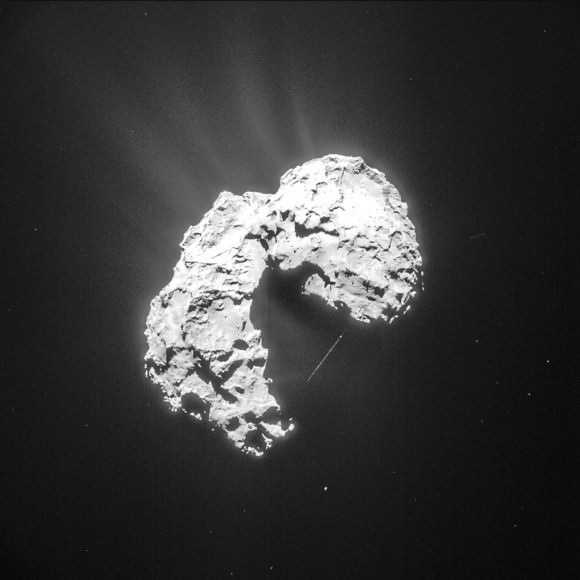

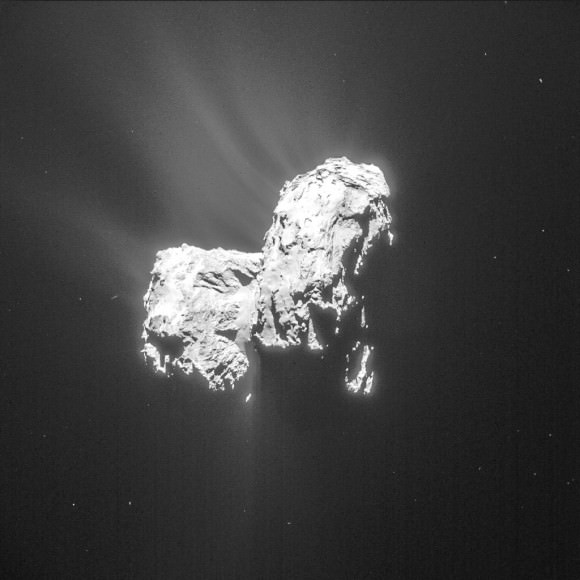

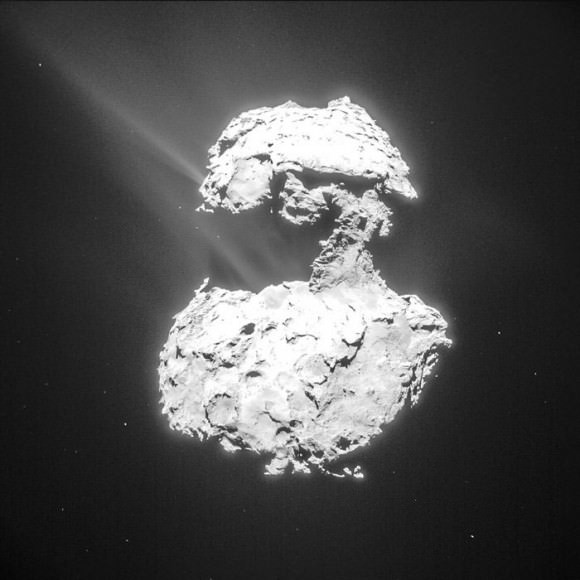

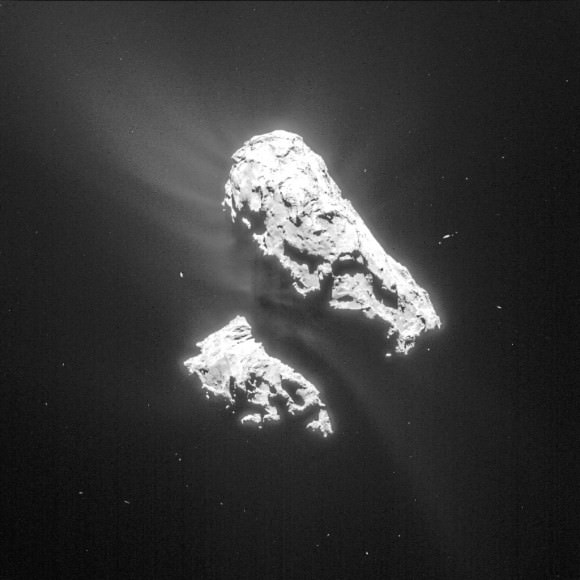

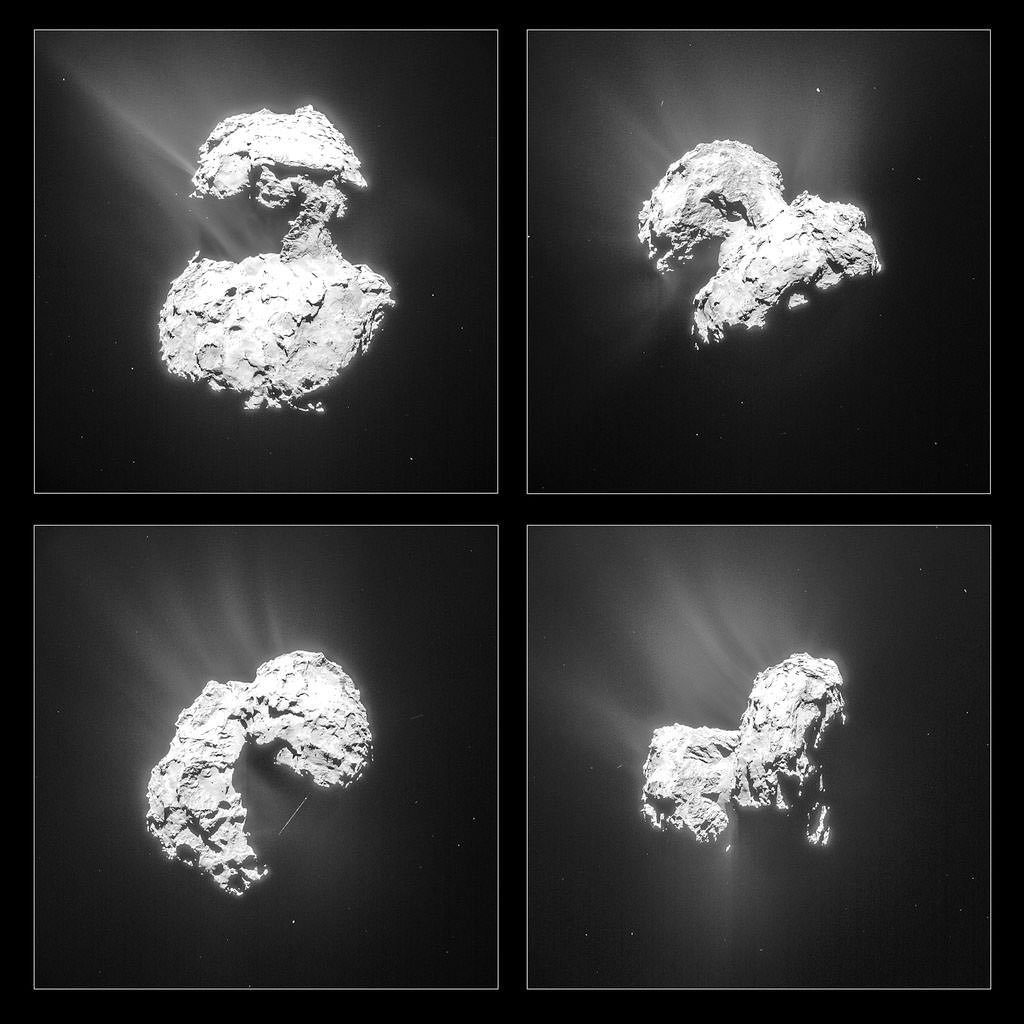

Tell me this montage shouldn’t be hanging in the Lourve Museum. Every time I think I’ve seen the “best image” of Rosetta’s comet, another one takes its place. Or in this case four! When you and I look at a comet in our telescopes or binoculars, we’re seeing mostly the coma, the bright, fluffy head of the comet composed of dust and gas ejected by the tiny, completely invisible, icy nucleus.

As we examine this beautiful set of photos, we’re privileged to see the individual fountains of gas and dust that leave the comet to create the coma. Much of the outgassing comes from the narrow neck region between the two lobes.

All were taken between February 25-27 at distances around 50-62 miles (80 to 100 km) from the center of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Looking more closely, the comet nucleus appears to be “glowing” with a thin layer of dust and gas suspended above the surface. In the lower left Feb. 27 image, a prominent streak is visible. While this might be a cosmic ray zap, its texture hints that it could also be a dust particle captured during the time exposure. Because it moved a significant distance across the frame, the possible comet chunk may be relatively close to the spacecraft. Just a hunch.

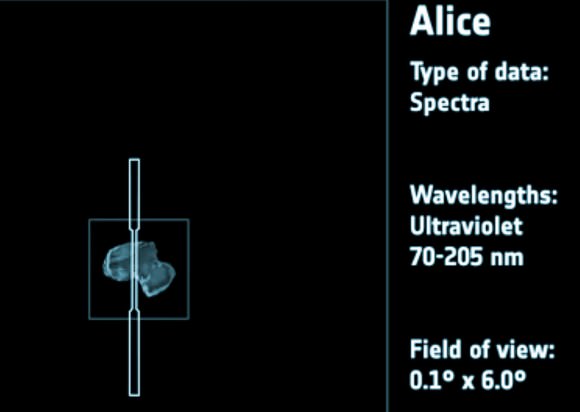

While most of Rosetta’s NAVCAM images are taken for navigation purposes, these images were obtained to provide context in support of observations performed at the same time with the Alice ultraviolet (UV) imaging spectrograph on Rosetta. Observing in ultraviolet light, Alice determines the composition of material in coma, the nucleus and where they interface. Alice will also monitor the production rates of familiar molecules like H2O, CO (carbon monoxide) and CO2 as they leave the nucleus and enter 67P’s coma and tail.

From data collected so far, the Alice team has discovered that the comet is unusually dark in the ultraviolet, and that its surface shows no large water-ice patches. Water however has been detected as vapor leaving the comet as it’s warmed by the Sun. The amount varies as the nucleus rotates, but the last published measurements put the average loss rate at 1 liter (34 ounces) per second with a maximum of 5 liters per second. Vapors from sublimating carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide ice have also been detected. Sometimes one or another will dominate over water, but overall, water remains the key volatile material outgassed in the greatest quantity.

That and dust. In fact, 67P is giving off about twice as much dust as gas. We see the comet’s dual emissions by reflected sunlight, but because there’s so much less material in the jets than what makes up the nucleus, they’re fainter and require longer exposures and special processing to bring out without seriously overexposing the comet’s core.

67P’s coma will only grow thicker and more intense as it approaches perihelion on August 13.

Wow! Again Bob pulls off the front page headlines these photos are Fantastic! The Comet almost looks alive it has that 3 month old Child look while still in its Mother, And in a strange way that is exactly what Comets do, They seed Planets with water and the building blocks of life Oh! How Wonderful our Cosmos. And please Bob show us more of your own Great Astronomical pictures. Thanks Again

Pretty amazing. We are watching it come back to life. Kind of like Frankenstein’s monster or seeing a ghostly aberration, which I’ve never seen except also in the movies. 🙂 Quite beautiful. I agree – like a master work of art. Yet another one to add to the golden age of Astronomy.

WAY double extra groovy cool! Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko is as spectacular as anyone could have imagined.. and here comes perihelion!

Images are way too cool! Gonna be GREAT come August!!

-eh— question…

[Regarding the water: Didn’t they conclude that this comet’s water didn’t match Earth’s water?]

Hi Plenum, 67P/ contains about 3 times more deuterium (a heavy form of hydrogen) than water found on Earth. Measurements from other Comets have found water with similar deuterium contents to that on Earth. But the strange composition of 67Ps water suggests that the picture of Comets bringing water to Earth is too simplistic and that Earths Oceans are probably a mix of many things including Asteroids bringing water to Earth in the Great Bombardment according to New Scientist Magazine….

Very cool!

If the activity surrounding the comet is due to heating why is it majorly associated with the neck region which is in shadow more often than the lobes? Also, there is evidently no sign of water ice on the comet surface; is it water that is detected in the coma or a proxy which is assumed to indicate the presence of water and, if so, could there be another source for it?

Taygatayga,

That is an excellent question. It would seem that more ice must be near the surface or possibly exposed there than in other places. Since the comet is rotating, the photos only show one quick view at a time, so the region no doubt spends some time in sunlight during its 12.4 hour rotation. Actual water has been detected in the coma along with carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide.

To go with Bob’s excellent answer, it’s also likely that many of the jets you see actually originate in the lit portions of P67. It’s just that you can’t see their point of origin in the images, because the faint jets don’t stand out against the relatively bright surface of the comet itself. Other jets might originate on the other side of P67 so that it looks like they’re venting from the visible edge of the comet.

All the pictures show the out-gassing going in the 10-11 o’clock direction regardless of the orientation of the body. Is that always the “away from the sun” direction?