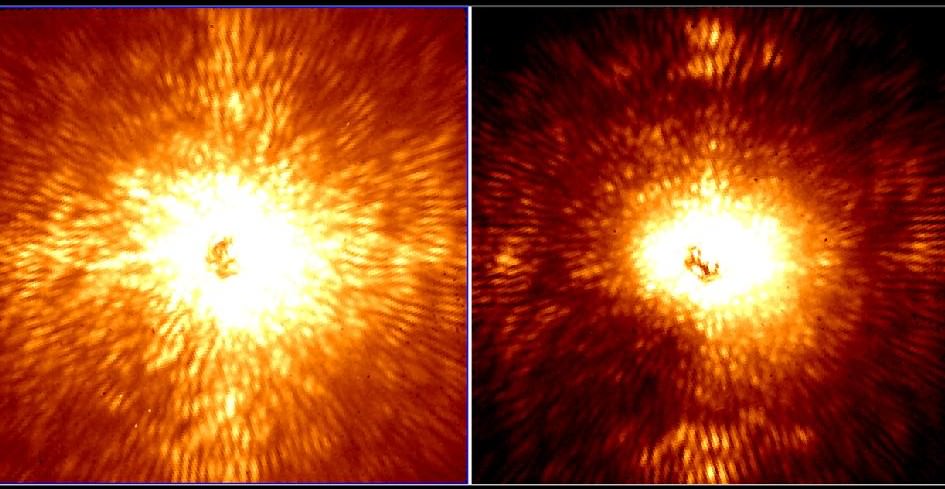

A coronagraph, built by the American Museum of Natural History, optically dims the star leaving other celestial objects in the field of view. Other instruments help create an “artificial eclipse” inside Project 1640. Only about half a percent of the original light remains in the form of a speckled background. These speckles can still be hundreds of times brighter than the dim planets. The instruments control the light from the speckles to further dim their brightness. What the instrument creates is a dark hole where the star had been while leaving the light reflected from any planets. Coordination of the system is extremely important, say the researchers. Even the smallest light leak would drown out the incredibly faint light from planets orbiting a star.

For now Project 1640, the world’s most advanced and highest contrast imaging system, is focusing on bright stars relatively close to Earth; about 200 light-years away. Their three-year survey includes plans to image hundreds of young stars. The planets they may find are likely to be very large, Jupiter-sized bodies.

“The more we learn about them, the more we realize how vastly different planetary systems can be from our own,” said Jet Propulsion Laboratory astronomer Gautam Vasisht. “All indications point to a tremendous diversity of planetary systems, far beyond what was imagined just 10 years ago. We are on the verge of an incredibly rich new field.”

Read more about Project 1640: http://research.amnh.org/astrophysics/research/project1640

Image Caption: Two images of HD 157728, a nearby star 1.5 times larger than the Sun. The star is centered in both images, and its light has been mostly removed by the adaptive optics system and coronagraph. The remaining starlight leaves a speckled background against which fainter objects cannot be seen. On the left, the image was made without the ultra-precise starlight control that Project 1640 is capable of. On the right, the wavefront sensor was active, and a darker square hole formed in the residual starlight, allowing objects up to 10 million times fainter than the star to be seen. Images were taken on June 14, 2012 with Project 1640 on the Palomar Observatory’s 200-inch Hale telescope. (Courtesy of Project 1640)