On December 11th, 2017, President Trump issued Space Policy Directive-1, a change in national space policy which tasked NASA with the creation of an innovative and sustainable program of exploration that would send astronauts back to the Moon. This was followed on March 26th, 2019, with President Trump directing NASA to land the first astronauts since the Apollo era on the lunar South Pole by 2024.

Named Project Artemis, after twin sister of Apollo and goddess of the Moon in Greek mythology, this project has expedited efforts to get NASA back to the Moon. However, with so much focus dedicated to getting back to the Moon, there are concerns that other projects being neglected – like the development of the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, a central part of creating a sustained human presence on the Moon and going on to Mars.

When SPD-1 was signed, several priorities were designated as being essential for return trips to the Moon. These included the continued development of the Space Launch System (SLS), the further development and testing of the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (MPCV), and between government agencies, private industry, and international partners.

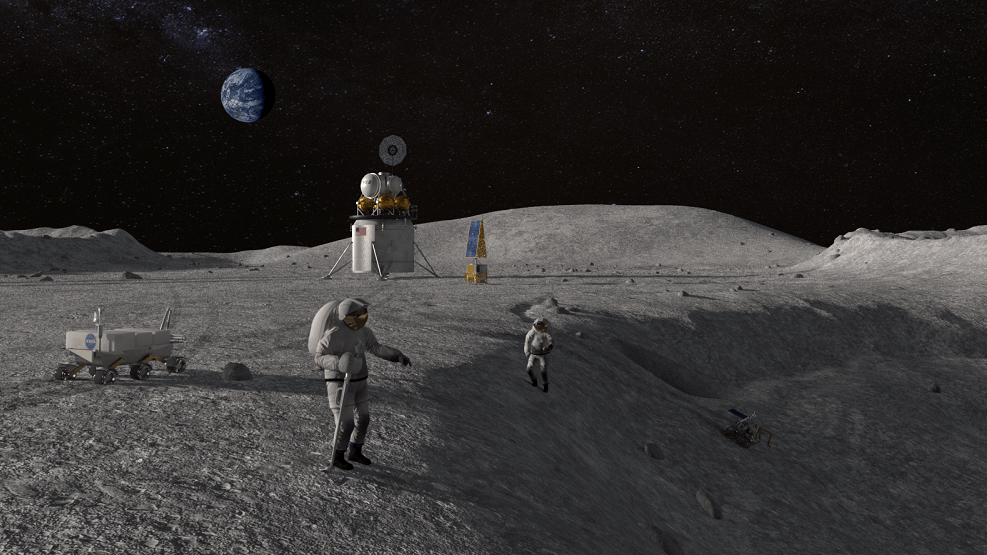

The ultimate goal of Artemis is to establish a sustainable human presence on the Moon by 2028, demonstrate new technologies, lay the foundation for private companies to build a lunar economy, and demonstrate Americas restored launch capability. The word sustainable is key and is in keeping with what NASA has been pursuing since the mid-2000s.

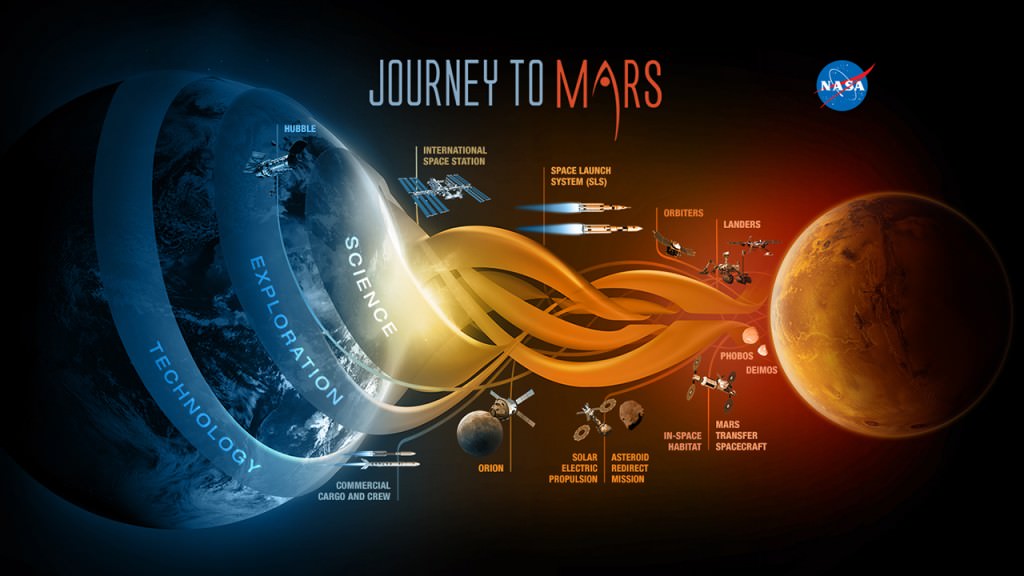

It was at this time that NASA began contemplating designing a new generation of heavy launch vehicles and spacecraft that would allow for renewed lunar exploration and an eventual mission to Mars. These efforts came together with the NASA Authorization Act of 2010, which green-lighted NASA’s proposed “Journey to Mars“.

Rather than going with a “Mars Direct” approach (as recommended by advocates like Robert Zubrin), NASA planned on following a “Moon to Mars” roadmap. It would begin with the development of the SLS and Orion here on Earth, what was known as Phase I: “Earth- Reliant”. The second phase, “Proving Grounds”, would involve the creation of infrastructure in cis-lunar space, like the Lunar Orbital-Platform Gateway (LOP-G).

The third phase, “Earth Independent”, is where missions to Mars would begin. Using the Lunar Gateway and a new spacecraft (the Deep Space Transport), NASA would build a station in orbit of Mars (the Mars Base Camp) that would allow for crewed missions to the surface using the reusable Mars Lander.

Phase I and II emphasized renewed missions to the Moon, which the Lunar Gateway would facilitate by providing an orbiting habitat for NASA (and other space agencies) as well as commercial partners. Despite the passage of SPD-1, which prioritized renewed lunar missions over the “Journey to Mars”, going back to the Moon was still viewed as a stepping stone to the crewed exploration of Mars.

The Gateway remained a priority as

“We want the Gateway to be a new place for human exploration and the world’s best science and technology… [T]he spaceship is important to expanding human presence deeper into the solar system, including to the Moon and Mars… Just like an airport here, spacecraft bound for the lunar surface or for Mars can use the Gateway to refuel or replace parts, and resupply things like food and oxygen without going home first.”

However, the announcement by VP Pence in March of this year that NASA was to land astronauts on the Moon by 2024 has had the effect of shaking up the agencies’ plans. Whether or not everything will be ready in time remains to be seen, and key parts of the mission architecture are already being scaled down to meet the new deadline.

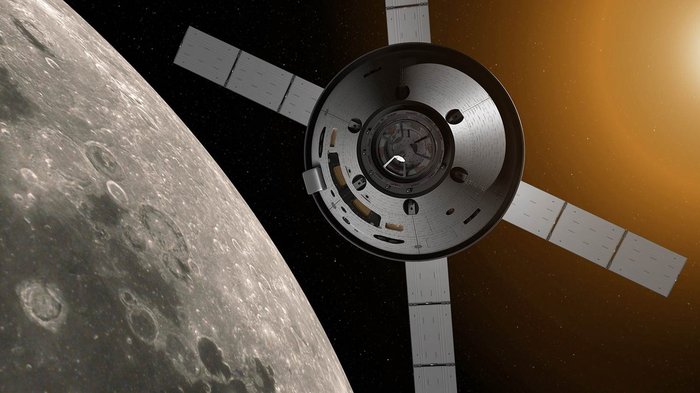

The Orion has already been flight tested with the Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1), which took place back in December of 2014. Its Abort Launch System (ALS) was tested for the second time with the Ascent Abort-2 (AA-2) test, which happened earlier this month. So while it should be ready for its planned uncrewed launch next year – Artemis 1, scheduled for July 2020 – it is unclear if the SLS will be ready by then.

As of June, NASA has reported that they and lead-contractor Boeing have managed to assemble four-fifths of the rocket’s massive core stage, and are two-thirds of the way towards joining the liquid hydrogen fuel tank to the upper part of the core stage. The next step is to complete outfitting the engine section and its the four RS-25 engines (leftover from the Space Shuttle era) before integrating it to the rest of the stage.

This will effectively complete the assembly of the nearly 58 meter-tall (190 foot) core stage. Beyond that, there is no telling if it will be ready to launch the spacecraft by 2021. Six more completed SLS’ will be needed to conduct the remaining missions that are part of

In addition, there has been pushback from the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) with regards to the continued funding of the Lunar Gateway. Apparently, it is the opinion of the budgeting office that a Gateway is not needed to send a crewed mission to the surface from lunar orbit.

As a senior NASA spaceflight source was quoted as saying to Ars Technica:

“OMB is definitely trying to kill Gateway. OMB looks at what the vice president said about getting to the Moon by 2024 and says you could do it cheaper if you didn’t have Gateway, and probably faster. They are fighting tooth and nail to nix the Gateway.”

Sacrificing the Lunar Gateway could have adverse effects on any planned “return to the Moon”. As NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine explained during a recent visit to the Johnson Space Center, the SLS and Orion are not like the hardware of the Apollo era and need some additional help to get crew to the lunar surface.

“We can get to low lunar orbit, but there’s not enough delta-V to leave low-lunar orbit,” he said. “So we can go, but you can’t come home. This is why we need to get more delta-V. Think of a small space station in orbit around the Moon where we can aggregate landing capability by the year 2024.”

In short, the current architecture for NASA’s “Moon to Mars” missions requires that there be a habitat in cis-lunar space that can allow for refueling and resupply operations, while also allowing crews to get to and from the lunar surface using a reusable lunar lander. This habitat will also ensure that other space agencies and commercial partners can begin work on the lunar surface that will allow for a sustainable human presence.

For instance, the European Space Agency has been saying for years how it intends to build an International Moon Village in the South Pole-Aitken Basin. This base would serve as a spiritual successor to the ISS, allowing for international teams to conduct vital research. It could also facilitate the creation of permanent lunar infrastructure like fuel processing sites, which would cut billions off the costs of deep-space missions.

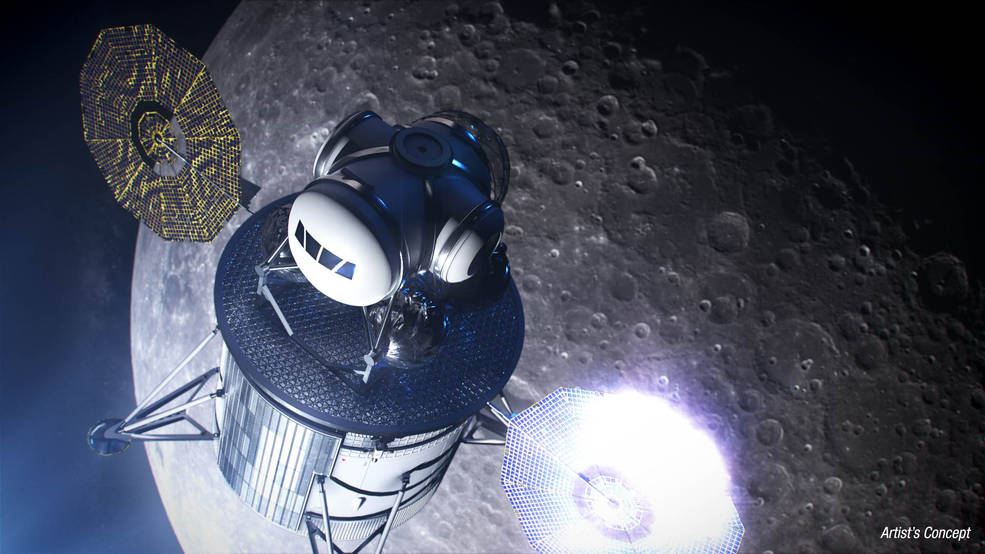

At present, there are no indications that the US government intends to cancel the Lunar Gateway. Back in May, NASA announced that it had contracted with Colorado-based aerospace company Maxar Technologies (formerly SSL) to develop and demonstrate the power and propulsion element of the Lunar Gateway.

This 50-kilowatt solar electric propulsion (SEP) spacecraft will serve as a mobile command and service module and a communications relay for human and robotic expeditions to the lunar surface. NASA aims to launch this element using a commercial rocket by late 2022. As Administrator Bridenstine said of this crucial component of the Gateway at the time:

“The power and propulsion element is the foundation of Gateway and a fine example of how partnerships with U.S. companies can help expedite NASA’s return to the Moon with the first woman and next man by 2024. It will be the key component upon which we will build our lunar Gateway outpost, the cornerstone of NASA’s sustainable and reusable Artemis exploration architecture on and around the Moon.”

It was also clear from VP Pence’s statement on March 26th, 2019, where he announced that NASA needed to send a crewed mission to the Moon within 5 years, that the Gateway was a key piece of the administration’s plans. Whereas the landing in 2024 would emphasize speed, the creation of the Gateway would parallel the Artemis missions and ensure long-term sustainability. As he said of the Gateway during his speech:

“Last year, NASA and American innovators began designing the precursor to outposts on the Moon and the mission to Mars, the Lunar Gateway. And we are rallying the world to join us in this vital work. This month, Canada became our first international partner and announced a 24-year commitment to cooperate on the Lunar Gateway. And, as we speak, we’re working with Congress to provide $500 million to get an American crew aboard this lunar-orbiting platform in the coming years.”

In the end, all of this reflects the attitude of uncertainty that has been prevalent since the turn of the century. With every change of administration, space exploration priorities and programs have had a tendency to be altered. However, the shifts that have taken place during the past few years have yielded their share of confusion and anxiety.

While the current administration announced that it was shifting focus to returning to the Moon in October of 2017, it appeared that the basic architecture for the “Journey to Mars” remained the same. The only change had been that Phase III was being deprioritized in order to focus on Phase I and Phase II.

At this juncture, it appears that the mission architecture could very well be subject to alterations in order to prioritize speed over sustainability. But in so doing, NASA could be repeating the very pattern it was hoping to avoid with the Apollo Program. Instead of simply going back to the Moon, the plan this time was to stay and then use that presence to set humanity’s sights on Mars.

But of course, its still 2019 and a lot can happen in the next five years. Only time will tell how this plays out.

Further Reading: ArsTechnica, NASA