[/caption]

When President Kennedy promised America a lunar landing in 1961, he effectively set the Moon as the finish line in the space race. In the wake of his speech, NASA began scrambling to find a way to reach the Moon in advance of the Soviet Union, which at the time held a commanding lead in space. Apollo, already on the drawing board as an Earth orbiting program, was revised to reflect the lunar goal and Gemini was established as the interim program.

The pieces were in place; all NASA needed was a way to get to the Moon. Against this pressing background, two men proposed a desperate and direct mission to get an American on the Moon as quickly as possible.

The proposal came from two Bell Aerosystems Company employees. John M. Cord was a Project Engineer in the Advanced Design Division and Leonard M. Seale was a psychologist in charge of the Human Factors Division. At the Institute of Aerospace Sciences in Los Angeles in 1962, the pair unveiled their “One-Way Manned Space Mission” proposal.

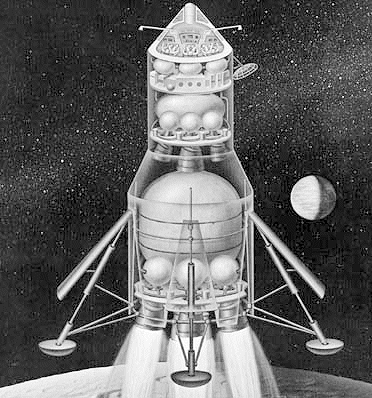

The plan called for a one-man spacecraft to follow a direct ascent path to the Moon. Ten feet wide and seven feet tall, the empty spacecraft weighed less than half the much smaller Mercury capsule. Inside, the astronaut would have enough water for 12 days, oxygen for 18 with a 12-day emergency reserve, a battery-powered suit and backpack, and all the tools and medical supplies he might need.

He would land on the Moon after a two-and-a-half day trip and have just under ten days to set up his habitat. As part of his payload, the astronaut would arrive with four cargo modules with pre-installed life support systems and a nuclear reactor to generate electrical power. Two mated modules would become his primary living quarters, while the others placed in caves or buried in rubble — a feature Cord and Seale assumed would dominate the lunar landscape — would provide a shelter from solar storms.

With his temporary home set up, he would wait a little over two years for another mission to come and collect him. Cord and Seale estimated that this mission could be launched as early as 1965, a year of expected minimal solar activity. Larger launch vehicles capable of sending the three-man Apollo spacecraft would be ready by 1967. The one-way spaceman would have a long but finite stay on the Moon.

This proposal was incredibly practical. Since the astronaut wouldn’t be launching from the lunar surface, he wouldn’t need to carry the necessary propellant. Since he would return to Earth in another spacecraft, his own spacecraft wouldn’t need a heavy heat shield or parachutes. The one-way mission was a light and efficient proposal.

But it was also dangerous. The proposal didn’t include any redundancies; the direct ascent path gave the astronaut no chance to abort his mission after launch. He would have to deal with any problems that arose knowing he wouldn’t be able to make a quick return home.

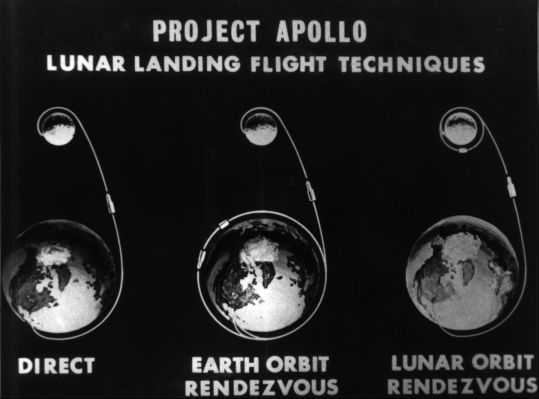

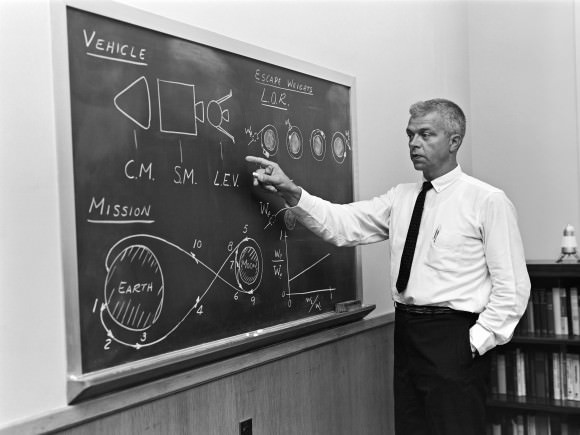

Luckily for the possible astronaut the proposal was never seriously considered. In July 1962, a few weeks after the one-way mission was proposed, NASA announced its selection of the more complicated but safer Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (LOR) mode for Apollo missions.

khj

khj

Wow. I thought the one-way to Mars missions were audacious.

The Mercury capsule is mentioned here, and I seem to recall there was a contingency for the landing craft to be a Mercury capsule outfitted with a descent stage that would lower the astronaut to the moon. The cargo craft with the habitat module would have landed nearby. I don’t think this was ever seriously considered as anything more than a desperate back up if the Saturn-Apollo system ran into serious technical problems and the Soviets appeared poised to make the lunar trip.

Thr Russians gave us a run for the money. If you look at

http://www.russianspaceweb.com/n1.html

you can get a sense of what they worked on. Under “spacecraft” on the left of the page you can see the intended lunar craft. The N1 launch vehicle exploded on test flight and the program went into a stall in early 1969.

LC

Nothing new under the Sun. Now I know where those one-way to Mars ideas originated.

@ lcrowell:

I remember an exhibition with a technical mockup of the USSR landing craft. It was unbelievably small.

But an article, probably of Teitel, showed how they ingeniously used space walks and modules (their specialty) to cut down on needed mass. It would have worked, if the massively redundant N1 had worked.*

Unfortunately the redundancy wasn’t partitioned into isolated elements like for example the ingenious V-1 rocket engine with its many small engine outlets into a central outlet. One malfunction could, and did recurrently, tip the whole top…

Btw, wtf do you use a 230 t payload N1 for? Where they planning for Mars too?

The 1968 movie ‘Countdown’ (starring James Caan, and based on the Hank Searls novel ‘The Pilgrim Project’) also explores this notion, using a modified Gemini spacecraft on a Lunar Module-like descent stage, to land one man near a previously launched shelter, as the Soviets attempt their first landing.

Still not as awesome as project A119

I’m glad America’s lunar legacy is the Apollo missions. Apollo sends a very positive and hopeful message. This does not.

Since those two men were so bold as to make that proposal, they should have been among the first ( on a very short list of ) candidates to have volunteered.

Now why in earthlight, would a suicide-mission astronaut need medical supplies?

Regarding the inherent dangers of a one-way mission: it really only made a difference as to when, and how, the self-sacrificing space-voyager would die — quickly, on lunar day one, crashing and burning, or slowly, on day 12 by asphyxiation ( either way, his medical kit would not have been of much value ).

The mission wasn’t strictly one-way: as the article notes, a future mission would collect the astronaut two years later.

Thanks for the clarification.

There were a few lines that confused me — one way or not one way. It just came into focus: I densely missed the two-way aspect.

Interesting “Edit”: Long and expensive, indeed, and probably requiring back-ups of back-ups, and redundancies of redundancies ( adding to the astronomical costs ) — in value of human life. Equation: Cost vs.Science return x value of human life, squared[?] with risks and dangers. To venture forth over a great ocean expanse or no, to risk treasure and life for a new, far-distant landfall shore? ( Or will it be just another “Cold” race among the nations? )

Well, anyway, you explained the need for a “medical” kit!

Well, there are always plenty of people willing to go on even the most dangerous missions, given the opportunity – this has been true throughout the ages. Astronauts downplay the risks to themselves, because they see the upshots: the ultimate adventure and a place in history.

Here’s how I see it: the real risk that a disaster presents is not so much the loss of astronaut life, tragic as it is, but the consequences of that loss: for politicans and program-managers, it could be an embarrassing and vilifying career-ender. I think that politicians and program managers, for this reason (along with the horrible guilt they’d no doubt experience), are much less willing to put astronauts in danger than the astronauts themselves are willing to be in. That might be why this moon mission never happened.

“No pessimist ever discovered the secret of the stars, or sailed to an uncharted land, or opened a new doorway for the human spirit.” – Helen Keller (1880–1968), “American author and educator who was blind and deaf” (Encyclopedia Britannica). One who embarked – through helping hands – on an extraordinary journey from darkness to light!

I’m not sure if my comment got where it needed to go – received an odd error message – so here goes again:

I consider this in considerably greater detail here: http://beyondapollo.blogspot.com/2010/09/one-way-space-man-1962.html

I also use the original artwork, so you can see what Cord & Seale had in mind, and I discuss THE PILGRIM PROJECT, COUNTDOWN, and public perception of some recent one-way Mars mission concepts.

My entire blog is devoted to space missions that didn’t happen.

David S. F. Portree