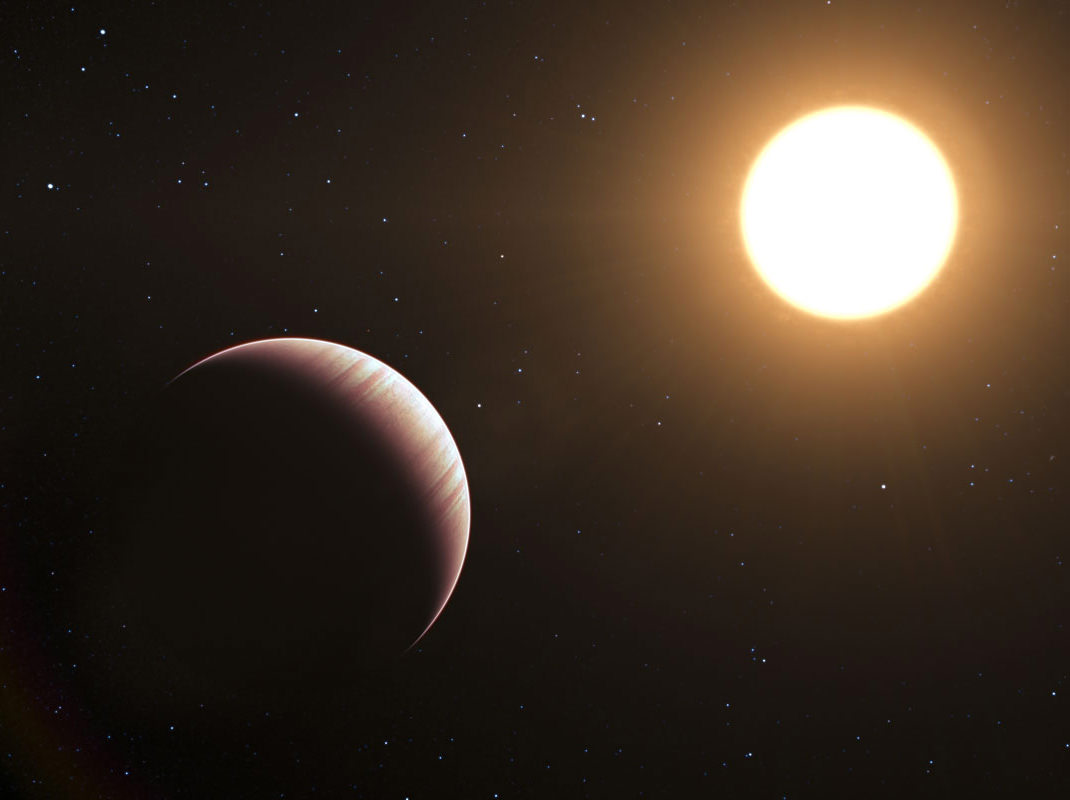

Dwarf star HD 40307 is now thought to host at least 6 exoplanet candidates… one of them well within its habitable zone. (G. Anglada/Celestia)

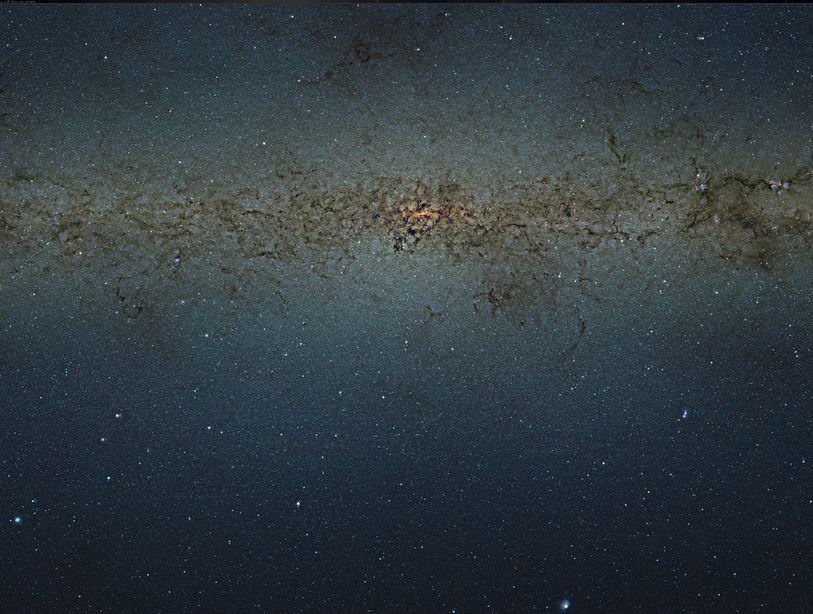

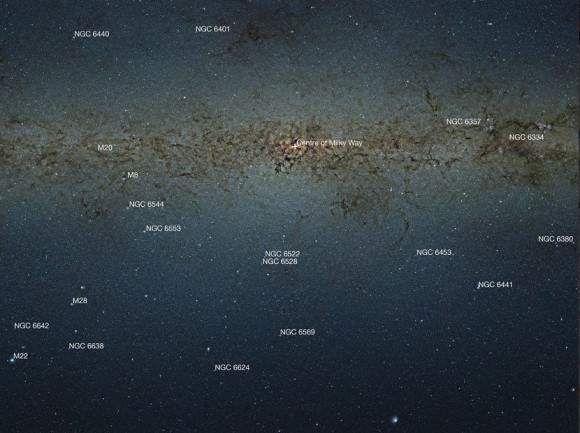

Located 43 light-years away in the southern constellation Pictor, the orange-colored dwarf star HD 40307 has previously been found to hold three “super-Earth” exoplanets in close orbit. Now, a team of researchers poring over data from ESO’s HARPS planet-hunting instrument are suggesting that there are likely at least six super-Earth exoplanets orbiting HD 40307 — with one of them appearing to be tucked neatly into the star’s water-friendly “Goldilocks” zone.

HARPS (High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher) on ESO’s La Silla 3.6m telescope is a dedicated exoplanet hunter, able to detect the oh-so-slight wobble of a star caused by the gravitational tug of orbiting planets. Led by Mikko Tuomi of the UK’s University of Hertfordshire Centre for Astrophysics Research, a team of researchers reviewed publicly-available data from HARPS and has identified what seems to be three new exoplanets in the HD 40307 systems. The candidates, designated with the letters e, f, and g, all appear to be “super Earth” worlds… but the last one, HD 40307 g, is what’s getting people excited, as the team has calculated it to be orbiting well within the region where liquid water could exist on its surface — this particular star’s habitable zone.

In addition, HD 40307 g is located far enough away from its star to likely not be tidally locked, according to the team’s paper. This means it wouldn’t have one side subject to constant heat and radiation while its other “far side” remains cold and dark, thus avoiding the intense variations in global climate, weather and winds that would come as a result.

“The star HD 40307, is a perfectly quiet old dwarf star, so there is no reason why such a planet could not sustain an Earth-like climate.”

– Guillem Anglada-Escudé, co-author.

“If the signal corresponding to HD 40307 g is a genuine Doppler signal of planetary origin, this candidate planet might be capable of supporting liquid water on its surface according to the current definition of the liquid water habitable zone around a star and is not likely to suffer from tidal locking.” (Tuomi et al.)

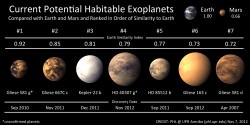

If HD 40307 g is indeed confirmed, it may very well get onto the official short list of potentially habitable worlds outside our Solar System — although those others are quite a bit closer to the mass of our own planet.

UPDATE: HD 40307 g has been added to the Planetary Habitability Laboratory’s Habitable Exoplanets Catalog, maintained by the PHL at the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo. It’s now in 4th place of top exoplanets of interest based on similarity to Earth. According to Professor Abel Mendez Torres of the PHL, “Average temperatures might be near 9°C (48°F) assuming a similar scaled-up terrestrial atmosphere. It might also experience strong seasonal surface temperature shifts between -17° to 52°C (1.4° to 126°F) due to its orbital eccentricity. Nevertheless, these extremes are tolerable by most complex life, as we know it.” (Read more here.)

UPDATE: HD 40307 g has been added to the Planetary Habitability Laboratory’s Habitable Exoplanets Catalog, maintained by the PHL at the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo. It’s now in 4th place of top exoplanets of interest based on similarity to Earth. According to Professor Abel Mendez Torres of the PHL, “Average temperatures might be near 9°C (48°F) assuming a similar scaled-up terrestrial atmosphere. It might also experience strong seasonal surface temperature shifts between -17° to 52°C (1.4° to 126°F) due to its orbital eccentricity. Nevertheless, these extremes are tolerable by most complex life, as we know it.” (Read more here.)

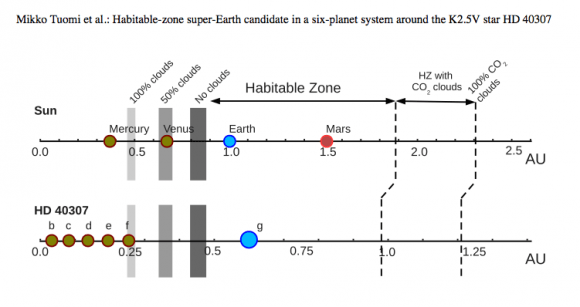

While the other planetary candidates in the HD 40307 system are positioned much more closely to the star, with b, c, d, and e within or at the equivalent orbital distance of Mercury, g appears to be in the star’s liquid-water habitable zone, orbiting at 0.6 AU in an approximately 200-day-long orbit. At this distance the estimated 7-Earth-mass exoplanet receives around 62-67% of the radiation that Earth gets from the Sun.

Representation of the liquid water habitable zone around HD 40307 compared to our Solar System (Tuomi et al., from the team’s paper.)

Although news like this is exciting, as we’re always eagerly anticipating the announcement of a true, terrestrial Earthlike world that could be host to life as we know it, it’s important to remember that HD 40307 g is still a candidate — more observations are needed to not only confirm its existence but also to find out exactly what kind of planet it may be.

“A more detailed characterization of this candidate is very unlikely using ground based studies because it is very unlikely [sic] to transit the star, and a direct imaging mission seems the most promising way of learning more about its possible atmosphere and life-hosting capabilities,” the team reports.

Read: How Well Can Astronomers Study Exoplanet Atmospheres?

Still, just finding potential Earth-sized worlds in a system like HD 40307’s is a big deal for planetary scientists. This system is not like ours, yet somewhat similar planets have still formed… that in itself is a clue to what else may be out there.

“The planetary system around HD 40307 has an architecture radically different from that of the solar system… which indicates that a wide variety of formation histories might allow the emergence of roughly Earth-mass objects in the habitable zones of stars.”

The team’s paper will be published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. http://arxiv.org/pdf/1211.1617v1.pdf

Another researcher on the team, Guillem Anglada-Escudé of Germany’s Universität Göttingen, assembled this tour of the HD 40307 system (not including g) via Celestia.

Inset image: current potentially habitable exoplanets. Credit: PHL @ UPR Arecibo.