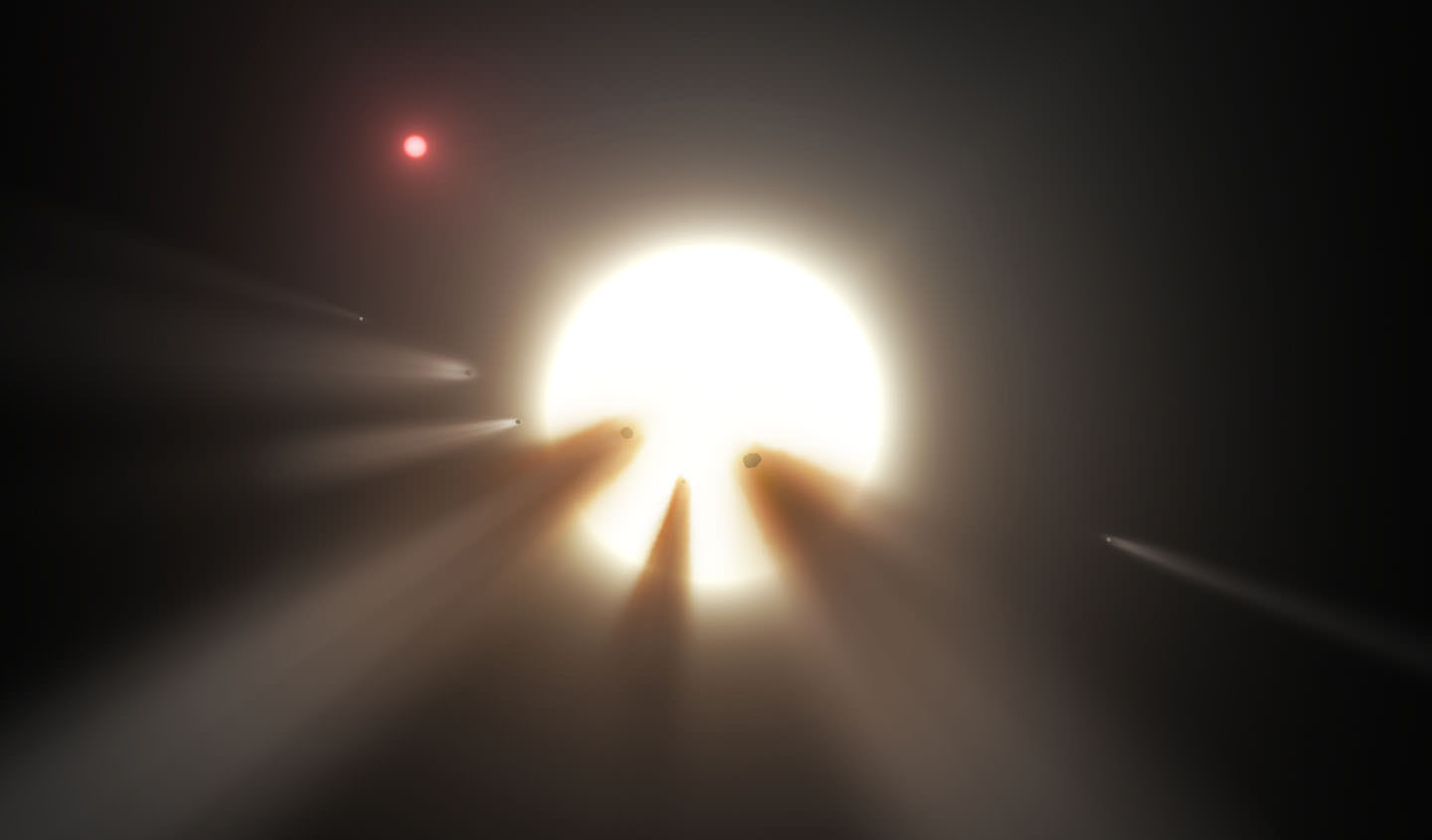

The story of KIC 8462852 appears far from over. You’ll recall NASA’s Kepler mission had monitored the star for four years, observing two unusual incidents, in 2011 and 2013, when its light dimmed in dramatic, never-before-seen ways. Models to explain its erratic behavior were so lacking that some considered the possibility that alien megastructures built to capture sunlight around the host star (think Dyson Spheres) might be the cause.

But a search using the SETI Institute’s Allen Telescope Array for two weeks in October detected no significant radio signals or other signs of intelligent life emanating from the star’s vicinity. Something had passed in front of the star and blocked its light, but what?

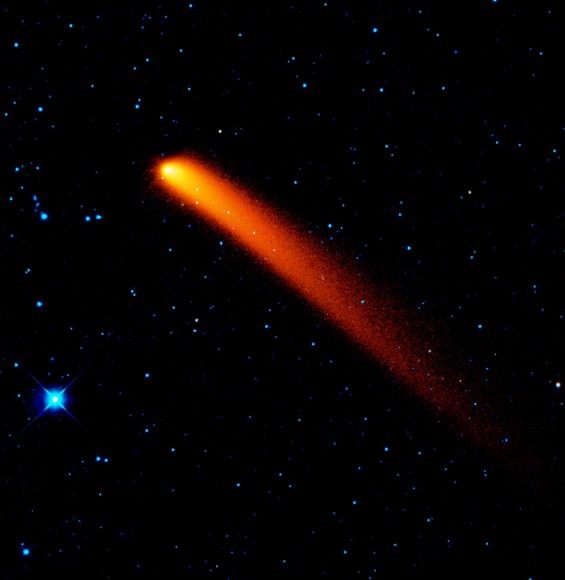

Shattered comets and asteroids were also suggested as possible explanations — dust and ground-up rock would be at the right temperature to glow in the infrared — but Kepler could only observe in visible light where any debris would be invisible or swamped by the light of the star. So researchers looked through older observations made in 2010 by the Wide Field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) space telescope. Unfortunately, WISE observed the star before the strange variations were seen and therefore before any putative dust-busting collisions.

Not to be stymied, astronomers next checked out the data from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, which like WISE, is optimized for infrared light. Spitzer just happened to observe KIC 8462852 much more recently in 2015.

“Spitzer has observed all of the hundreds of thousands of stars where Kepler hunted for planets, in the hope of finding infrared emission from circumstellar dust,” said Michael Werner, the Spitzer project scientist and the lead investigator of that particular Spitzer/Kepler observing program.

I’d love to report that Spitzer tracked down glowing dust but no, it also came up empty-handed. This makes the idea of an asteroidal smash-up very unlikely, but not one involving comets according to Massimo Marengo of Iowa State University (Ames) who led the new study. Marengo proposes that cold comets are responsible. Picture a family of comets traveling on a very long, eccentric orbit around the star with a very large comet at the head of the pack responsible for the big fading seen by Kepler in 2011. Later, in 2013, the rest of the comet family, a band of various-sized fragments lagging behind, would have passed in front of the star and again blocked its light. By 2015, the comets would have moved even farther away on their long orbital journey, leaving no detectable infrared excess.

“This is a very strange star,” said Marengo. “It reminds me of when we first discovered pulsars. They were emitting odd signals nobody had ever seen before, and the first one discovered was named LGM-1 after ‘Little Green Men.'”

Clearly, more long-term observations are needed. And frankly, I’m still puzzled why cold or less active comets might still not be detected by their glowing dust. But let’s assume for a moment the the comet idea is correct. If so, we should expect to see similar dips in KIC 8462852’s light as the comet swarm swings around again.

The problem with this would be if the comet swarm is quite far away from the star and there isn’t a transit for decades or longer, though… I know, “statistically” for us to have observed the swam JUST THEN is low, but it’s possible.

CJSF

CJSF,

That’s what I’m having a problem with – no detection in 2010 apparently prior to breakup, then a breakup and then no detection just 5 years later. If the comets are moving that fast, we should see them soon. I wish I could get my hand on the paper to fill in the details.

A preprint of the Marengo paper has been posted on arXiv:

http://fr.arxiv.org/abs/1511.07908

Best guess is the comets are not on a stable elliptical orbit. Could be we will only see two passes every dozen or more years.

Could it be that we have seen a dusty debris cloud passing between us and that star? A foreground Bok globule(s)?

Aqua,

Interesting thought. Maybe. It would seem that it would have been detected if relatively nearby. Globules are usually associated with star forming regions and there don’t appear to be any of those near the Kepler star as far as I can tell on deep maps.

If a large “gravel pile” type asteroid was gravitationaly dispersed, there might be a large cloud of small objects with little dust.

A planetary collision involving a gas giant would eject a large quantity of gas as molecules composed of whatever the atmosphere is been made of. Gas doesn’t glow in the IR like solid material except at occasional and discrete wavelengths. It can absorb visible light of a given frequency, and above, the frequency depending on the molecule. It would take a relatively small amount of ejected mass to cover a large area. The gas would probably not form smooth sheets, but would form irregular swaths, thus blocking the light we see in a non-linear way.

The argument that we are unlikely to have just observed such a dramatic planetary collision is, of course, true. But then we have observed thousands (millions?) of stars and this is the first one of its type that we have found. Any statistical argument here is based on small numbers (like one star) must be suspect.