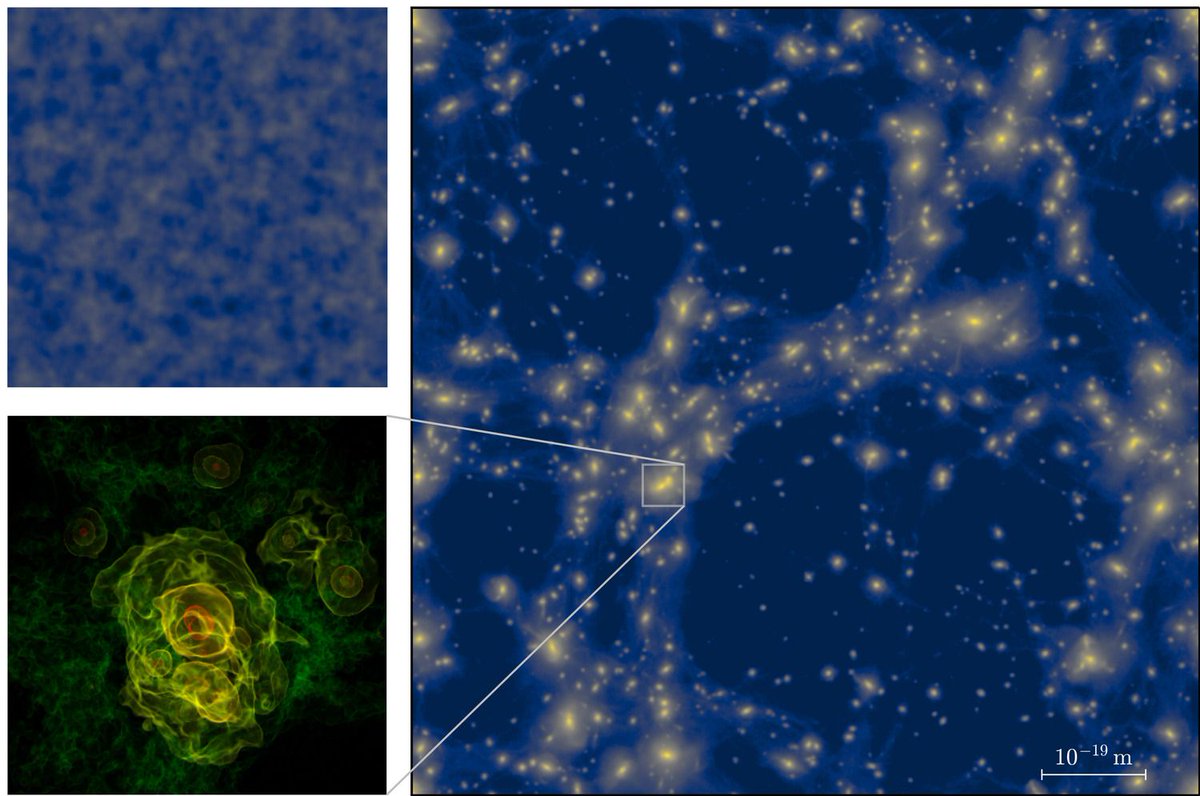

The Big Bang remains the best way to explain what happened at the beginning of the Universe. However, the incredible energies flowing during the early part of the bang are almost incomprehensive to our everyday experience. Luckily, computers aren’t so attached to normal human ways of thinking and have long been used to model the early universe right after the Bang. Now, a team from the University of Göttingen have created the most comprehensive model of what exactly happened in that very early stage of the universe – one trillionth of a second after the Big Bang.

Continue reading “Simulating the Universe a Trillionth of a Second After the Big Bang”Astronomers set a new Record and Find the Farthest Galaxy. Its Light Took 13.4 Billion Years to Reach us

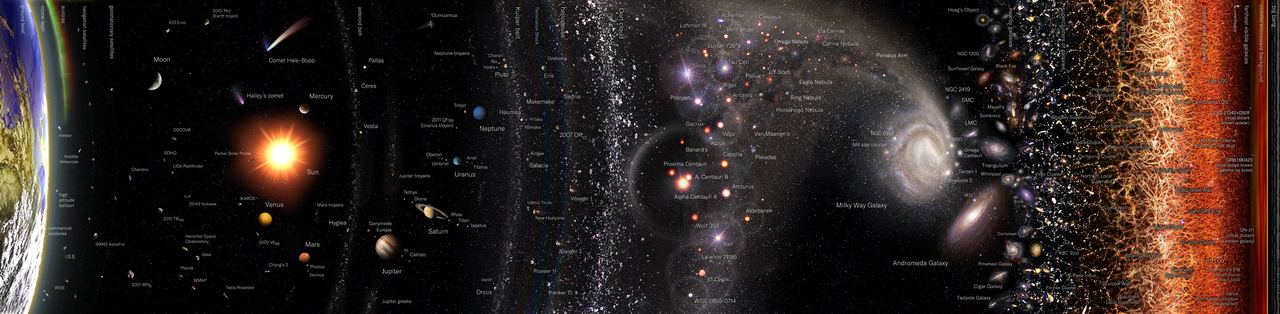

Since time immemorial, philosophers and scholars have contemplated the beginning of time and even tried to determine when all things began. It’s only been in the age of modern astronomy that we’ve come close to answering that question with a fair degree of certainty. According to the most widely-accepted cosmological models, the Universe began with the Bang Bang roughly 13.8 billion years ago.

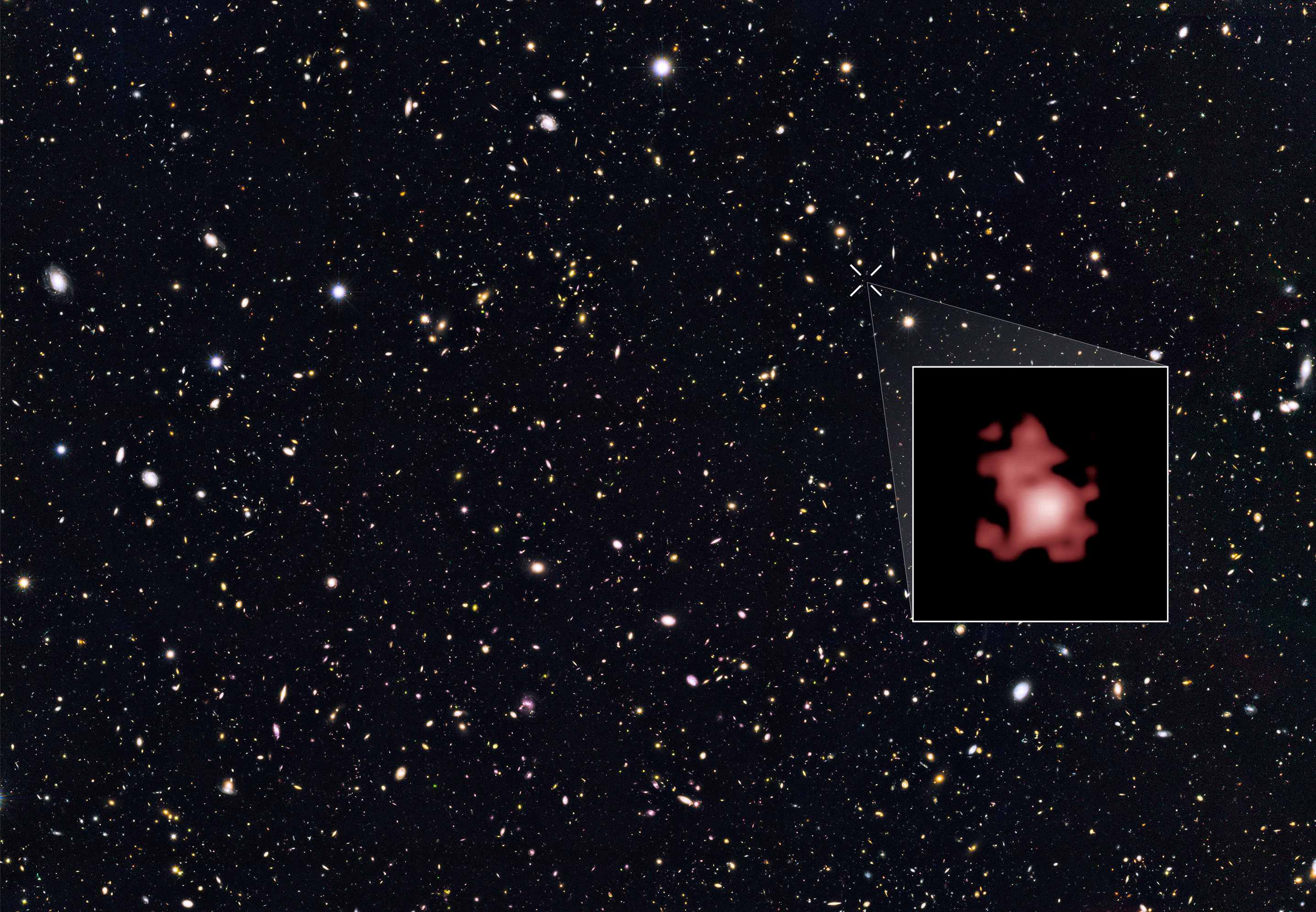

Even so, astronomers are still uncertain about what the early Universe looked like since this period coincided with the cosmic “Dark Ages.” Therefore, astronomers keep pushing the limits of their instruments to see when the earliest galaxies formed. Thanks to new research by an international team of astronomers, the oldest and most distant galaxy observed in our Universe to date (GN-z11) has been identified!

Continue reading “Astronomers set a new Record and Find the Farthest Galaxy. Its Light Took 13.4 Billion Years to Reach us”Next Generation Gravitational Wave Detectors Should be Able to see the Primordial Waves From the Big Bang

Gravitational-wave astronomy is still in its youth. Because of this, the gravitational waves we can observe come from powerful cataclysmic events. Black holes consuming each other in a violent chirp of spacetime, or neutron stars colliding in a tremendous explosion. Soon we might be able to observe the gravitational waves of supernovae, or supermassive black holes merging billions of light-years away. But underneath the cacophony is a very different gravitational wave. But if we can detect them, they will help us solve one of the deepest cosmological mysteries.

Continue reading “Next Generation Gravitational Wave Detectors Should be Able to see the Primordial Waves From the Big Bang”How were Supermassive Black Holes Already Forming and Releasing Powerful Jets Shortly After the Big Bang?

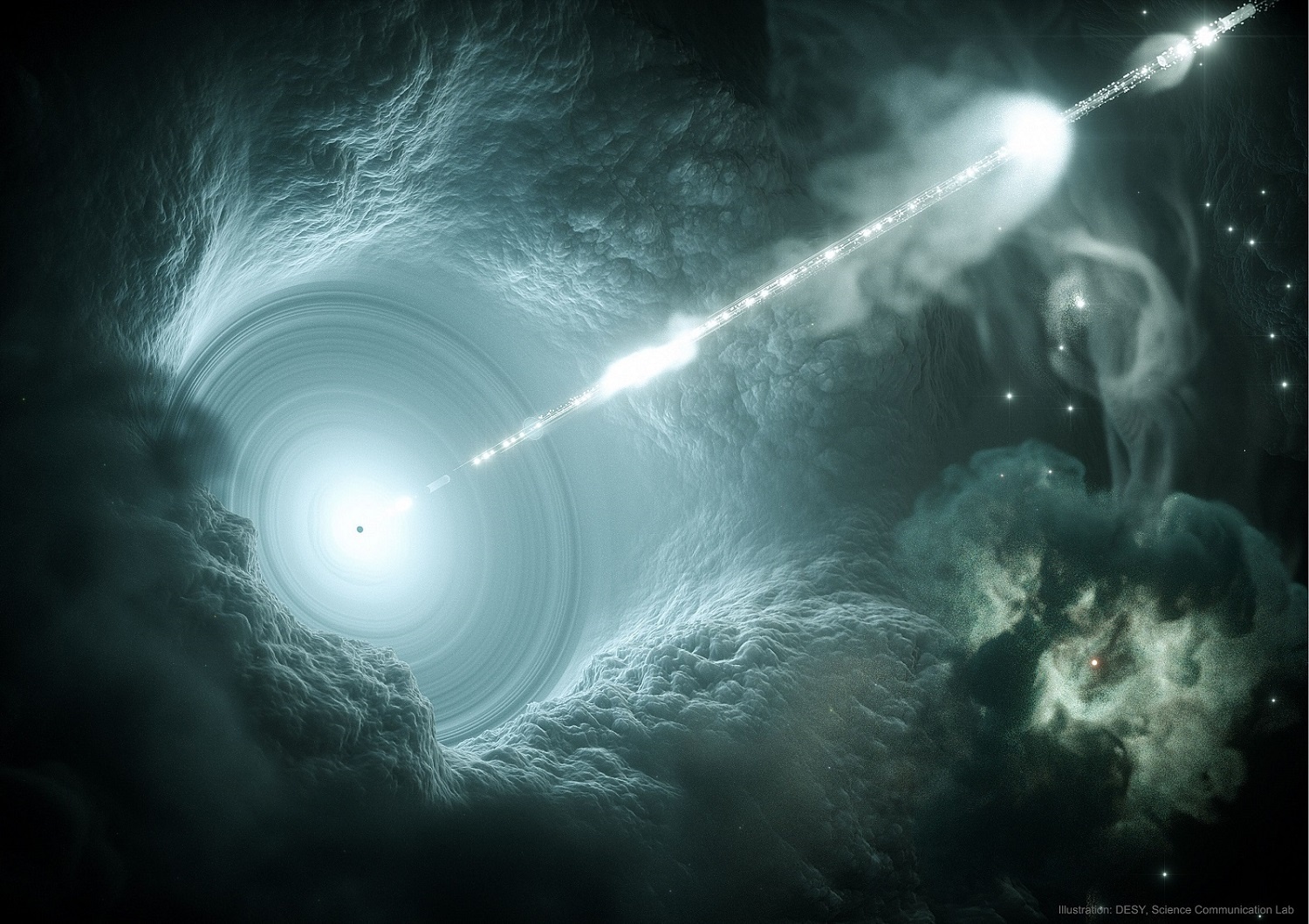

In the past few decades, astronomers have been able to look farther into the Universe (and also back in time), almost to the very beginnings of the Universe. In so doing, they’ve learned a great deal about some of the earliest galaxies in the Universe and their subsequent evolution. However, there are still some things that are still off-limits, like when galaxies with supermassive black holes (SMBHs) and massive jets first appeared.

According to recent studies from the International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA) and a team of astronomers from Japan and Taiwan provide new insight on how supermassive black holes began forming just 800 million years after the Big Bang, and relativistic jets less than 2 billion years after. These results are part of a growing case that shows how massive objects in our Universe formed sooner than we thought.

Continue reading “How were Supermassive Black Holes Already Forming and Releasing Powerful Jets Shortly After the Big Bang?”Blazar Found Blazing When the Universe was Only a Billion Years Old

Since the 1950s, astronomers have known of galaxies that have particularly bright centers – aka. Active Galactic Nuclei (AGNs) or quasars. This luminosity is the result of supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at their centers consuming matter and releasing electromagnetic energy. Further studies revealed that there are some quasars that appear particularly bright because their relativistic jets are directed towards Earth.

In 1978, astronomer Edward Speigel coined the term “blazar” to describe this particular class of object. Using the telescopes at the Large Binocular Telescope Observatory (LBTO) in Arizona, a research team recently observed a blazar located 13 billion light-years from Earth. This object, designated PSO J030947.49+271757.31 (or PSO J0309+27), is the most distant blazar ever observed and foretells the existence of many more!

Continue reading “Blazar Found Blazing When the Universe was Only a Billion Years Old”Is the “D-star Hexaquark” the Dark Matter Particle?

Since the 1960s, astronomers have theorized that all the visible matter in the Universe (aka. baryonic or “luminous matter) constitutes just a small fraction of what’s actually there. In order for the predominant and time-tested theory of gravity to work (as defined by General Relativity), scientists have had to postulate that roughly 85% of the mass in the Universe consists of “Dark Matter”.

Despite many decades of study, scientists have yet to find any direct evidence of Dark Matter and the constituent particle and its origins remain a mystery. However, a team of physicists from the University of York in the UK has proposed a new candidate particle that was just recently discovered. Known as the d-star hexaquark, this particle could have formed the “Dark Matter” in the Universe during the Big Bang.

Continue reading “Is the “D-star Hexaquark” the Dark Matter Particle?”Life Could be Common Across the Universe, Just Not in Our Region

The building blocks of life can, and did, spontaneously assemble under the right conditions. That’s called spontaneous generation, or abiogenesis. Of course, many of the details remain hidden to us, and we just don’t know exactly how it all happened. Or how frequently it could happen.

Continue reading “Life Could be Common Across the Universe, Just Not in Our Region”Astronomers Are About to Detect the Light from the Very First Stars in the Universe

A team of scientists working with the Murchison Widefield Array (WMA) radio telescope are trying to find the signal from the Universe’s first stars. Those first stars formed after the Universe’s Dark Ages. To find their first light, the researchers are looking for the signal from neutral hydrogen, the gas that dominated the Universe after the Dark Ages.

Continue reading “Astronomers Are About to Detect the Light from the Very First Stars in the Universe”The First Stars Formed Very Quickly

Ever since astronomers realized that the Universe is in a constant state of expansion and that a massive explosion likely started it all 13.8 billion years ago (the Big Bang), there have been unresolved questions about when and how the first stars formed. Based on data gathered by NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) and similar missions, this is believed to have happened about 100 million years after the Big Bang.

Much of the details of how this complex process worked have remained a mystery. However, new evidence gathered by a team led by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy indicates that the first stars must have formed rather quickly. Using data from the Magellan Telescopes at Las Campanas Observatory, the team observed a cloud of gas where star formation was taking place just 850 million years after the Big Bang.

Continue reading “The First Stars Formed Very Quickly”What Was The First Color In The Universe?

The universe bathes in a sea of light, from the blue-white flickering of young stars to the deep red glow of hydrogen clouds. Beyond the colors seen by human eyes, there are flashes of x-rays and gamma rays, powerful bursts of radio, and the faint, ever-present glow of the cosmic microwave background. The cosmos is filled with colors seen and unseen, ancient and new. But of all these, there was one color that appeared before all the others, the first color of the universe.

Continue reading “What Was The First Color In The Universe?”