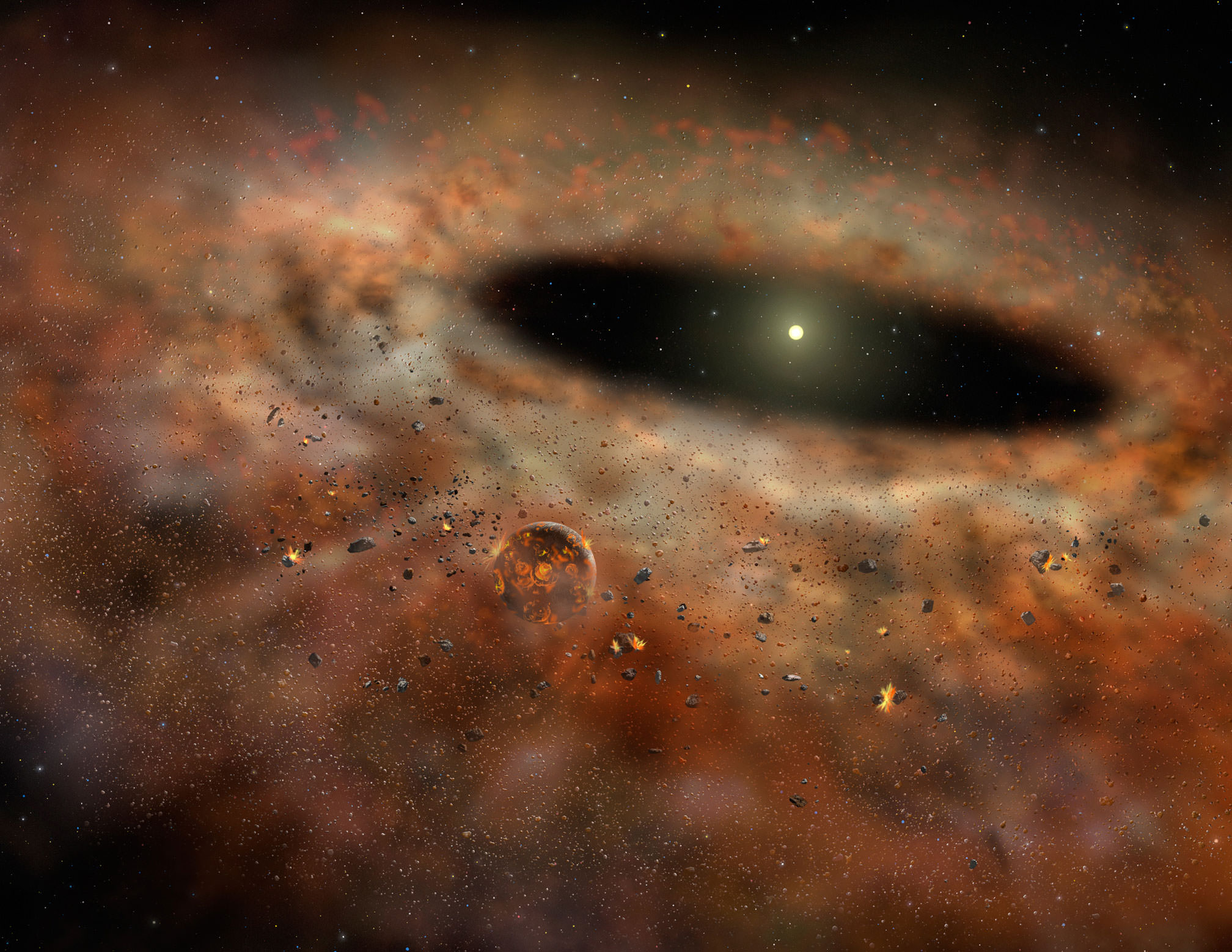

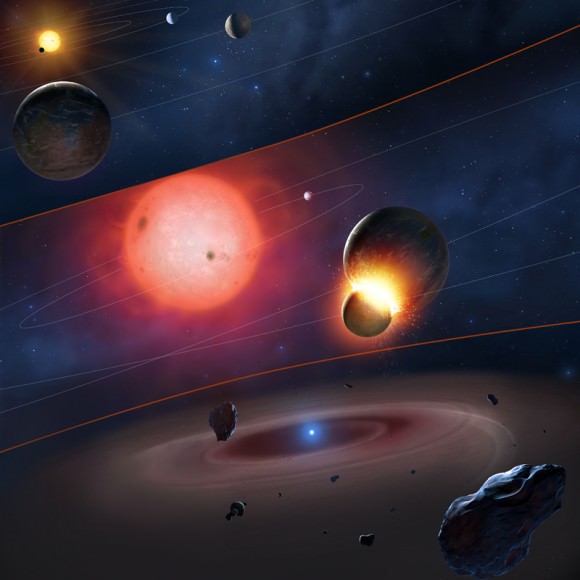

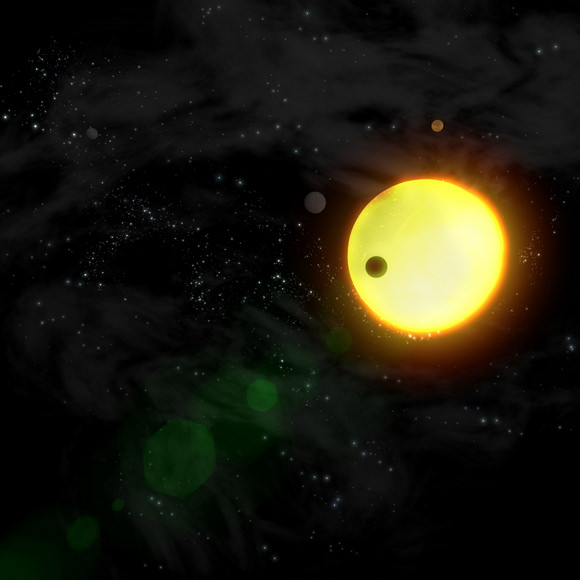

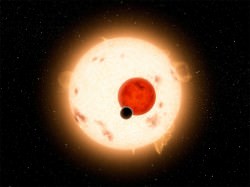

How’s this for a depressing look into Earth’s potential future: astronomers have witnessed the first evidence of a planet’s destruction by its aging star as it expands into a red giant.

“A similar fate may await the inner planets in our solar system, when the Sun becomes a red giant and expands all the way out to Earth’s orbit some five-billion years from now,” said Alex Wolszczan, from Penn State, University, who led a team which found evidence of a missing planet having been devoured by its parent star. Wolszczan also is the discoverer of the first planet ever found outside our solar system.

The planet-eating culprit, a red-giant star named BD+48 740 is older than the Sun and now has a radius about eleven times bigger than our Sun.

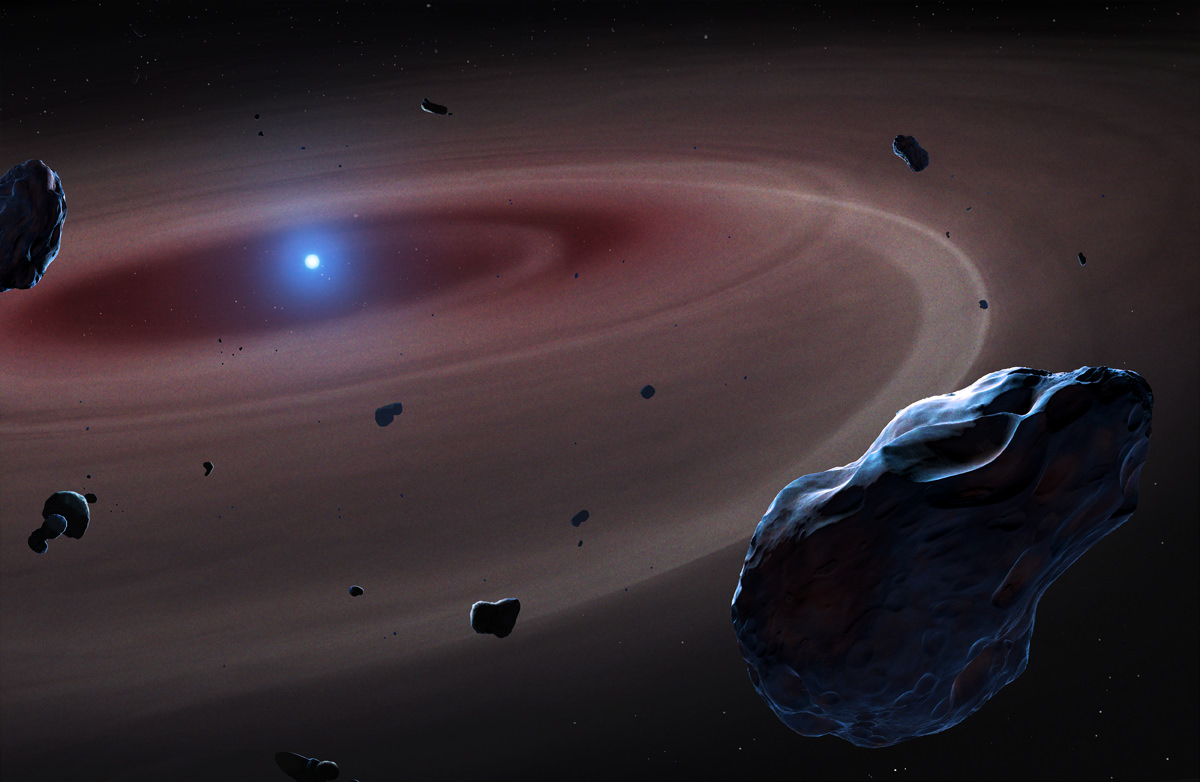

The evidence the astronomers found was a massive planet in a surprising highly elliptical orbit around the star – indicating a missing planet — plus the star’s wacky chemical composition.

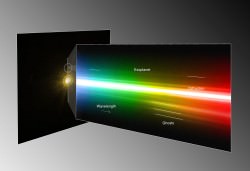

“Our detailed spectroscopic analysis reveals that this red-giant star, BD+48 740, contains an abnormally high amount of lithium, a rare element created primarily during the Big Bang 14 billion years ago,” said team member Monika Adamow from the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, Poland. “Lithium is easily destroyed in stars, which is why its abnormally high abundance in this older star is so unusual.

“Theorists have identified only a few, very specific circumstances, other than the Big Bang, under which lithium can be created in stars,” Wolszczan added. “In the case of BD+48 740, it is probable that the lithium production was triggered by a mass the size of a planet that spiraled into the star and heated it up while the star was digesting it.”

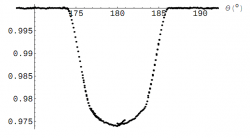

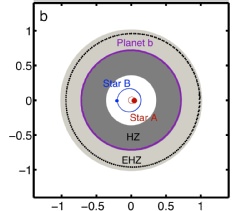

The other piece of evidence discovered by the astronomers is the highly elliptical orbit of the star’s newly discovered massive planet, which is at least 1.6 times as massive as Jupiter.

“We discovered that this planet revolves around the star in an orbit that is only slightly wider than that of Mars at its narrowest point, but is much more extended at its farthest point,” said Andrzej Niedzielski, also from Nicolaus Copernicus University. “Such orbits are uncommon in planetary systems around evolved stars and, in fact, the BD+48 740 planet’s orbit is the most elliptical one detected so far.”

The Hobby-Eberly Telescope

Because gravitational interactions between planets are responsible for such peculiar orbits, the astronomers suspect that the dive of the missing planet toward the star could have given the surviving massive planet a burst of energy, throwing it into an eccentric orbit like a boomerang.

“Catching a planet in the act of being devoured by a star is an almost improbable feat to accomplish because of the comparative swiftness of the process, but the occurrence of such a collision can be deduced from the way it affects the stellar chemistry,” said Eva Villaver of the Universidad Autonoma de Madrid in Spain Villaver. “The highly elongated orbit of the massive planet we discovered around this lithium-polluted red-giant star is exactly the kind of evidence that would point to the star’s recent destruction of its now-missing planet.”

The team used the Hobby-Eberly Telescope – searching for planets – when they detected evidence of the missing planet’s destruction.

The paper describing this discovery is posted in an early online edition of the Astrophysical Journal Letters (Adamow et al. 2012, ApJ, 754, L15), or another version is available on arXiv.

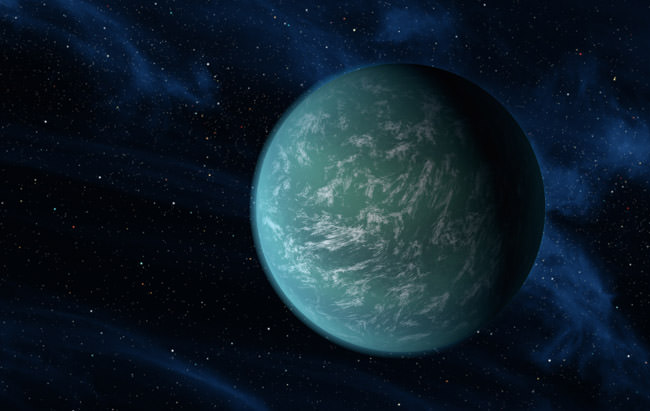

Lead image caption: Artist’s impression of a red giant star. Image credit: ESO