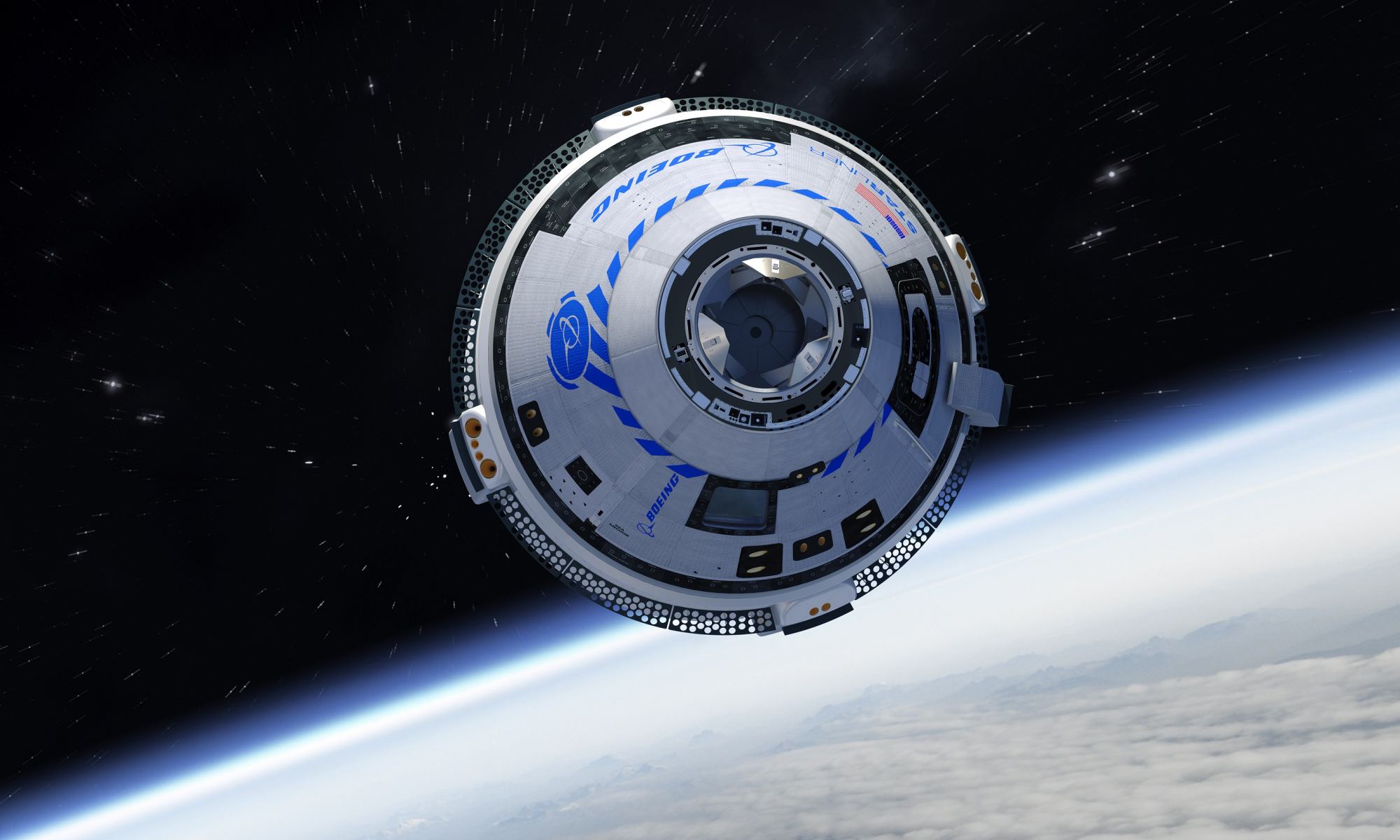

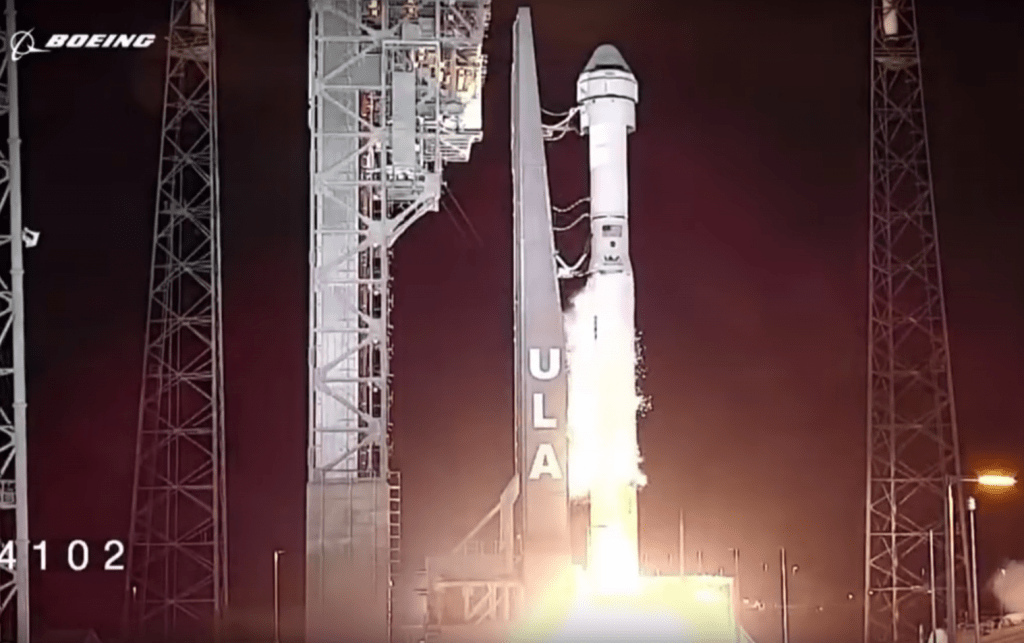

In 2014, NASA contracted two major aerospace companies (Boeing and SpaceX) to help them restore domestic launch capability to the United States. As part of the Commercial Crew Program (CCE), Boeing and SpaceX developed the CST-100 Starliner the Crew Dragon spacecraft, respectively. But whereas the Crew Dragon finished testing and even carried astronauts to the ISS, the Starliner met with some problems.

During its first uncrewed test flight – Orbital Flight Test-1 (OFT-1) – in December 2019, the Starliner experienced some failures that prevented it from docking with the ISS. After a thorough investigation, the joint NASA-Boeing Independent Review team has completed its final assessment and identified 80 areas where corrections need to be made before the Starliner can conduct another orbital flight test.

This latest review was concerned with the intermittent space-to-ground communication issue that contributed to the Calypso (the Starliner used for the OFT-1 demo) experiencing a sustained premature burn that used up most of its fuel. Two other issues, which were coding errors, had previously been investigated by the review team, which recommended that 61 corrective actions be taken by Boeing to address them.

As associate administrator Steve Jurczyk explained in a recent NASA press release:

“NASA and Boeing have completed a tremendous amount of work reviewing the issues experienced during the uncrewed flight test of Starliner. Ultimately, everything we’ve found will help us improve as we move forward in the development and testing of Starliner, and in our future work with commercial industry as a whole.”

With the completion of the investigation’s third and final focus area, Boeing and NASA are now executing action plans for each recommendation. The full list of corrective and preventive actions is proprietary, and therefore not available to the public. However, the 80 actions were divided into five categories, which Boeing and NASA has shared with the public.

For the first, Testing and Simulation, 21 recommendations were made, which included the need for greater hardware and software integration testing, the performance of an end-to-end test prior to each flight, reviewing subsystem behaviors and limitations, and addressing any identified simulation or emulation gaps.

The second category, Requirements, included 10 recommendations, which recommended an assessment of all software requirements with multiple logic conditions to ensure test coverage. Next up was the Process and Operational Improvements, which included 35 recommendations for software, test data, and safety review processes.

A further 7 recommendations were made in the Software category, which called for the updating of software code and a more robust antenna selection algorithm to correct the “elapsed timing error” that led to the Calypso’s premature engine burn, as well as the “Service Module Disposal Burn” anomaly that occurred during the crew and service module separation sequence.

Lastly, there were the 7 recommendations that fell into the Knowledge Capture and Hardware Modification. These included organizational changes to the safety reporting and Independent Validation and Verification (IV&V) approach, as well as the addition of an external Radio Frequency (RF) filter to prevent interference from satellites or other spacecraft in the vicinity.

Moving forward, the Independent Review Team has been asked to remain on board as Boeing and NASA execute their action plans. This past April, Boening indicated that once the corrective measures are complete, it will provide a second orbital test for free (which will including docking with the ISS) to demonstrate that the Starliner meets the needs of NASA and the CCP program. Said Jurczyk:

“As vital as it is to understand the technical causes that resulted in the flight test not fulfilling all of its planned objectives, it’s equally as important to understand how those causes connect to organizational factors that could be contributors. That’s why NASA also decided to perform a high visibility close call review that looked at our combined teams.”

In addition, NASA has completed its own “high-visibility close call” investigation into the test flight, which is required whenever a high-profile mission fails. This investigation reviewed the organizational factors within NASA and Boeing that may have contributed to the flight test anomalies and producing recommendations that would help avoid any future close calls.

Based on their findings, the team recommended that the NASA Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate incorporate a number of guidelines into future programs. These all came down to ensuring that NASA vets future contractors to ensure that their management and verification approaches meet the administration’s standards and that NASA’s and the contractor’s IV&V teams are on the same page.

Another important recommendation was for NASA to develop a best practices document for future programs so that they also implement the shared accountability model used by the CCP. Said Phil McAlister, director of commercial spaceflight development at NASA:

“I can’t stress enough how committed the Boeing team has been throughout this process. Boeing has worked collaboratively with NASA to perform these detailed assessments. To be clear, we have a lot more work ahead, but these significant steps help us move forward on the path toward resuming our flight tests.“

No indication has been given as to when Boeing and NASA will make their second attempt to launch the Starliner to orbit and dock with the ISS – aka. Orbital Flight Test-2 (OFT-2). But with both the joint independent review and high visibility close call investigation complete and the implementation of fixes already underway, it shouldn’t be long before the Starliner takes to space again!

The safety review process can be challenging and a bit of an ego-bruiser. But in the end, the verification process will ensure that Starliner is able to transport crews to and from space safely and effectively, providing NASA with domestic launch capability and ensuring its continued involvement with the ISS. Boeing is very close to that goal, and if future accidents can be prevented by some additional oversight, so much the better!

Further Reading: NASA