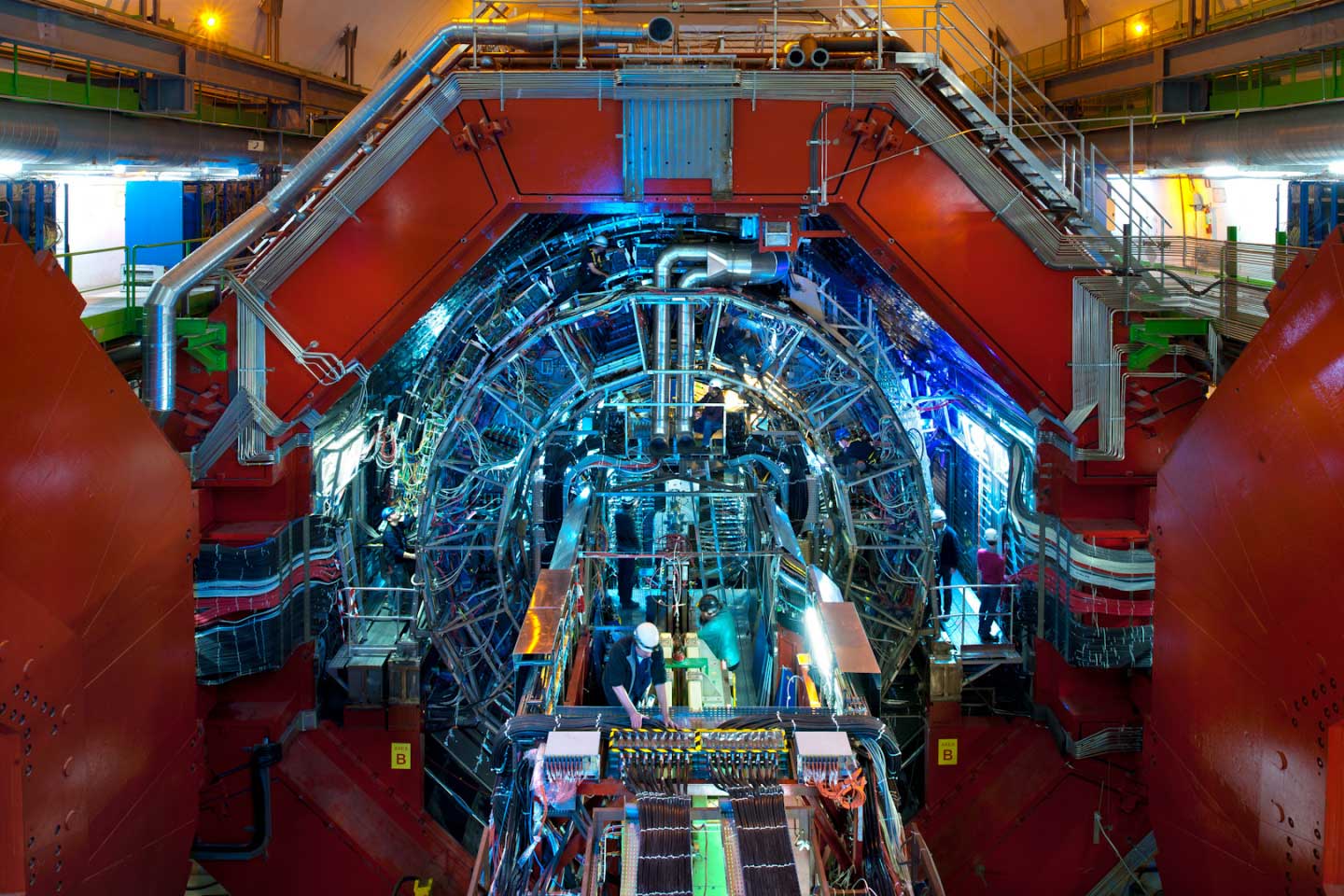

In 2012, two previous dark matter detection experiments—the Large Underground Xenon (LUX) and ZonEd Proportional scintillation in Liquid Noble gases (ZEPLIN)—came together to form the LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) experiment. Since it commenced operations, this collaboration has conducted the most sensitive search ever mounted for Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs) – one of the leading Dark Matter candidates. This collaboration includes around 250 scientists from 39 institutions in the U.S., U.K., Portugal, Switzerland, South Korea, and Australia.

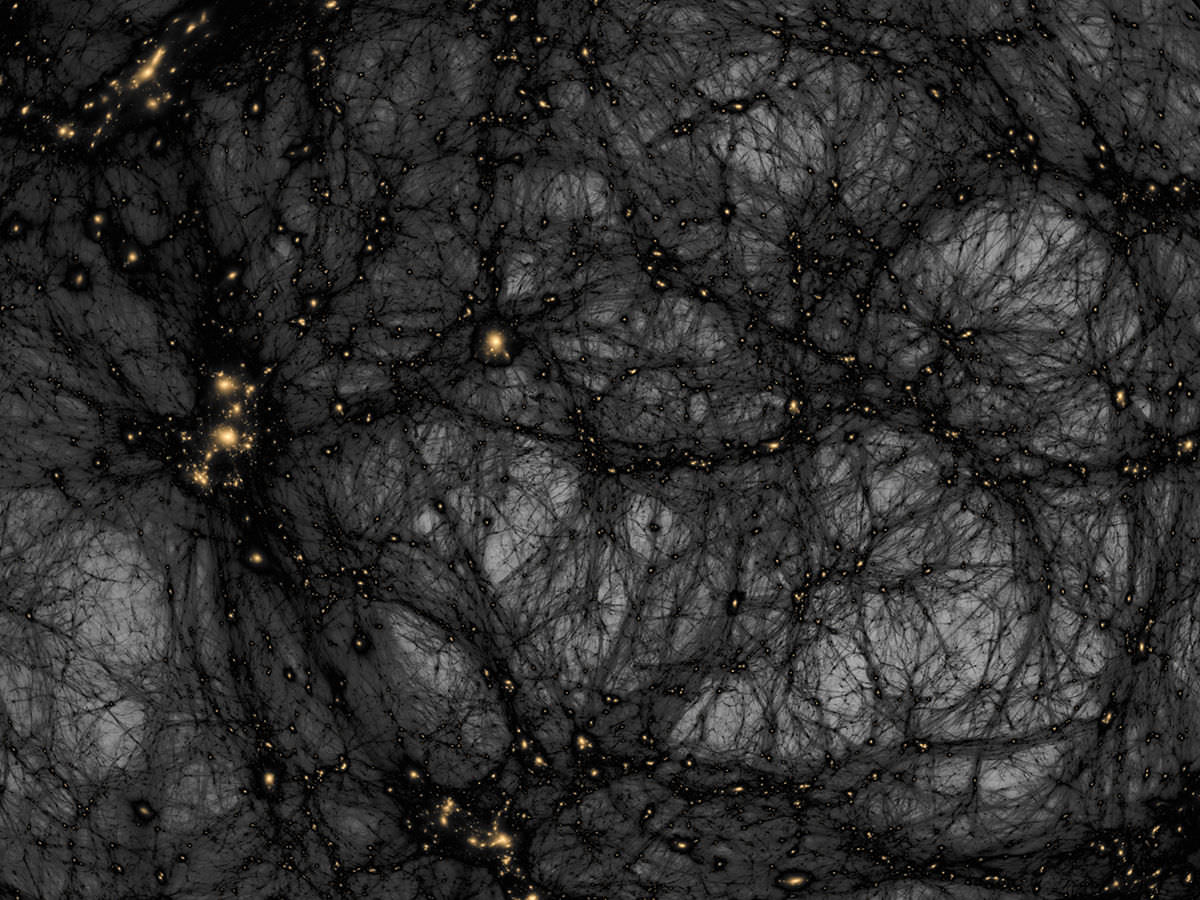

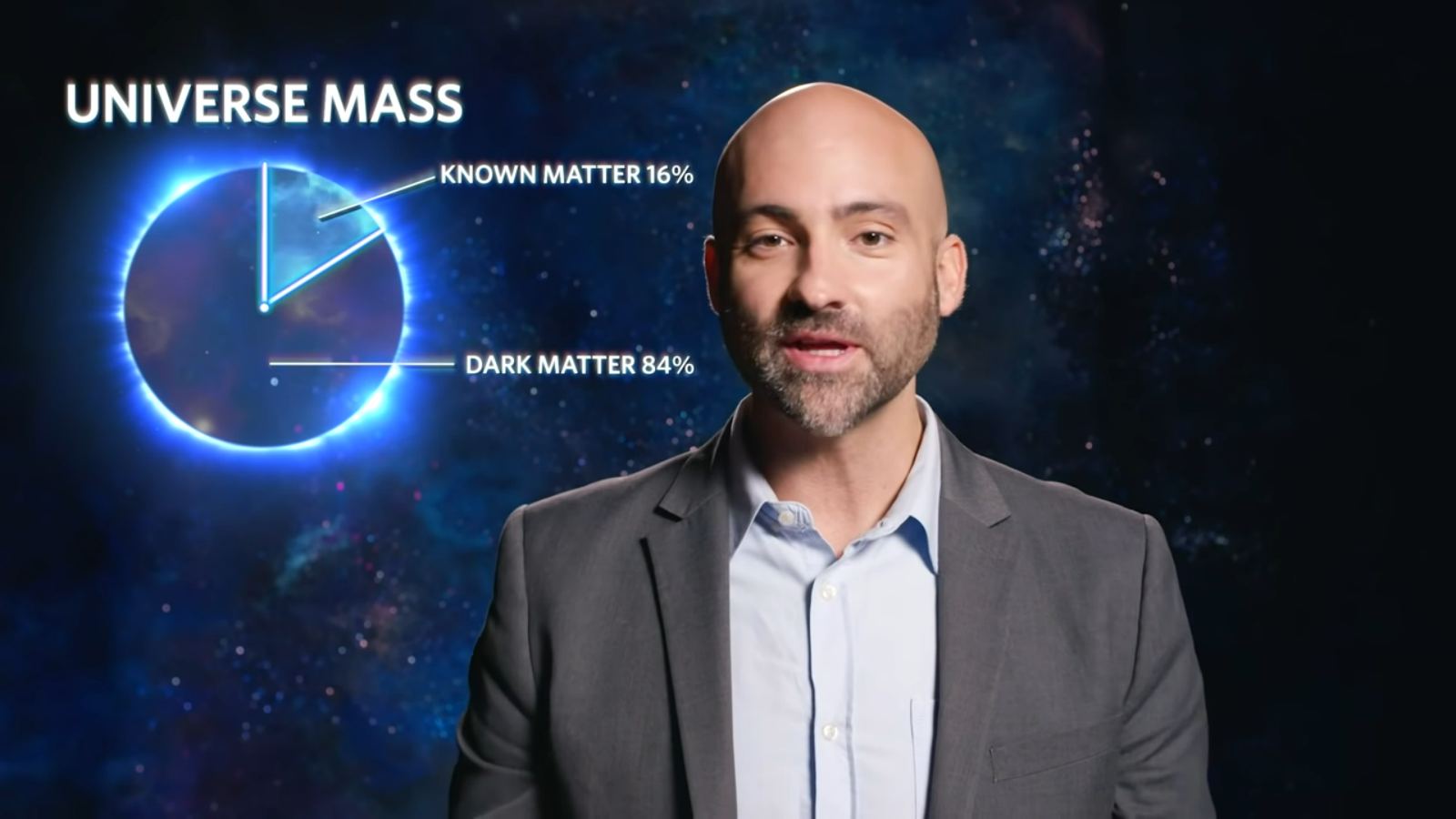

On Monday, August 26th, the latest results from the LUX-ZEPLIN project were shared at two scientific conferences. These results were celebrated by scientists at the University of Albany‘s Department of Physics, including Associate Professors Cecilia Levy and Matthew Szydagis (two members of the experiment). This latest result is nearly five times more sensitive than the previous result and found no evidence of WIMPs above a mass of 9 GeV/c2. These are the best-ever limits on WIMPS and a crucial step toward finding the mysterious invisible mass that makes up 85% of the Universe.

Continue reading “Largest Dark Matter Detector is Narrowing Down Dark Matter Candidate”