[/caption]

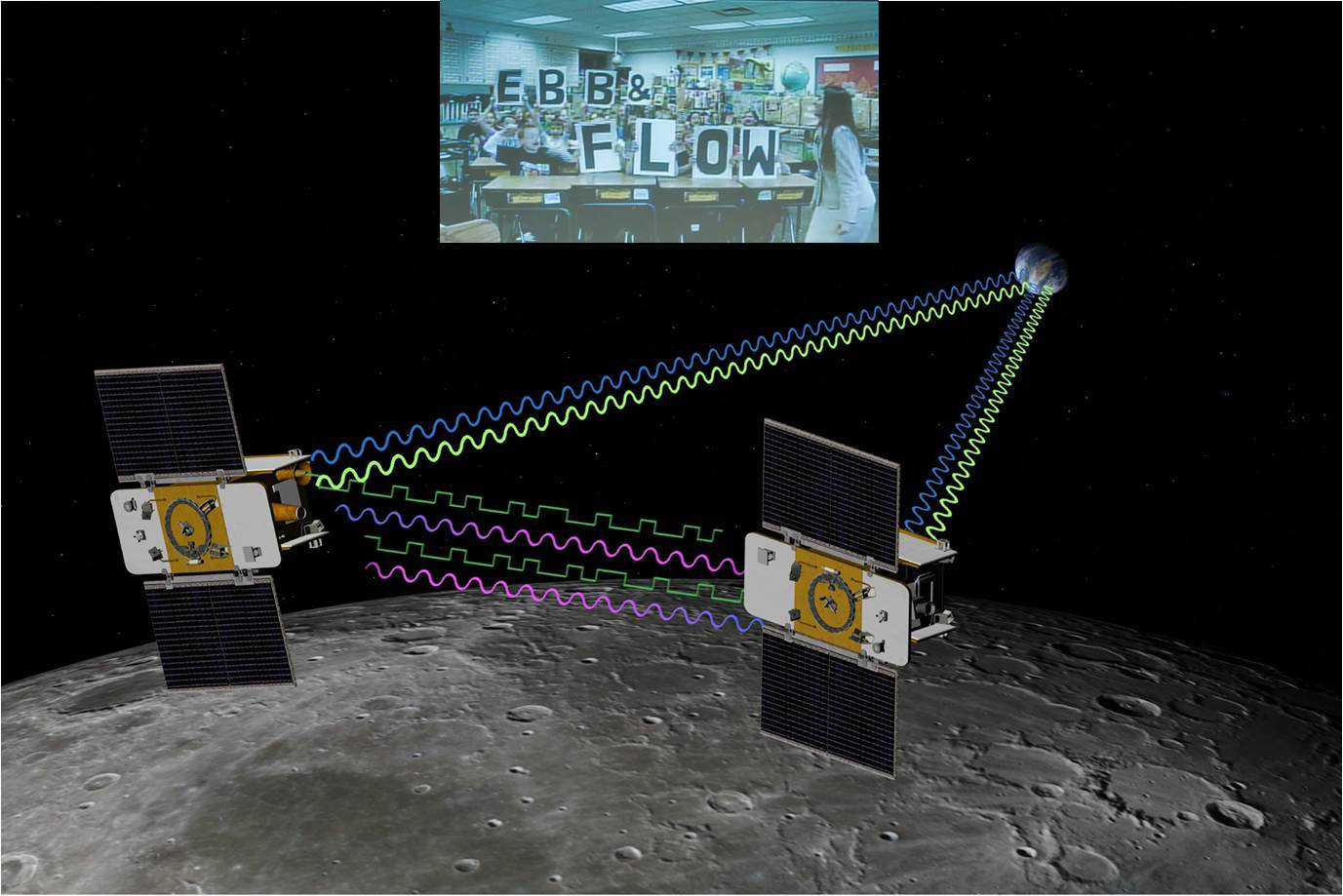

A classroom of America’s Youth from an elementary school in Bozeman, Montana submitted the stellar winning entry in NASA’s nationwide student essay contest to rename the twin GRAIL lunar probes that just achieved orbit around our Moon on New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day 2012

“Ebb” & “Flow” – are the dynamic duo’s official new names and were selected because they clearly illuminate the science goals of the gravity mapping spacecraft and how the Moon’s influence mightily affects Earth every day in a manner that’s easy for everyone to understand.

“The 28 students of Nina DiMauro’s class at the Emily Dickinson Elementary School have really hit the nail on the head,” said GRAIL principal investigator Prof. Maria Zuber of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass.

“We asked the youth of America to assist us in getting better names.”

“We chose Ebb and Flow because it’s the daily example of how the Moon’s gravity is working on the Earth,” said Zuber during a media briefing held today (Jan. 17) at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. The terms ebb and flow refer to the movement of the tides on Earth due to the gravitational pull from the Moon.

“We were really impressed that the students drew their inspiration by researching GRAIL and its goal of measuring gravity. Ebb and Flow truly capture the spirit and excitement of our mission.”

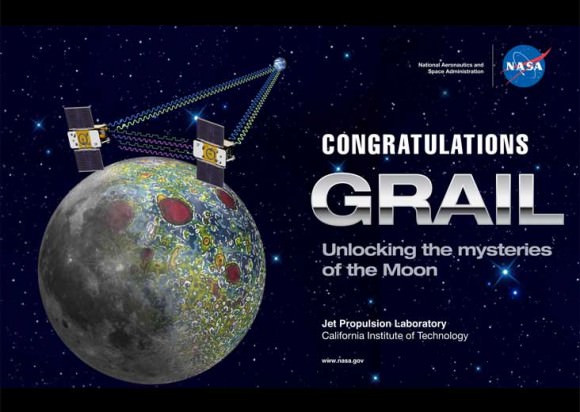

Ebb and Flow are flying in tandem around Earth’s only natural satellite, the first time such a feat has ever been attempted.

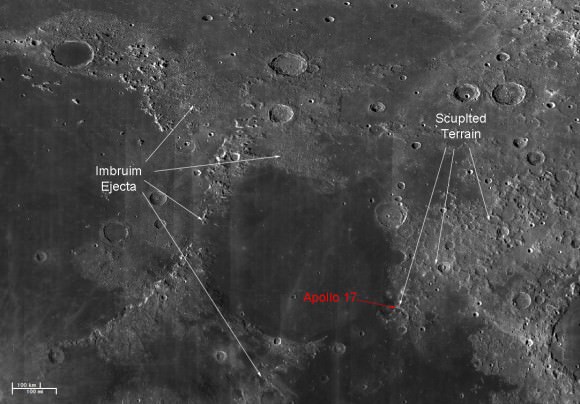

As they fly over mountains, craters and basins on the Moon, the spaceships will move back and forth in orbit in an “ebb and flow” like response to the changing lunar gravity field and transmit radio signals to precisely measure the variations to within 1 micron, the width of a red blood cell.

The breakthrough science expected from the mirror image twins will provide unprecedented insight into what lurks mysteriously hidden beneath the surface of our nearest neighbor and deep into the interior.

The winning names from the 4th Graders of Emily Dickinson Elementary School were chosen from essays submitted by nearly 900 classrooms across America with over 11,000 students from 45 states, Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia, Zuber explained.

The students themselves announced “Ebb” and “Flow” in a dramaric live broadcast televised on NASA TV via Skype.

“We are so thrilled that our names were chosen and excited to share this with you. We can’t believe we won! We are so honored. Thank you!” said Ms. DiMauro as the very enthusiastic students spelled out the names by holding up the individual letters one-by-one on big placards from their classroom desks in Montana.

Watch the 4th Grade Kids spell the names in this video!

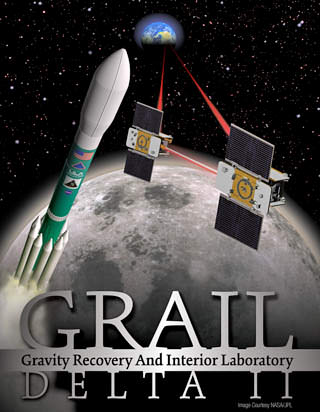

Until now the pair of probes went by the rather uninspiring monikers of GRAIL “A” and “B”. GRAIL stands for Gravity Recovery And Interior Laboratory.

The twin crafts’ new names were selected jointly by Prof. Zuber and Dr. Sally Ride, America’s first woman astronaut, and announced during today’s NASA briefing.

NASA’s naming competition was open to K-12 students who submitted pairs of names and a short essay to justified their suggestions.

“Ebb” and “Flow” (GRAIL A and GRAIL B) are the size of washing machines and were launched side by side atop a Delta II booster rocket on September 10, 2011 from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

They followed a circuitous 3.5 month low energy path to the Moon to minimize the fuel requirements and overall costs.

So far the probes have completed three burns of their main engines aimed at lowering and circularizing their initial highly elliptical orbits. The orbital period has also been reduced from 11.5 hours to just under 4 hours as of today.

“The science phase begins in early March,” said Zuber. At that time the twins will be flying in tandem at 55 kilometers (34 miles) altitude.

The GRAIL twins are also equipped with a very special camera dubbed MoonKAM (Moon Knowledge Acquired by Middle school students) whose purpose is to inspire kids to study science.

“GRAIL is NASA’s first planetary spacecraft mission carrying instruments entirely dedicated to education and public outreach,” explained Sally Ride. “Over 2100 classrooms have signed up so far to participate.”

Thousands of middle school students in grades five through eight will select target areas on the lunar surface and send requests for study to the GRAIL MoonKAM Mission Operations Center in San Diego which is managed by Dr. Ride in collaboration with undergraduate students at the University of California in San Diego.

By having their names selected, the 4th graders from Emily Dickinson Elementary have also won the prize to choose the first target on the Moon to photograph with the MoonKam cameras, said Ride.

Zuber notes that the first MoonKAM images will be snapped shortly after the 82 day science phase begins on March 8.

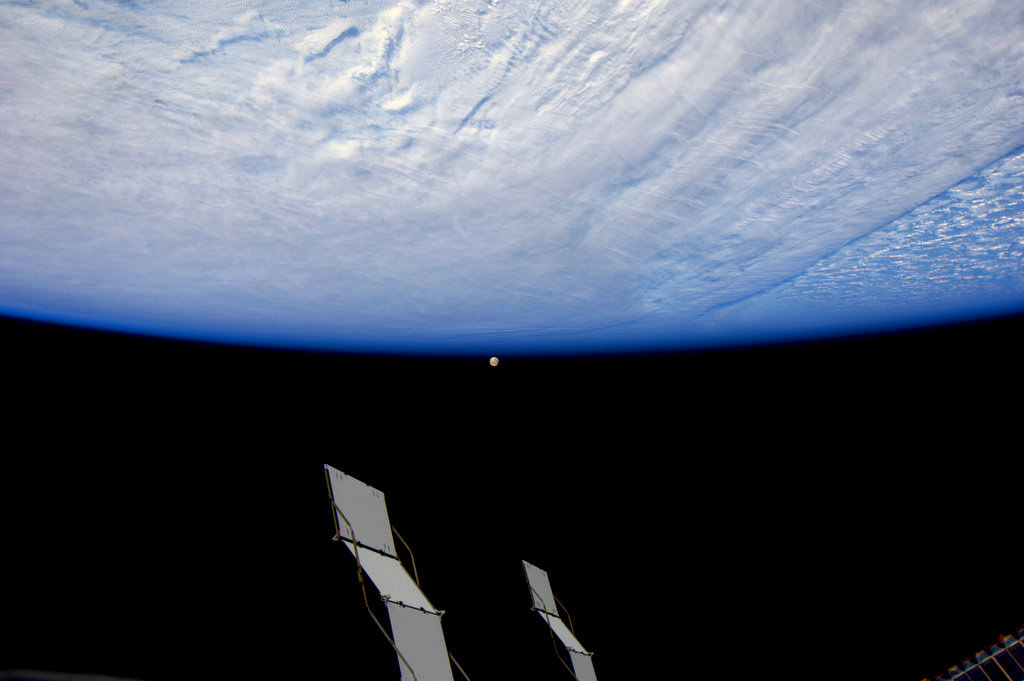

NASA’s twin GRAIL-A & GRAIL-B spacecraft are orbiting the Moon in this astrophoto taken on Jan. 2, 2012 shortly after successful Lunar Orbit Insertions on New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day 2012.

Credit: Ken Kremer

Read continuing features about GRAIL and the Moon by Ken Kremer here:

Dazzling Photos of the International Space Station Crossing the Moon!

Two new Moons join the Moon – GRAIL Twins Achieve New Year’s Orbits

First GRAIL Twin Enters Lunar Orbit – NASA’s New Year’s Gift to Science

2011: Top Stories from the Best Year Ever for NASA Planetary Science!

NASA’s Unprecedented Science Twins are GO to Orbit our Moon on New Year’s Eve

Student Alert: GRAIL Naming Contest – Essay Deadline November 11

GRAIL Lunar Blastoff Gallery

GRAIL Twins Awesome Launch Videos – A Journey to the Center of the Moon

NASA launches Twin Lunar Probes to Unravel Moons Core

GRAIL Unveiled for Lunar Science Trek — Launch Reset to Sept. 10

Last Delta II Rocket to Launch Extraordinary Journey to the Center of the Moon on Sept. 8

NASAs Lunar Mapping Duo Encapsulated and Ready for Sept. 8 Liftoff

GRAIL Lunar Twins Mated to Delta Rocket at Launch Pad

GRAIL Twins ready for NASA Science Expedition to the Moon: Photo Gallery