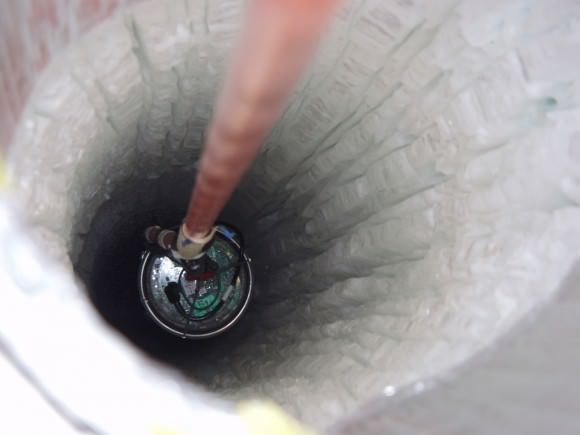

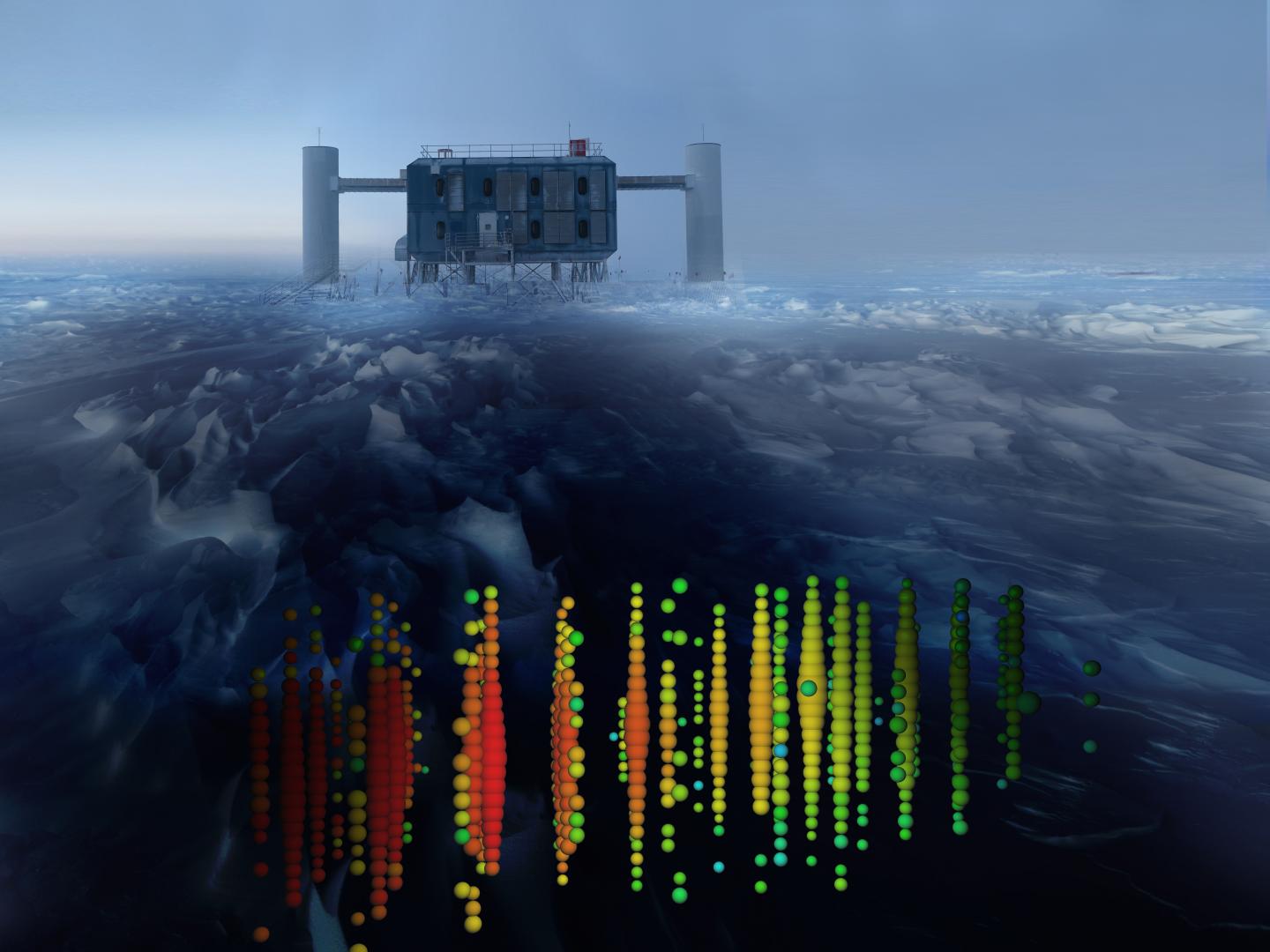

At the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica lies the IceCube Neutrino Observatory – a facility dedicated to the study of elementary particles known as neutrino. This array consists of 5,160 spherical optical sensors – Digital Optical Modules (DOMs) – buried within a cubic kilometer of clear ice. At present, this observatory is the largest neutrino detector in the world and has spent the past seven years studying how these particles behave and interact.

The most recent study released by the IceCube collaboration, with the assistance of physicists from Pennsylvania State University, has measured the Earth’s ability to block neutrinos for the first time. Consistent with the Standard Model of Particle Physics, they determined that while trillions of neutrinos pass through Earth (and us) on a regular basis, some are occasionally stopped by it.

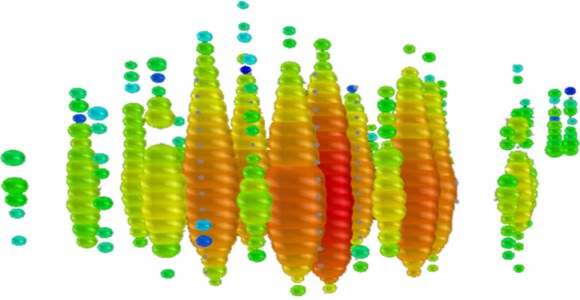

The study, titled “Measurement of the Multi-TeV Neutrino Interaction Cross-Section with IceCube Using Earth Absorption“, recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature. The study team’s results were based on the observation of 10,784 interactions made by high-energy, upward moving neutrinos, which were recorded over the course of a year at the observatory.

Back in 2013, the first detections of high-energy neutrinos were made by IceCube collaboration. These neutrinos – which were believed to be astrophysical in origin – were in the peta-electron volt range, making them the highest energy neutrinos discovered to date. IceCube searches for signs of these interactions by looking for Cherenkov radiation, which is produced after fast-moving charged particles are slowed down by interacting with normal matter.

By detecting neutrinos that interact with the clear ice, the IceCube instruments were able to estimate the energy and direction of travel of the neutrinos. Despite these detections, however, the mystery remained as to whether or not any kind of matter could stop a neutrino as it journeyed through space. In accordance with the Standard Model of Particle Physics, this is something that should happen on occasion.

After observing interactions at IceCube for a year, the science team found that the neutrinos that had to travel the farthest through Earth were less likely to reach the detector. As Doug Cowen, a professor of physics and astronomy/astrophysics at Penn State, explained in a Penn State press release:

“This achievement is important because it shows, for the first time, that very-high-energy neutrinos can be absorbed by something – in this case, the Earth. We knew that lower-energy neutrinos pass through just about anything, but although we had expected higher-energy neutrinos to be different, no previous experiments had been able to demonstrate convincingly that higher-energy neutrinos could be stopped by anything.”

The existence of neutrinos was first proposed in 1930 by theoretical physicist Wolfgang Pauli, who postulated their existence as a way of explaining beta decay in terms of the conservation of energy law. They are so-named because they are electrically neutral, and only interact with matter very weakly – i.e. through the weak subatomic force and gravity. Because of this, neutrinos pass through normal matter on a regular basis.

Whereas neutrinos are produced regularly by stars and nuclear reactors here on Earth, the first neutrinos were formed during the Big Bang. The study of their interaction with normal matter can therefore tell us much about how the Universe evolved over the course of billions of years. Many scientists anticipate that the study of neutrinos will indicate the existence of new physics, ones which go beyond the Standard Model.

Because of this, the science team was somewhat surprised (and perhaps disappointed) with their results. As Francis Halzen – the principal investigator for the IceCube Neutrino Observatory and a professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison – explained:

“Understanding how neutrinos interact is key to the operation of IceCube. We were of course hoping for some new physics to appear, but we unfortunately find that the Standard Model, as usual, withstands the test.

For the most part, the neutrinos selected for this study were more than one million times more energetic than those that are produced by our Sun or nuclear power plants. The analysis also included some that were astrophysical in nature – i.e. produced beyond Earth’s atmosphere – and may have been accelerated towards Earth by supermassive black holes (SMBHs).

Darren Grant, a professor of physics at the University of Alberta, is also the spokesperson for the IceCube Collaboration. As he indicated, this latest interaction study opens doors for future neutrino research. “Neutrinos have quite a well-earned reputation of surprising us with their behavior,” he said. “It is incredibly exciting to see this first measurement and the potential it holds for future precision tests.”

This study not only provided the first measurement of the Earth’s absorption of neutrinos, it also offers opportunities for geophysical researchers who are hoping to use neutrinos to explore Earth’s interior. Given that Earth is capable of stopping some of the billions of high-energy particles that routinely pass through it, scientists could develop a method for studying the Earth’s inner and outer core, placing more accurate constraints on their sizes and densities.

It also shows that the IceCube Observatory is capable of reaching beyond its original purpose, which was particle physics research and the study of neutrinos. As this latest study clearly shows, it is capable of contributing to planetary science research and nuclear physics as well. Physicists also hope to use the full 86-string IceCube array to conduct a multi-year analysis, examining even higher ranges of neutrino energies.

As James Whitmore – the program director in the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) physics division (which provides support for IceCube) – indicated, this could allow them to truly search for physics that go beyond the Standard Model.

“IceCube was built to both explore the frontiers of physics and, in doing so, possibly challenge existing perceptions of the nature of universe. This new finding and others yet to come are in that spirit of scientific discovery.”

Ever since the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012, physicists have been secure in the knowledge that the long journey to confirm the Standard Model was now complete. Since then, they have set their sets farther, hoping to find new physics that could resolve some of the deeper mysteries of the Universe – i.e. supersymmetry, a Theory of Everything (ToE), etc.

This, as well as studying how physics work at the highest energy levels (similar to those that existed during the Big Bang) is the current preoccupation of physicists. If they are successful, we might just come to understand how this massive thing known as the Universe works.

Further Reading: Penn State, Nature

I wonder if ice is better at absorbing things than rock/iron… perhaps a source to explain alittle extra heat in those icey moons.