[/caption]

We’ve all wondered at some point or another what mysteries our Solar System holds. After all, the eight planets (plus Pluto and all those other dwarf planets) orbit within a very small volume of the heliosphere (the volume of space dominated by the influence of the Sun), what’s going on in the rest of the volume we call our home? As we push more robots into space, improve our observational capabilities and begin to experience space for ourselves, we learn more and more about the nature of where we come from and how the planets have evolved. But even with our advancing knowledge, we would be naive to think we have all the answers, so much still needs to be uncovered. So, from a personal point of view, what would I consider to be the greatest mysteries within our Solar System? Well, I’m going to tell you my top ten favourites of some more perplexing conundrums our Solar System has thrown at us. So, to get the ball rolling, I’ll start in the middle, with the Sun. (None of the following can be explained by dark matter, in case you were wondering… actually it might, but only a little…)

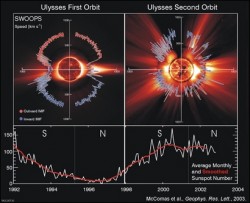

10. Solar Pole Temperature Mismatch

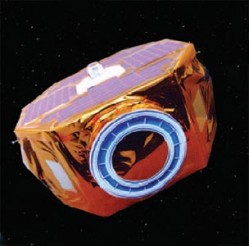

Why is the Sun’s South Pole cooler than the North Pole? For 17 years, the solar probe Ulysses has given us an unprecedented view of the Sun. After being launched on Space Shuttle Discovery way back in 1990, the intrepid explorer took an unorthodox trip through the Solar System. Using Jupiter for a gravitational slingshot, Ulysses was flung out of the ecliptic plane so it could pass over the Sun in a polar orbit (spacecraft and the planets normally orbit around the Sun’s equator). This is where the probe journeyed for nearly two decades, taking unprecedented in-situ observations of the solar wind and revealing the true nature of what happens at the poles of our star. Alas, Ulysses is dying of old age, and the mission effectively ended on July 1st (although some communication with the craft remains).

However, observing uncharted regions of the Sun can create baffling results. One such mystery result is that the South Pole of the Sun is cooler than the North Pole by 80,000 Kelvin. Scientists are confused by this discrepancy as the effect appears to be independent of the magnetic polarity of the Sun (which flips magnetic north to magnetic south every 11-years). Ulysses was able to gauge the solar temperature by sampling the ions in the solar wind at a distance of 300 million km above the North and South Poles. By measuring the ratio of oxygen ions (O6+/O7+), the plasma conditions at the base of the coronal hole could be measured.

This remains an open question and the only explanation solar physicists can currently come up with is the possibility that the solar structure in the polar regions differ in some way. It’s a shame Ulysses bit the dust, we could do with a polar orbiter to take more results (see Ulysses Spacecraft Dying of Natural Causes).

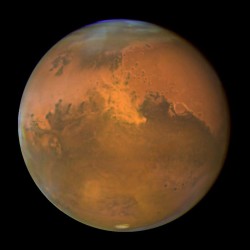

9. Mars Mysteries

Why are the Martian hemispheres so radically different? This is one mystery that had frustrated scientists for years. The northern hemisphere of Mars is predominantly featureless lowlands, whereas the southern hemisphere is stuffed with mountain ranges, creating vast highlands. Very early on in the study of Mars, the theory that the planet had been hit by something very large (thus creating the vast lowlands, or a huge impact basin) was thrown out. This was primarily because the lowlands didn’t feature the geography of an impact crater. For a start there is no crater “rim.” Plus the impact zone is not circular. All this pointed to some other explanation. But eagle-eyed researchers at Caltech have recently revisited the impactor theory and calculated that a huge rock between 1,600 to 2,700 km diameter can create the lowlands of the northern hemisphere (see Two Faces of Mars Explained).

Bonus mystery: Does the Mars Curse exist? According to many shows, websites and books there is something (almost paranormal) out in space eating (or tampering with) our robotic Mars explorers. If you look at the statistics, you would be forgiven for being a little shocked: Nearly two-thirds of all Mars missions have failed. Russian Mars-bound rockets have blown up, US satellites have died mid-flight, British landers have pock-marked the Red Planet’s landscape; no Mars mission is immune to the “Mars Triangle.” So is there a “Galactic Ghoul” out there messing with our ‘bots? Although this might be attractive to some of us superstitious folk, the vast majority of spacecraft lost due to The Mars Curse is mainly due to heavy losses during the pioneering missions to Mars. The recent loss rate is comparable to the losses sustained when exploring other planets in the Solar System. Although luck may have a small part to play, this mystery is more of a superstition than anything measurable (see The “Mars Curse”: Why Have So Many Missions Failed?).

8. The Tunguska Event

What caused the Tunguska impact? Forget Fox Mulder tripping through the Russian forests, this isn’t an X-Files episode. In 1908, the Solar System threw something at us… but we don’t know what. This has been an enduring mystery ever since eye witnesses described a bright flash (that could be seen hundreds of miles away) over the Podkamennaya Tunguska River in Russia. On investigation, a huge area had been decimated; some 80 million trees had been felled like match sticks and over 2,000 square kilometres had been flattened. But there was no crater. What had fallen from the sky?

This mystery is still an open case, although researchers are pinning their bets of some form of “airburst” when a comet or meteorite entered the atmosphere, exploding above the ground. A recent cosmic forensic study retraced the steps of a possible asteroid fragment in the hope of finding its origin and perhaps even finding the parent asteroid. They have their suspects, but the intriguing thing is, there is next-to-no meteorite evidence around the impact site. So far, there doesn’t appear to be much explanation for that, but I don’t think Mulder and Scully need be involved (see Tunguska Meteoroid’s Cousins Found?).

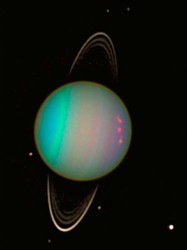

7. Uranus’ Tilt

Why does Uranus rotate on its side? Strange planet is Uranus. Whilst all the other planets in the Solar System more-or-less have their axis of rotation pointing “up” from the ecliptic plane, Uranus is lying on its side, with an axial tilt of 98 degrees. This means that for very long periods (42 years at a time) either its North or South Pole points directly at the Sun. The majority of the planets have a “prograde” rotation; all the planets rotate counter-clockwise when viewed from above the Solar System (i.e. above the North Pole of the Earth). However, Venus does the exact opposite, it has a retrograde rotation, leading to the theory that it was kicked off-axis early in its evolution due to a large impact. So did this happen to Uranus too? Was it hit by a massive body?

Some scientists believe that Uranus was the victim of a cosmic hit-and-run, but others believe there may be a more elegant way of describing the gas giant’s strange configuration. Early in the evolution of the Solar System, astrophysicists have run simulations that show the orbital configuration of Jupiter and Saturn may have crossed a 1:2 orbital resonance. During this period of planetary upset, the combined gravitational influence of Jupiter and Saturn transferred orbital momentum to the smaller gas giant Uranus, knocking it off-axis. More research needs to be carried out to see if it was more likely that an Earth-sized rock impacted Uranus or whether Jupiter and Saturn are to blame.

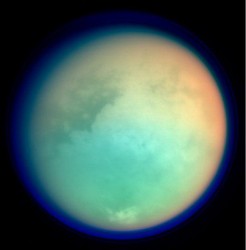

6. Titan’s Atmosphere

Why does Titan have an atmosphere? Titan, one of Saturn’s moons, is the only moon in the Solar System with a significant atmosphere. It is the second biggest moon in the Solar System (second only to Jupiter’s moon Ganymede) and about 80% more massive than Earth’s Moon. Although small when compared with terrestrial standards, it is more Earth-like than we give it credit for. Mars and Venus are often cited as Earth’s siblings, but their atmospheres are 100 times thinner and 100 times thicker, respectively. Titan’s atmosphere on the other hand is only one and a half times thicker than Earth’s, plus it is mainly composed of nitrogen. Nitrogen dominates Earth’s atmosphere (at 80% composition) and it dominates Titans atmosphere (at 95% composition). But where did all this nitrogen come from? Like on Earth, it’s a mystery.

Titan is such an interesting moon and is fast becoming the prime target to search for life. Not only does it have a thick atmosphere, its surface is crammed full with hydrocarbons thought to be teeming with “tholins,” or prebiotic chemicals. Add to this the electrical activity in the Titan atmosphere and we have an incredible moon with a massive potential for life to evolve. But as to where its atmosphere came from… we just do not know.

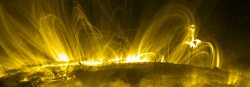

5. Solar Coronal Heating

Why is the solar atmosphere hotter than the solar surface? Now this is a question that has foxed solar physicists for over half a century. Early spectroscopic observations of the solar corona revealed something perplexing: The Sun’s atmosphere is hotter than the photosphere. In fact, it is so hot that it is comparable to the temperatures found in the core of the Sun. But how can this happen? If you switch on a light bulb, the air surrounding the glass bulb wont be hotter than the glass itself; as you get closer to a heat source, it gets warmer, not cooler. But this is exactly what the Sun is doing, the solar photosphere has a temperature of around 6000 Kelvin whereas the plasma only a few thousand kilometres above the photosphere is over 1 million Kelvin. As you can tell, all kinds of physics laws appear to be violated.

However, solar physicists are gradually closing in on what may be causing this mysterious coronal heating. As observational techniques improve and theoretical models become more sophisticated, the solar atmosphere can be studied more in-depth than ever before. It is now believed that the coronal heating mechanism may be a combination of magnetic effects in the solar atmosphere. There are two prime candidates for corona heating: nanoflares and wave heating. I for one have always been a huge advocate of wave heating theories (a large part of my research was devoted to simulating magnetohydrodynamic wave interactions along coronal loops), but there is strong evidence that nanoflares influence coronal heating too, possibly working in tandem with wave heating.

Although we are pretty certain that wave heating and/or nanoflares may be responsible, until we can insert a probe deep into the solar corona (which is currently being planned with the Solar Probe mission), taking in-situ measurements of the coronal environment, we won’t know for sure what heats the corona (see Warm Coronal Loops May Hold the Key to Hot Solar Atmosphere).

4. Comet Dust

How did dust formed at intense temperatures appear in frozen comets? Comets are the icy, dusty nomads of the Solar System. Thought to have evolved in the outermost reaches of space, in the Kuiper Belt (around the orbit of Pluto) or in a mysterious region called the Oort Cloud, these bodies occasionally get knocked and fall under the weak gravitational pull of the Sun. As they fall toward the inner Solar System, the Sun’s heat will cause the ice to vaporize, creating a cometary tail known as the coma. Many comets fall straight into the Sun, but others are more lucky, completing a short-period (if they originated in the Kuiper Belt) or long-period (if they originated in the Oort Cloud) orbit of the Sun.

But something odd has been found in the dust collected by NASA’s 2004 Stardust mission to Comet Wild-2. Dust grains from this frozen body appeared to have been formed a high temperatures. Comet Wild-2 is believed to have originated from and evolved in the Kuiper Belt, so how could these tiny samples be formed in an environment with a temperature of over 1000 Kelvin?

The Solar System evolved from a nebula some 4.6 billion years ago and formed a large accretion disk as it cooled. The samples collected from Wild-2 could only have been formed in the central region of the accretion disk, near the young Sun, and something transported them into the far reaches of the Solar System, eventually ending up in the Kuiper Belt. But what mechanism could do this? We are not too sure (see Comet Dust is Very Similar to Asteroids).

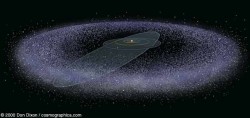

3. The Kuiper Cliff

Why does the Kuiper Belt suddenly end? The Kuiper Belt is a huge region of the Solar System forming a ring around the Sun just beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is much like the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, the Kuiper Belt contains millions of small rocky and metallic bodies, but it’s 200-times more massive. It also contains a large quantity of water, methane and ammonia ices, the constituents of cometary nuclei originating from there (see #4 above). The Kuiper Belt is also known for its dwarf planet occupant, Pluto and (more recently) fellow Plutoid “Makemake”.

The Kuiper Belt is already a pretty unexplored region of the Solar System as it is (we wait impatiently for NASA’s New Horizons Pluto mission to arrive there in 2015), but it has already thrown up something of a puzzle. The population of Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) suddenly drops off at a distance of 50 AU from the Sun. This is rather odd as theoretical models predict an increase in number of KBOs beyond this point. The drop-off is so dramatic that this feature has been dubbed the “Kuiper Cliff.”

We currently have no explanation for the Kuiper Cliff, but there are some theories. One idea is that there are indeed a lot of KBOs beyond 50 AU, it’s just that they haven’t accreted to form larger objects for some reason (and therefore cannot be observed). Another more controversial idea is that KBOs beyond the Kuiper Cliff have been swept away by a planetary body, possibly the size of Earth or Mars. Many astronomers argue against this citing a lack of observational evidence of something that big orbiting outside the Kuiper Belt. This planetary theory however has been very useful for the doomsayers out there, providing flimsy “evidence” for the existence of Nibiru, or “Planet X.” If there is a planet out there, it certainly is not “incoming mail” and it certainly is not arriving on our doorstep in 2012.

So, in short, we have no clue why the Kuiper Cliff exists…

2. The Pioneer Anomaly

Why are the Pioneer probes drifting off-course? Now this is a perplexing issue for astrophysicists, and probably the most difficult question to answer in Solar System observations. Pioneer 10 and 11 were launched back in 1972 and 1973 to explore the outer reaches of the Solar System. Along their way, NASA scientists noticed that both probes were experiencing something rather strange; they were experiencing an unexpected Sun-ward acceleration, pushing them off-course. Although this deviation wasn’t huge by astronomical standards (386,000 km off course after 10 billion km of travel), it was a deviation all the same and astrophysicists are at a loss to explain what is going on.

One main theory suspects that non-uniform infrared radiation around the probes’ bodywork (from the radioactive isotope of plutonium in its Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators) may be emitting photons preferentially on one side, giving a small push toward the Sun. Other theories are a little more exotic. Perhaps Einstein’s general relativity needs to be modified for long treks into deep space? Or perhaps dark matter has a part to play, having a slowing effect on the Pioneer spacecraft?

So far, only 30% of the deviation can be pinned on the non-uniform heat distribution theory and scientists are at a loss to find an obvious answer (see The Pioneer Anomaly: A Deviation from Einstein Gravity?).

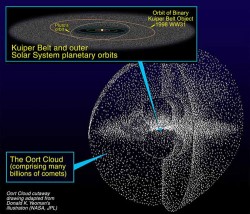

1. The Oort Cloud

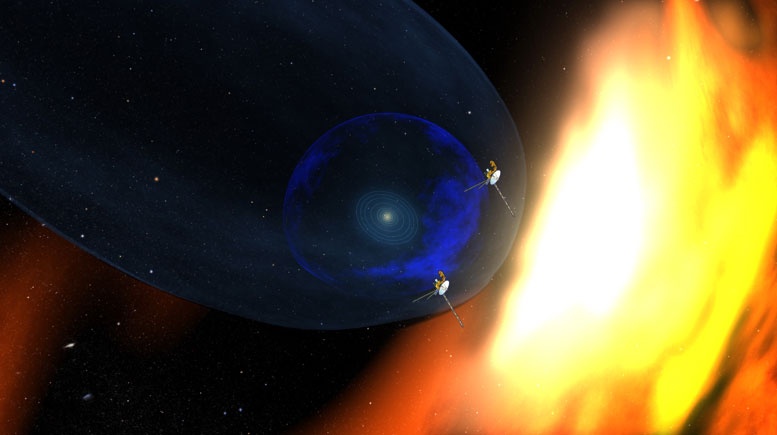

How do we know the Oort Cloud even exists? As far as Solar System mysteries go, the Pioneer anomaly is a tough act to follow, but the Oort cloud (in my view) is the biggest mystery of all. Why? We have never seen it, it is a hypothetical region of space.

At least with the Kuiper Belt, we can observe the large KBOs and we know where it is, but the Oort Cloud is too far away (if it really is out there). Firstly, the Oort Cloud is predicted to be over 50,000 AU from the Sun (that’s nearly a light year away), making it about 25% of the way toward our nearest stellar neighbour, Proxima Centauri. The Oort Cloud is therefore a very long way away. The outer reaches of the Oort Cloud is pretty much the edge of the Solar System, and at this distance, the billions of Oort Cloud objects are very loosely gravitationally bound to the Sun. They can therefore be dramatically influenced by the passage of other nearby stars. It is thought that Oort Cloud disruption can lead to icy bodies falling inward periodically, creating long-period comets (such as Halley’s comet).

In fact, this is the only reason why astronomers believe the Oort Cloud exists, it is the source of long-period icy comets which have highly eccentric orbits emanating regions out of the ecliptic plane. This also suggests that the cloud surrounds the Solar System and is not confined to a belt around the ecliptic.

So, the Oort Cloud appears to be out there, but we cannot directly observe it. In my books, that is the biggest mystery in the outermost region of our Solar System…