The Universe is a really, really big place. We’re talking… imperceptibly big! In fact, based on decades worth of observations, astronomers now believe that the observable Universe measures about 46 billion light years across. The key word there is observable, because when you take into account that which we cannot see, scientists think it’s actually more like 92 billion light years across.

The hardest part in all of this is making accurate measurements of the distances involved. But since the birth of modern astronomy, increasingly accurate methods have evolved. Aside from redshift and examining the light coming from distant stars and galaxies, astronomers also rely on a class of stars known as Cepheid Variables (CVs) to determine the distance of objects within and beyond our Galaxy.

Definition:

Variable stars are essentially stars that experience fluctuations in their brightness (aka. absolute luminosity). Cepheids Variables are special type of variable star in that they are hot and massive – five to twenty times as much mass as our Sun – and are known for their tendency to pulsate radially and vary in both diameter and temperature.

What’s more, these pulsations are directly related to their absolute luminosity, which occurs within well-defined and predictable time periods (ranging from 1 to 100 days). When plotted as a magnitude vs. period relationship, the shape of the Cephiad luminosity curve resembles that of a “shark fin” – do its sudden rise and peak, followed by a steadier decline.

The name is derived from Delta Cephei, a variable star in the Cepheus constellation that was the first CV to be identified. Analysis of this star’s spectrum suggests that CVs also undergo changes in terms of temperature (between 5500 – 66oo K) and diameter (~15%) during a pulsation period.

Use in Astronomy:

The relationship between the period of variability and the luminosity of CV stars makes them very useful in determining the distance of objects in our Universe. Once the period is measured, the luminosity can be determined, thus yielding accurate estimates of the star’s distance using distance modulus equation.

This equation states that: m – M = 5 log d – 5 – where m is the apparent magnitude of the object, M is the absolute magnitude of the object, and d is the distance to the object in parsecs. Cepheid variables can be seen and measured to a distance of about 20 million light years, compared to a maximum distance of about 65 light years for Earth-based parallax measurements and just over 326 light years for the ESA’s Hipparcos mission.

Because they are bright, and can be clearly seen million of light years away, they can be easily distinguished from other bright stars in their vicinity. Combined with the relationship between their variability and luminosity, this makes them highly useful tools in deducing the size and scale of our Universe.

Classes:

Cepheid variables are divided into two subclasses – Classical Cepheids and Type II Cepheids – based on differences in their masses, ages, and evolutionary histories. Classical Cepheids are Population I (metal-rich) variable stars that are 4-20 times more massive than the Sun and up to 100,000 times more luminous. They undergo pulsations with very regular periods on the order of days to months.

These Cepheids are typically yellow bright giants and supergiants (spectral class F6 – K2) and they experience radius changes in the millions of kilometers during a pulsation cycle. Classical Cepheids are used to determine distances to galaxies within the Local Group and beyond, and are a means by which the Hubble Constant can be established (see below).

Type II Cepheids are Population II (metal-poor) variable stars which pulsate with periods of typically between 1 and 50 days. Type II Cepheids are also older stars (~10 billion years) that have around half the mass of our Sun.

Type II Cepheids are also subdivided based on their period into the BL Her, W Virginis, and RV Tauri subclasses (named after specific examples) – which have periods of 1-4 days, 10-20 days, and more than 20 days, respectively. Type II Cepheids are used to establish the distance to the Galactic Center, globular clusters, and neighboring galaxies.

There are also those that do not fit into either category, which are known as Anomalous Cepheids. These variables have periods of less than 2 days (similar to RR Lyrae) but have higher luminosities. They also have higher masses than Type II Cepheids, and have unknown ages.

A small proportion of Cepheid variables have also been observed which pulsate in two modes at the same time, hence the name Double-mode Cepheids. A very small number pulsate in three modes, or an unusual combination of modes.

History of Observation:

The first Cepheid variable to be discovered was Eta Aquilae, which was observed on September 10th, 1784, by English astronomer Edward Pigott. Delta Cephei, for which this class of star is named, was discovered a few months later by amateur English astronomer John Goodricke.

In 1908, during an investigation of variable stars in the Magellanic Clouds, American astronomer Henrietta Swan Leavitt discovered the relationship between the period and luminosity of Classical Cepheids. After recording the periods of 25 different variables stars, she published her findings in 1912.

In the following years, several more astronomers would conduct research on Cepheids. By 1925, Edwin Hubble was able to establish the distance between the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy based on Cepheid variables within the latter. These findings were pivotal, in that they settled the Great Debate, where astronomers sought to established whether or not the Milky Way was unique, or one of many galaxies in the Universe.

By gauging the distance between the Milky Way and several other galaxies, and combining it with Vesto Slipher’s measurements of their redshift, Hubble and Milton L. Humason were able to formulate Hubble’s Law. In short, they were able to prove that the Universe is in a state of expansion, something that had been suggested years prior.

Further developments during the 20th century included dividing Cepheids into different classes, which helped resolve issues in determining astronomical distances. This was done largely by Walter Baade, who in the 1940s recognized the difference between Classical and Type II Cepheids based on their size, age and luminosities.

Limitations:

Despite their value in determining astronomical distances, there are some limitations with this method. Chief among them is the fact that with Type II Cepheids, the relationship between period and luminosity can be effected by their lower metallicity, photometric contamination, and the changing and unknown effect that gas and dust have on the light they emit (stellar extinction).

These unresolved issues have resulted in different values being cited for Hubble’s Constant – which range between 60 km/s per 1 million parsecs (Mpc) and 80 km/s/Mpc. Resolving this discrepancy is one of the largest problems in modern cosmology, since the true size and rate of expansion of the Universe are linked.

However, improvements in instrumentation and methodology are increasing the accuracy with which Cepheid Variables are observed. In time, it is hoped that observations of these curious and unique stars will yield truly accurate values, thus removing a key source of doubt about our understanding of the Universe.

We have written many interesting articles about Cepheid Variables here at Universe Today. Here’s Astronomers Find New Way to Measure Cosmic Distances, Astronomers Use Light Echo to Measure the Distance to a Star, and Astronomers Closing in on Dark Energy with Refined Hubble Constant.

Astronomy Cast has an interesting episode that explains the differences between Population I and II stars – Episode 75: Stellar Populations.

Sources:

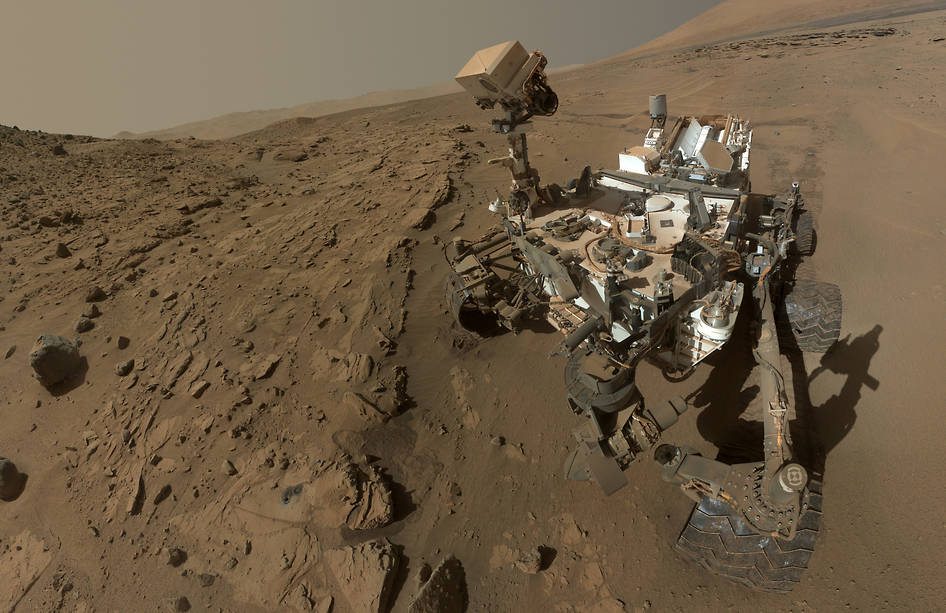

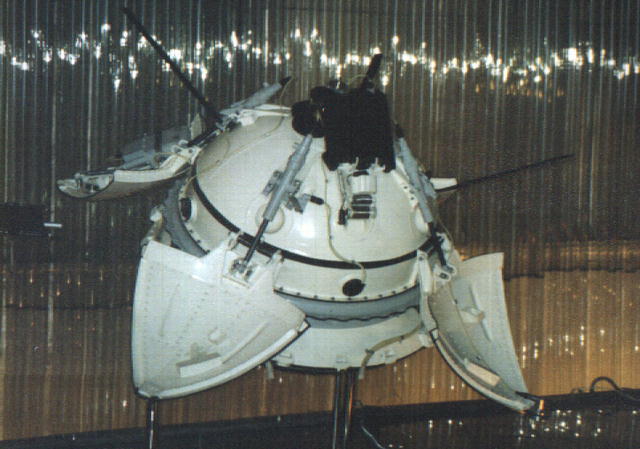

![The Viking 2 lander captured this image of itself on the Martian surface. By NASA - NASA website; description,[1] high resolution image.[2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17624](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/608px-Viking2lander1.jpg)