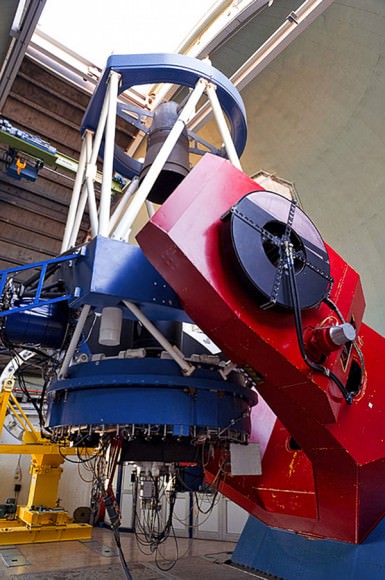

Almost all the planet hunting has been done from space. But there’s a new instrument installed on the European Southern Observatory’s 3.6 meter telescope called the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher which has already turned up 130 planets. Is this the future? Searching for planets from the ground?

Continue reading “Astronomy Cast Ep. 366: HARPS Spectrograph”

What Is This Empty Hole In Space?

What may appear at first glance to be an eerie, empty void in an otherwise star-filled scene is really a cloud of cold, dark dust and molecular gas, so dense and opaque that it obscures the distant stars that lie beyond it from our point of view.

Similar to the more well-known Barnard 68, “dark nebula” LDN 483 is seen above in an image taken by the MPG/ESO 2.2-meter telescope’s Wide Field Imager at the La Silla Observatory in Chile.

While it might seem like a cosmic no-man’s-land, no stars were harmed in the making of this image – on the contrary, dark nebulae like LDN 483 are veritable maternity wards for stars. As their cold gas and dust contracts and collapses new stars form inside them, remaining cool until they build up enough density and gravity to ignite fusion within their cores. Then, shining brightly, the young stars will gradually blast away the remaining material with their outpouring wind and radiation to reveal themselves to the galaxy.

The process may take several million years, but that’s just a brief flash in the age of the Universe. Until then, gestating stars within LDN 483 and many other clouds like it remain dim and hidden but keep growing strong.

Located fairly nearby, LDN 483 is about 700 light-years away from Earth in the constellation Serpens.

Source: ESO

VLTI Detects Exozodiacal Light Around Exoplanets

If you’ve ever stood outside after twilight has passed, or a few hours before the sun rises at dawn, then chances are you’ve witnessed the phenomenon known as zodiacal light. This effect, which looks like a faint, diffuse white glow in the night sky, is what happens when sunlight is reflected off of tiny particles and appears to extend up from the vicinity of the Sun. This reflected light is not just observed from Earth but can be observed from everywhere in the Solar System.

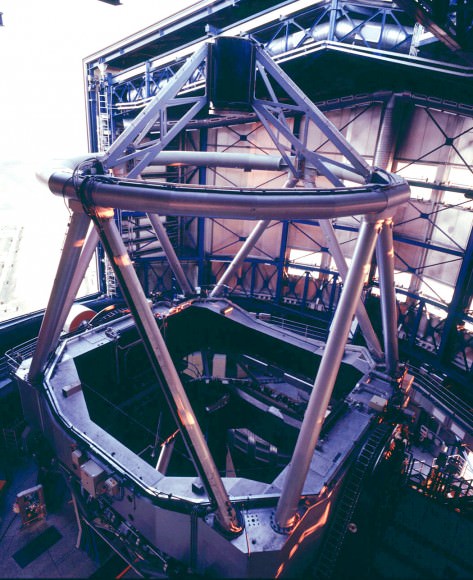

Using the full power of the Very Large Telescopic Interferometer (VLTI), an international team of astronomers recently discovered that the exozodiacal light – i.e., zodiacal light around other star systems – close to the habitable zones around nine nearby stars was far more extreme. The presence of such large amounts of dust in the inner regions around some stars may pose an obstacle to the direct imaging of Earth-like planets.

The reason for this is simple: even at low levels, exozodiacal dust causes light to become amplified intensely. For example, the light detected in this survey was roughly 1000 times brighter than the zodiacal light seen around the Sun. While this exozodiacal light had been previously detected, this is the first large systematic study of this phenomenon around nearby stars.

The team used the VLTI visitor instrument PIONIER which is able to interferometrically connect all four Auxiliary Telescopes or all four Unit Telescopes of the VLTI at the Paranal Observatory. This led to not only extremely high resolution of the targets but also allowed for a high observing efficiency.

Credit: ESO/G. Hüdepohl

In total, the team observed exozodiacal light from hot dust close to the habitable zones of 92 nearby stars and combined the new data with their earlier observations.

In contrast to these earlier observations – which were made with the Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA) array at Georgia State University – the team did not observe dust that will later form into planets, but dust created in collisions between small planets of a few kilometers in size – objects called planetesimals that are similar to the asteroids and comets of the Solar System. Dust of this kind is also the origin of the zodiacal light in the Solar System.

As a by-product, these observations have also led to the discovery of new, unexpected stellar companions orbiting around some of the most massive stars in the sample. “These new companions suggest that we should revise our current understanding of how many of this type of star are actually double,” says Lindsay Marion, lead author of an additional paper dedicated to this complementary work using the same data.

“If we want to study the evolution of Earth-like planets close to the habitable zone, we need to observe the zodiacal dust in this region around other stars,” said Steve Ertel, lead author of the paper, from ESO and the University of Grenoble in France. “Detecting and characterizing this kind of dust around other stars is a way to study the architecture and evolution of planetary systems.”

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Palomar Observatory.

However, the good news is that the number of stars containing zodiacal light at the level of our Solar System is most likely much higher than the numbers found in the survey.

“The high detection rate found at this bright level suggests that there must be a significant number of systems containing fainter dust, undetectable in our survey, but still much brighter than the Solar System’s zodiacal dust,” explains Olivier Absil, co-author of the paper, from the University of Liège. “The presence of such dust in so many systems could therefore become an obstacle for future observations, which aim to make direct images of Earth-like exoplanets.”

Therefore, these observations are only a first step towards more detailed studies of exozodiacal light, and need not dampen our spirits about discovering more Earth-like exoplanets in the near future.

Further Reading: ESO

Weekly Space Hangout – Sept. 26, 2014: So Wait, Do Black Holes Exist or Not?!?

Host: Fraser Cain (@fcain)

Guests:

Morgan Rehnberg (cosmicchatter.org / @cosmic_chatter)

Alessondra Springmann (@sondy)

Ramin Skibba (@raminskibba)

Brian Koberlein (@briankoberlein)

Jason Major (@JPMajor)

Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – Sept. 26, 2014: So Wait, Do Black Holes Exist or Not?!?”

ESO’s La Silla Observatory Reveals Beautiful Star Cluster “Laboratory”

Any human being knows the awe-inspiring wonder of a splash of stars against a dark backdrop. But it takes a skilled someone to truly appreciate a distant object viewed through an eyepiece. Your gut tightens as you realize that the tiny fuzzy blob is really thousands of light-years away.

That wave of amazement is encouraged by understanding and knowledge.

Stunning photographs of the cosmos further convey the beauty that arises from the simple interplay of dust, light and gas on absolutely massive and distant scales. The striking image above from ESO’s La Silla Observatory in Chile is but one example.

Stars are born in enormous clouds of gas and dust. Small pockets in these clouds collapse under the pull of gravity, eventually becoming so hot that they ignite nuclear fusion. The result is a cluster of tens to hundreds of thousands of stars bound together by their mutual gravitational attraction.

Every star in a cluster is roughly the same age and has the same chemical composition. They’re the closest thing astronomers have to a controlled laboratory environment.

The star cluster, NGC 3293, is located 8000 light-years from Earth in the constellation of Carina. It was first spotted by the French astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille during his stay in South Africa in 1751. Because it stands as one of the brightest clusters in the southern sky, de Lacaille was able to site it in a tiny telescope with an aperture of just 12 millimeters.

The cluster is less than 10 million years old, as can be seen by the abundance of hot, blue stars. Despite some evidence suggesting that there is still some ongoing star formation, it is thought that most, if not all, of the nearly 50 stars were born in one single event.

But even though these stars are all the same age, they do not all have the dazzling appearance of stars in their infancy. Some look positively elderly. The reason is simple: stars of different size, evolve at different speeds. More massive stars speed through their evolution, dying quickly, while less massive stars can live tens of billions of years.

Take the bright orange star at the bottom right of the cluster. Stars initially draw their energy from burning hydrogen into helium deep within their cores. But this star ran out of hydrogen fuel faster than its neighbors, and quickly evolved into a cool and bright, giant star with a contracted core but an extended atmosphere.

It’s now a cool, red giant, in a new stage of evolution, while its neighbors remain hot, young stars.

Eventually the star will collapse under its own gravity, throwing off its outer layers in a supernova explosion, and leaving behind a neutron star or a black hole. The peppering shock waves will likely initiate further star formation in the ever-changing laboratory.

Source: ESO

Dazzling New Views of a Familiar Cluster

Wow. It’s always amazing to get new views of familiar sky targets. And you always know that a “feast for the eyes” is in store when astronomers turn a world-class instrument towards a familiar celestial object.

Such an image was released this morning from the European Southern Observatory (ESO). Astronomers turned ESO’s 2.2-metre telescope towards Messier 7 in the constellation Scorpius recently, and gave us the star-studded view above.

Also known as NGC 6475, Messier 7 (M7) is an open cluster comprised of over 100 stars located about 800 light years distant. Located in the curved “stinger” of the Scorpion, M7 is a fine binocular object shining at a combined magnitude of about +3.3. M7 is physically about 25 light years across and appears about 80 arc minutes – almost the span of three Full Moons – in diameter from our Earthly vantage point.

One of the most prominent open clusters in the sky, M7 lies roughly in the direction of the galactic center in the nearby astronomical constellation of Sagittarius. When you’re looking towards M7 and the tail of Scorpius you’re looking just south of the galactic plane in the direction of the dusty core of our galaxy. The ESO image reveals the shining jewels of the cluster embedded against the more distant starry background.

Messier 7 is middle-aged as open clusters go, at 200 million years old. Of course, that’s still young for the individual stars themselves, which are just venturing out into the galaxy. The cluster will lose about 10% of its stellar population early on, as more massive stars live their lives fast and die young as supernovae. Our own solar system may have been witness to such nearby cataclysms as it left its unknown “birth cluster” early in its life.

Other stars in Messier 7 will eventually mature, “join the galactic car pool” in the main sequence as they disperse about the plane of the galaxy.

But beyond just providing a pretty picture, studying a cluster such as Messier 7 is crucial to our understanding stellar evolution. All of the stars in Messier 7 were “born” roughly around the same time, giving researchers a snapshot and a chance to contrast and compare how stars mature over there lives. Each open cluster also has a unique spectral “fingerprint,” a chemical marker that can even be used to identify the pedigree of a star.

For example, there’s controversy that the open cluster Messier 67 may actually be the birth place of our Sun. It is interesting to note that the spectra of stars in this cluster do bear a striking resemblance in terms of metallicity percentage to Sol. Remember, metals in astronomer-speak is any element beyond hydrogen and helium. A chief objection to the Messier 67 “birth-place hypothesis” is the high orbital inclination of the open cluster about the core of our galaxy: our Sun would have had to have undergone a series of improbable stellar encounters to have ended up its current sedate quarter of a billion year orbit about the Milky Way galaxy.

Still, this highlights the value of studying clusters such as Messier 6. It’s also interesting to note that there’s also data in what you can’t see in the above image – dark gaps are thought to be dust lanes and globules in the foreground. Though there is some thought that this dust is debris that may also be related to the cluster and may give us clues as to its overall rotation, its far more likely that these sorts of “dark spirals” related to the cluster have long since dispersed. M7 has completed about one full orbit about the Milky Way since its formation.

Another famous binocular object, the open cluster Messier 6 (M6) also known as the Butterfly Cluster lies nearby. Messier 7 also holds the distinction as being the southernmost object in Messier’s catalog. Compiled from Parisian latitudes, Charles Messier entirely missed southern wonders such as Omega Centauri in his collection of deep sky objects that were not to be mistaken for comets. We also always thought it curious that he included such obvious “non-comets” such as the Pleiades, but missed fine northern sky objects as the Double Cluster in the northern constellation Perseus.

Messier 7 is also sometimes called Ptolemy’s Cluster after astronomer Claudius Ptolemy, who first described it in 130 A.D. as the “nebula following the sting of Scorpius.” The season for hunting all of Messier’s objects in an all night marathon is coming right up in March, and Messier 7 is one of the last targets on the list, hanging high due south in the early morning sky.

Interested in catching how Messier 7 will evolve, or might look like up close? Check out Messier 45 (the Pleiades) and the V-shaped Hyades high in the skies in the constellation Taurus at dusk to see what’s in store as Messier 7 disperses, as well as the Ursa Major Moving Group.

And be sure to enjoy the fine view today of Messier 7 from the ESO!

Got pics of Messier 7 or any other deep sky objects? Send ’em, in to Universe Today!

Keeping An Eye On Gaia

Gaia, ESA’s long-anticipated mission to map the stars of our galaxy (as well as do a slew of other cool science things) is now tucked comfortably in its position in orbit around Earth-Moon L2, a gravitationally stable spot in space 1.5 million km (932,000 miles) away.

Once its mission begins in earnest, Gaia will watch about a billion stars an average of 70 times each over a five-year span… that’s 40 million observations every day. It will measure the position and key physical properties of each star, including its brightness, temperature and chemical composition, and help astronomers create the most detailed 3D map of the Milky Way ever.

But before Gaia can do this, its own position must be precisely determined. And so several of the world’s most high-powered telescopes are trained on Gaia, keeping track daily of exactly where it is up to an accuracy of 150 meters… which, with the ten-meter-wide spacecraft one and a half million kilometers away, isn’t too shabby.

Called GBOT, for Ground Based Orbit Tracking, the campaign to monitor Gaia’s position was first set up in 2008 — long before the mission launched. This allowed participating observatories to practice targeting on other existing spacecraft, like NASA’s WMAP and ESA’s Planck space telescopes.

The image above shows an image of Gaia (circled) as seen by the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope Survey Telescope (VST) atop Cerro Paranal in Chile, one of the supporting observatories in the GBOT campaign. The images were taken with the 2.6-meter Survey Telescope’s 268-megapixel OmegaCAM on Jan. 23, 6.5 minutes apart. With just the reflected sunlight off its circular sunshield, the distant spacecraft is about a million times fainter than what your eyes could see unaided.

It’s also one the closest objects ever imaged by the VST.

Currently Gaia is still undergoing calibration for its survey mission. Some problems have been encountered with stray sunlight reaching its detectors, and this may be due to the angle of the sunshield being a few degrees too high relative to the Sun. It could take a few weeks to implement an orientation correction; read more on the Gaia blog here.

Read more: Ghostly Cat’s Eye Nebula Shines In Space Telescope Calibration Image

Of the billion stars Gaia will observe, 99% have never had their distances accurately measured. Gaia will also observe 500,000 distant quasars, search for brown dwarfs and exoplanets, and will conduct experiments testing Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity. Find out more facts about the mission here.

Gaia launched on December 19, 2013, aboard a Soyuz VS06 from ESA’s spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. Watch the launch here.

Source: ESA

Astronomers Look “Inside” an Asteroid for the First Time

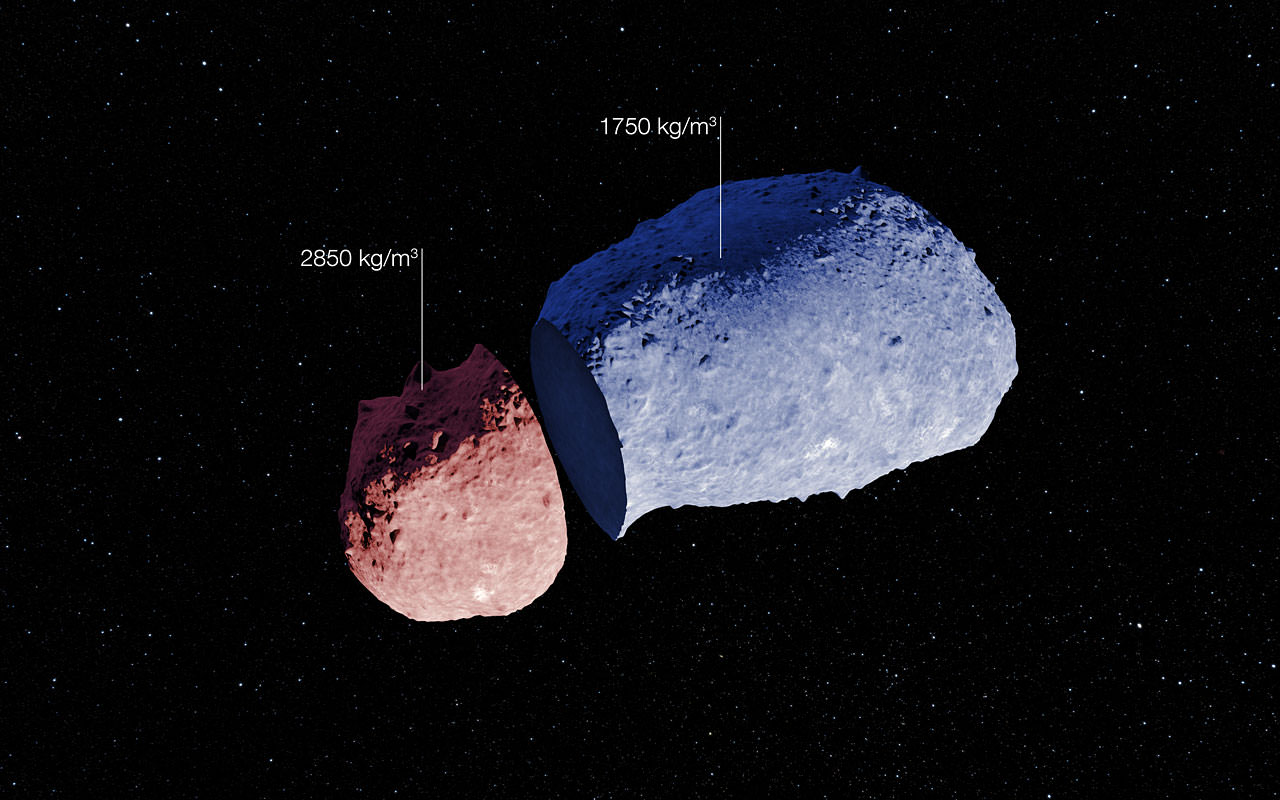

From directly inferring the inside of an asteroid for the first time, astronomers have discovered these space rocks can have strange variations in density. The observations of Itokawa — which you may remember from the Japanese Hayabusa mission that landed on the asteroid in 2005 — not only teach us more about how asteroids came to be, but could help protect Earth against stray space rocks in the future, the researchers said.

“This is the first time we have ever been able to to determine what it is like inside an asteroid,” stated Stephen Lowry, a University of Kent scientist who led the research. “We can see that Itokawa has a highly varied structure; this finding is a significant step forward in our understanding of rocky bodies in the solar system.”

It’s not clear why Itokawa has such different densities at opposite sides of its peanut shape; perhaps it was two asteroids that rubbed up against each other and merged. At just shy of six American football fields long, the space rock has density varying from 1.75 to 2.85 grams per cubic centimetre. This precise measurement came courtesy of the European Southern Observatory’s New Technology Telescope in Chile.

The telescope calculated the speed and speed changes of Itokawa’s spin and combined that information with data on how sunlight can affect the spin rate. Asteroids are generally tiny and irregularly shaped sorts of bodies, which means the effect of heat on the body is not evenly distributed. That small difference makes the asteroid’s spin rate change.

This heat effect (more properly called the Yarkovsky-O’Keefe-Radzievskii-Paddack effect) is slowly making Itokawa’s spin rate go faster, at a rate of 0.045 seconds every Earth year. This change, previously unexpected by scientists, is only possible if the peanut bulges have different densities, the scientists said.

“Finding that asteroids don’t have homogeneous interiors has far-reaching implications, particularly for models of binary asteroid formation,” added Lowry. “It could also help with work on reducing the danger of asteroid collisions with Earth, or with plans for future trips to these rocky bodies.”

More details on the research will be available in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Source: European Southern Observatory

Behind the Scenes: The “Making Of” the First Brown Dwarf Surface Map

By now, you will probably have heard that astronomers have produced the first global weather map for a brown dwarf. (If you haven’t, you can find the story here.) May be you’ve even built the cube model or the origami balloon model of the surface of the brown dwarf Luhman 16B the researchers provided (here).

Since one of my hats is that of public information officer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, where most of the map-making took place, I was involved in writing a press release about the result. But one aspect that I found particularly interesting didn’t get much coverage there. It’s that this particular bit of research is a good example of how fast-paced astronomy can be these days, and, more generally, it shows how astronomical research works. So here’s a behind-the-scenes look – a making-of, if you will – for the first brown dwarf surface map (see image on the right).

As in other sciences, if you want to be a successful astronomer, you need to do something new, and go beyond what’s been done before. That, after all, is what publishable new results are all about. Sometimes, such progress is driven by larger telescopes and more sensitive instruments becoming available. Sometimes, it’s about effort and patience, such as surveying a large number of objects and drawing conclusion from the data you’ve won.

Ingenuity plays a significant role. Think of the telescopes, instruments and analytical methods developed by astronomers as the tools in a constantly growing tool box. One way of obtaining new results is to combine these tools in new ways, or to apply them to new objects.

That’s why our opening scene is nothing special in astronomy: It shows Ian Crossfield, a post-doctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, and a number of colleagues (including institute director Thomas Henning) in early March 2013, discussing the possibility of applying one particular method of mapping stellar surfaces to a class of objects that had never been mapped in this way before.

The method is called Doppler imaging. It makes use of the fact that light from a rotating star is slightly shifted in frequency as the star rotates. As different parts of the stellar surfaces go by, whisked around by the star’s rotation, the frequency shifts vary slightly different depending on where the light-emitting region is located on the star. From these systematic variations, an approximate map of the stellar surface can be reconstructed, showing darker and brighter areas. Stars are much too distant for even the largest current telescopes to discern surface details, but in this way, a surface map can be reconstructed indirectly.

The method itself isn’t new. The basic concept was invented in the late 1950s, and the 1980s saw several applications to bright, slowly rotating stars, with astronomers using Doppler imaging to map those stars’ spots (dark patches on a stellar surface; the stellar analogue to Sun spots).

Crossfield and his colleagues were wondering: Could this method be applied to a brown dwarf – an intermediary between planet and star, more massive than a planet, but with insufficient mass for nuclear fusion to ignite in the object’s core, turning it into a star? Sadly, some quick calculations, taking into account what current telescopes and instruments can and cannot do as well as the properties of known brown dwarfs, showed that it wouldn’t work.

The available targets were too faint, and Doppler imaging needs lots of light: for one because you need to split the available light into the myriad colors of a spectrum, and also because you need to take many different rather short measurements – after all, you need to monitor how the subtle frequency shifts caused by the Doppler effect change over time.

So far, so ordinary. Most discussions of how to make observations of a completely new type probably come to the conclusion that it cannot be done – or cannot be done yet. But in this case, another driver of astronomical progress made an appearance: The discovery of new objects.

On March 11, Kevin Luhman, an astronomer at Penn State University, announced a momentous discovery: Using data from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), he had identified a system of two brown dwarfs orbiting each other. Remarkably, this system was at a distance of a mere 6.5 light-years from Earth. Only the Alpha Centauri star system and Barnard’s star are closer to Earth than that. In fact, Barnard’s star was the last time an object was discovered to be that close to our Solar system – and that discovery was made in 1916.

Modern astronomers are not known for coming up with snappy names, and the new object, which was designated WISE J104915.57-531906.1, was no exception. To be fair, this is not meant to be a real name; it’s a combination of the discovery instrument WISE with the system’s coordinates in the sky. Later, the alternative designation “Luhman 16AB” for the system was proposed, as this was the 16th binary system discovered by Kevin Luhman, with A and B denoting the binary system’s two components.

These days, the Internet gives the astronomical community immediate access to new discoveries as soon as they are announced. Many, probably most astronomers begin their working day by browsing recent submissions to astro-ph, the astrophysical section of the arXiv, an international repository of scientific papers. With a few exceptions – some journals insist on exclusive publication rights for at least a while –, this is where, in most cases, astronomers will get their first glimpse of their colleagues’ latest research papers.

Luhman posted his paper “Discovery of a Binary Brown Dwarf at 2 Parsecs from the Sun” on astro-ph on March 11. For Crossfield and his colleagues at MPIA, this was a game-changer. Suddenly, here was a brown dwarf for which Doppler imaging could conceivably work, and yield the first ever surface map of a brown dwarf.

However, it would still take the light-gathering power of one of the largest telescopes in the world to make this happen, and observation time on such telescopes is in high demand. Crossfield and his colleagues decided they needed to apply one more test before they would apply. Any object suitable for Doppler imaging will flicker ever so slightly, growing slightly brighter and darker in turn as brighter or darker surface areas rotate into view. Did Luhman 16A or 16B flicker – in astronomer-speak: did one of them, or perhaps both, show high variability?

Astronomy comes with its own time scales. Communication via the Internet is fast. But if you have a new idea, then ordinarily, you can’t just wait for night to fall and point your telescope accordingly. You need to get an observation proposal accepted, and this process takes time – typically between half a year and a year between your proposal and the actual observations. Also, applying is anything but a formality. Large facilities, like the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescopes, or space telescopes like the Hubble, typically receive applications for more than 5 times the amount of observing time that is actually available.

But there’s a short-cut – a way for particularly promising or time-critical observing projects to be completed much faster. It’s known as “Director’s Discretionary Time”, as the observatory director – or a deputy – are entitled to distribute this chunk of observing time at their discretion.

On April 2, Beth Biller, another MPIA post-doc (she is now at the University of Edinburgh), applied for Director’s Discretionary Time on the MPG/ESO 2.2 m telescope at ESO’s La Silla observatory in Chile. The proposal was approved the same day.

Biller’s proposal was to study Luhman 16A and 16B with an instrument called GROND. The instrument had been developed to study the afterglows of powerful, distant explosions known as gamma ray bursts. With ordinary astronomical objects, astronomers can take their time. These objects will not change much over the few hours an astronomer makes observations, first using one filter to capture one range of wavelengths (think “light of one color”), then another filter for another wavelength range. (Astronomical images usually capture one range of wavelengths – one color – at a time. If you look at a color image, it’s usually the result of a series of observations, one color filter at a time.)

Gamma ray bursts and other transient phenomena are different. Their properties can change on a time scale of minutes, leaving no time for consecutive observations. That is why GROND allows for simultaneous observations of seven different colors.

Biller had proposed to use GROND’s unique capability for recording brightness variations for Luhman 16A and 16B in seven different colors simultaneously – a kind of measurement that had never been done before at this scale. The most simultaneous information researchers had gotten from a brown dwarf had been at two different wavelengths (work by Esther Buenzli, then at the University of Arizona’s Steward Observatory, and colleagues). Biller was going for seven. As slightly different wavelength regimes contain information about gas at slightly different colors, such measurements promised insight into the layer structure of these brown dwarfs – with different temperatures corresponding to different atmospheric layers at different heights.

For Crossfield and his colleagues – Biller among them –, such a measurement of brightness variations should also show whether or not one of the brown dwarfs was a good candidate for Doppler imaging.

As it turned out, they didn’t even have to wait that long. A group of astronomers around Michaël Gillon had pointed the small robotic telescope TRAPPIST, designed for detecting exoplanets by the brightness variations they cause when passing between their host star and an observer on Earth, to Luhman 16AB. The same day that Biller had applied for observing time, and her application been approved, the TRAPPIST group published a paper “Fast-evolving weather for the coolest of our two new substellar neighbours”, charting brightness variations for Luhman 16B.

This news caught Crossfield thousands of miles from home. Some astronomical observations do not require astronomers to leave their cozy offices – the proposal is sent to staff astronomers at one of the large telescopes, who make the observations once the conditions are right and send the data back via Internet. But other types of observations do require astronomers to travel to whatever telescope is being used – to Chile, say, to or to Hawaii.

When the brightness variations for Luhman 16B were announced, Crossfield was observing in Hawaii. He and his colleagues realized right away that, given the new results, Luhman 16B had moved from being a possible candidate for the Doppler imaging technique to being a promising one. On the flight from Hawaii back to Frankfurt, Crossfield quickly wrote an urgent observing proposal for Director’s Discretionary Time on CRIRES, a spectrograph installed on one of the 8 meter Very Large Telescopes (VLT) at ESO’s Paranal observatory in Chile, submitting his application on April 5. Five days later, the proposal was accepted.

On May 5, the giant 8 meter mirror of Antu, one of the four Unit Telescopes of the Very Large Telescope, turned towards the Southern constellation Vela (the “Sail of the Ship”). The light it collected was funneled into CRIRES, a high-resolution infrared spectrograph that is cooled down to about -200 degrees Celsius (-330 Fahrenheit) for better sensitivity.

Three and two weeks earlier, respectively, Biller’s observations had yielded rich data about the variability of both the brown dwarfs in the intended seven different wavelength bands.

At this point, no more than two months had passed between the original idea and the observations. But paraphrasing Edison’s famous quip, observational astronomy is 1% observation and 99% evaluation, as the raw data are analyzed, corrected, compared with models and inferences made about the properties of the observed objects.

For Beth Biller’s multi-wavelength monitoring of brightness variations, this took about five months. In early September, Biller and 17 coauthors, Crossfield and numerous other MPIA colleagues among them, submitted their article to the Astrophysical Journal Letters (ApJL) after some revisions, it was accepted on October 17. From October 18 onward, the results were accessible online at astro-ph, and a month later they were published on the ApJL website.

In late September, Crossfield and his colleagues had finished their Doppler imaging analysis of the CRIRES data. Results of such an analysis are never 100% certain, but the astronomers had found the most probable structure of the surface of Luhman 16B: a pattern of brighter and darker spots; clouds made of iron and other minerals drifting on hydrogen gas.

As is usual in the field, the text they submitted to the journal Nature was sent out to a referee – a scientist, who remains anonymous, and who gives recommendations to the journal’s editors whether or not a particular article should be published. Most of the time, even for an article the referee thinks should be published, he or she has some recommendations for improvement. After some revisions, Nature accepted the Crossfield et al. article in late December 2013.

With Nature, you are only allowed to publish the final, revised version on astro-ph or similar servers no less than 6 month after the publication in the journal. So while a number of colleagues will have heard about the brown dwarf map on January 9 at a session at the 223rd Meeting of the American Astronomical Society, in Washington, D.C., for the wider astronomical community, the online publication, on January 29, 2014, will have been the first glimpse of this new result. And you can bet that, seeing the brown dwarf map, a number of them will have started thinking about what else one could do. Stay tuned for the next generation of results.

And there you have it: 10 months of astronomical research, from idea to publication, resulting in the first surface map of a brown dwarf (Crossfield et al.) and the first seven-wavelength-bands-study of brightness variations of two brown dwarfs (Biller et al.). Taken together, the studies provide fascinating image of complex weather patterns on an object somewhere between a planet and a star the beginning of a new era for brown dwarf study, and an important step towards another goal: detailed surface maps of giant gas planets around other stars.

On a more personal note, this was my first ever press release to be picked up by the Weather Channel.

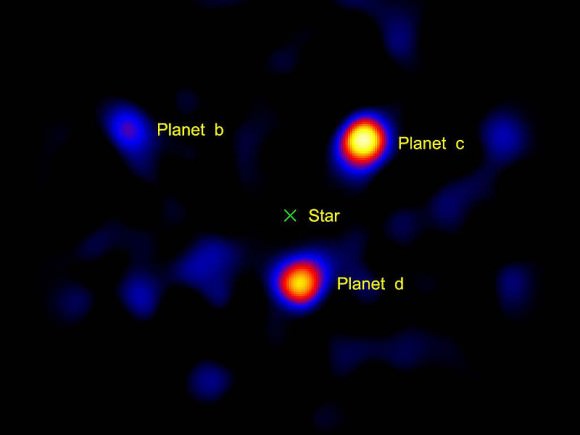

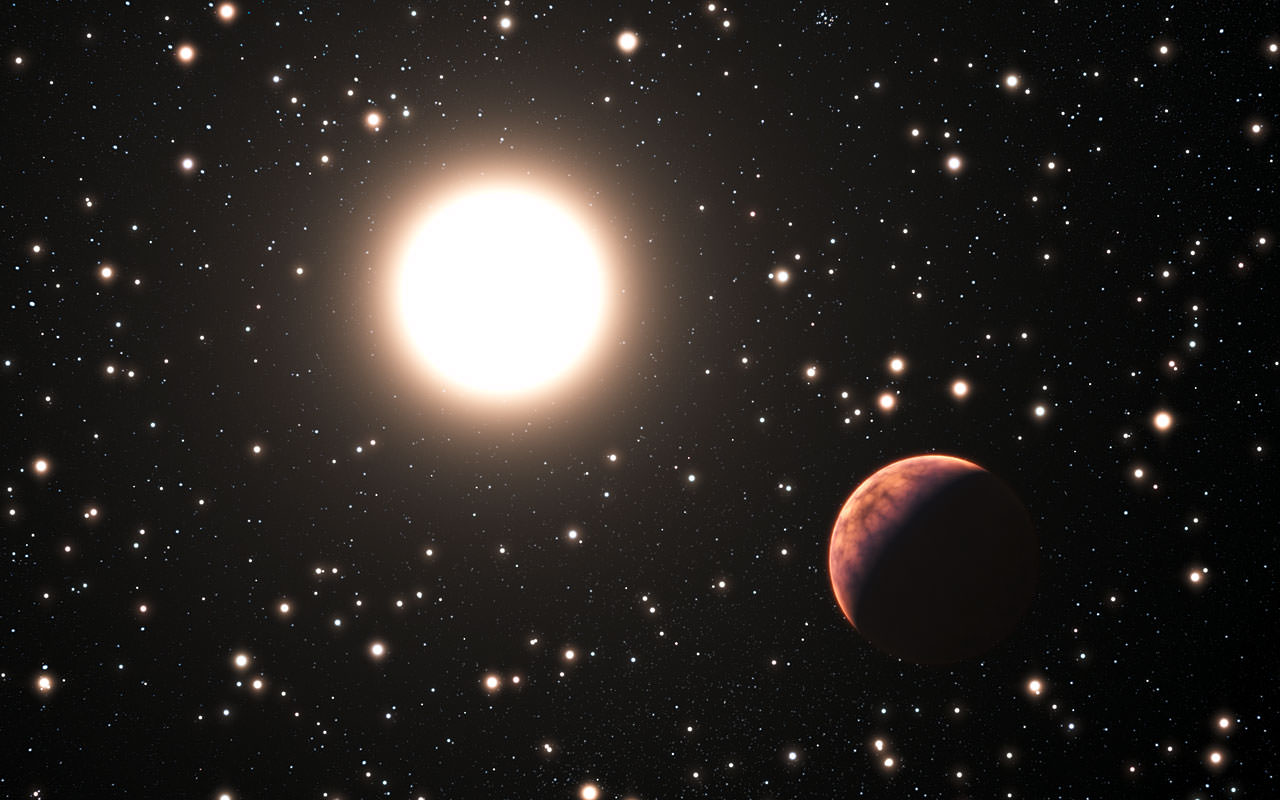

Three New Exoplanets Found In a Star Cluster

So far, just a handful of planets have been found orbiting stars in star clusters – and actually, astronomers weren’t too surprised about that. Star clusters can be pretty harsh places with hordes of stars huddling close together, with strong radiation and harsh stellar winds stripping planet-forming materials from the region.

But it turns out that perhaps astronomers are beginning to think differently about star clusters as being a homey place for exoplanets.

Scientists using several different telescopes, including the HARPS planet hunter in Chile have now discovered three planets orbiting stars in the cluster Messier 67.

“These new results show that planets in open star clusters are about as common as they are around isolated stars — but they are not easy to detect,” said Luca Pasquini from ESO, who is a co-author of a new paper about these planets. “The new results are in contrast to earlier work that failed to find cluster planets, but agrees with some other more recent observations. We are continuing to observe this cluster to find how stars with and without planets differ in mass and chemical makeup.”

The astronomers are pretty excited about one of these planets in particular, as it orbits a star that is a rare solar twin — a star that is almost identical to our Sun in all respects. This is the first “solar twin” in a cluster that has been found to have a planet.

“In the Messier 67 star cluster the stars are all about the same age and composition as the Sun,” said Anna Brucalassi from the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, Germany and lead author of the new paper on these planets. “This makes it a perfect laboratory to study how many planets form in such a crowded environment, and whether they form mostly around more massive or less massive stars.”

This cluster lies about 2,500 light-years away in the constellation of Cancer and contains about 500 stars. Many of the cluster stars are fainter than those normally targeted for exoplanet searches and trying to detect the weak signal from possible planets pushed HARPS to the limit, the team said.

They carefully monitored 88 selected stars in Messier 67 over a period of six years to look for the tiny telltale “wobbling” motions of the stars that reveal the presence of orbiting planets.

Three planets were discovered, two orbiting stars similar to the Sun and one orbiting a more massive and evolved red giant star. Two of the three planets are “hot Jupiters” — planets comparable to Jupiter in size, but much closer to their parent stars and therefore not in the habitable zone where liquid water could exist.

The first two planets both have about one third the mass of Jupiter and orbit their host stars in seven and five days respectively. The third planet takes 122 days to orbit its host and is more massive than Jupiter.

Star clusters come in two main types: open and globular. Open clusters are groups of stars that have formed together from a single cloud of gas and dust in the recent past, and are mainly found in the spiral arms of a galaxy like the Milky Way. Globular clusters are much bigger spherical collections of much older stars that orbit around the center of a galaxy. Despite careful searches, no planets have been found in a globular cluster and less than six in open clusters.

Another study last year from a team using the Kepler telescope found two planets in a dense open star cluster and the team stated that how planets can form in the hostile environments of dense star clusters is “not well understood, either observationally or theoretically.”

Exoplanets have been found in some amazing environments, and astronomers will continue to hunt for planets in these clusters of stars to try and learn more about how and why — and how many — exoplanets exist in star clusters.

ESOcast 62: Three planets found in star cluster from ESO Observatory on Vimeo.

Source: ESO