Scientists have determined a giant gas cloud is on a collision course with the black hole in the center of our galaxy, and the two will be close enough by mid-2013 to provide a unique opportunity to observe how a super massive black hole sucks in material, in real time. This will give astronomers more information on how matter behaves near a black hole.

“The next few years will be really fantastic and exciting because we are probing new territory,” said Reinhard Genzel, leading a team from the ESO in observations with the Very Large Telescope. “Here this cloud comes in gets disrupted and now it will begin to interact with the hot gas right around the black hole. We have never seen this before.”

By June of 2013, the gas cloud is expected to be just 36 light-hours (equivalent to 40,000,000,000 km) away from our galaxy’s black hole, which is extremely close in astronomical terms.

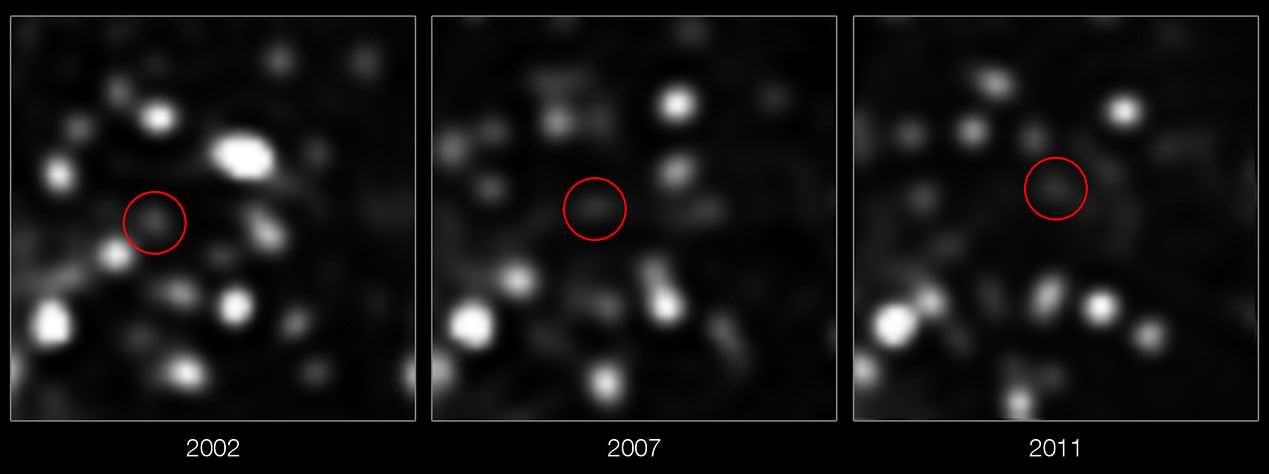

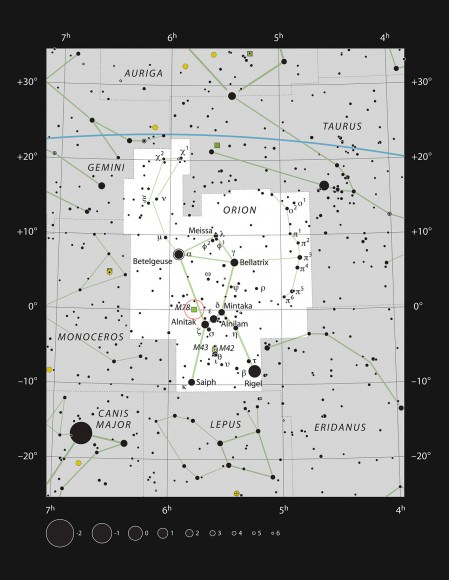

Astronomers have determined the speed of the gas cloud has increased, doubling over the past seven years, and is now reaching more than 8 million km per hour. The cloud is estimated to be three times the mass of Earth and the density of the cloud is much higher than that of the hot gas surrounding black hole. But the black hole has a tremendous gravitational force, and so the gas cloud will fall into the direction of the black hole, be elongated and stretched and look like spaghetti, said Stefan Gillessen, astrophysicist at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Munich, Germany, who has been observing our galaxy’s black hole, known as Sagittarius A* (or Sgr A*), for 20 years.

“So far there were only two stars that came that close to Sagittarius A*,” Gillessen said. “They passed unharmed, but this time will be different: the gas cloud will be completely ripped apart by the tidal forces of the black hole.”

Watch a video of observations of the cloud for the past 10 years:

No one really knows how the collision will unfold, but the cloud’s edges have already started to shred and it is expected to break up completely over the coming months. As the time of actual collision approaches, the cloud is expected to get much hotter and will probably start to emit X-rays as a result of the interaction with the black hole.

Although direct observations of black holes are impossible, as they do not emit light or matter, astronomers can identify a black hole indirectly due to the gravitational forces observed in their vicinity.

A black hole is what remains after a super massive star dies. When the “fuel” of a star runs low, it will first swell and then collapse to a dense core. If this remnant core has more than three times the mass of our Sun, it will transform to a black hole. So-called super massive black holes are the largest type of black holes, as their mass equals hundreds of thousands to a billion times the mass of our Sun.

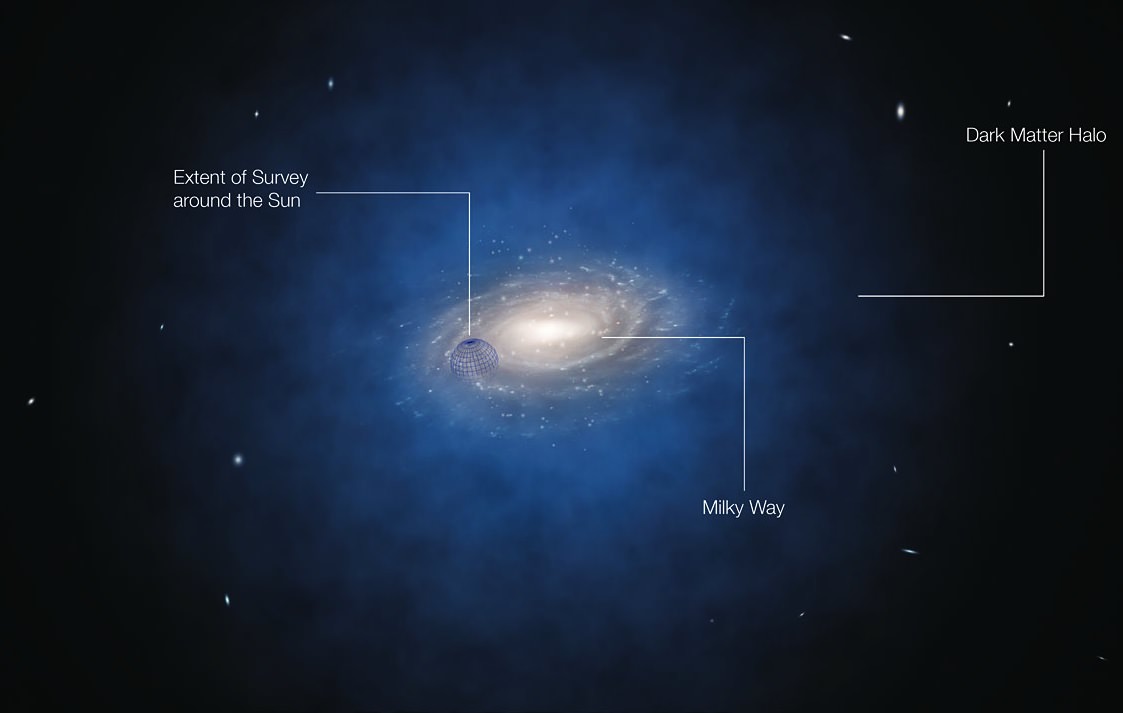

Black holes are thought to be at the center of all galaxies, but their origin is not fully understood and astrophysicists can only speculate as to what happens inside them. And so this upcoming collision just 27,000 light years away will likely provide new insights on the behavior of black holes.

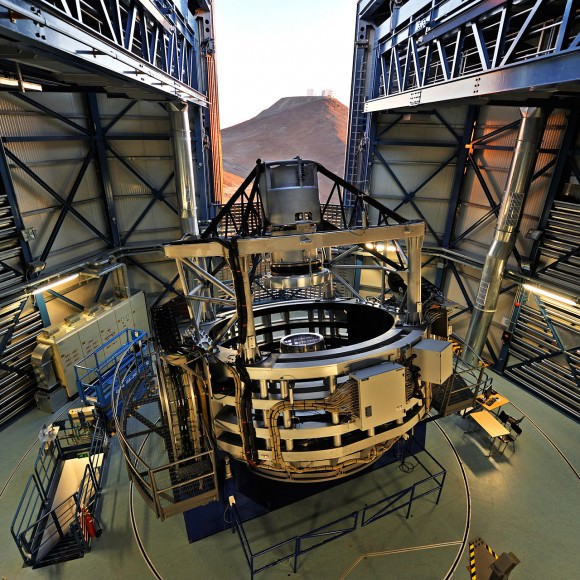

Lead image caption: Images taken over the last decade using the NACO instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope show the motion of a cloud of gas that is falling towards the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. This is the first time ever that the approach of such a doomed cloud to a supermassive black hole has been observed and it is expected to break up completely during 2013. Credit: ESO/MPE

Read our previous article about this topic, from Dec. 2011.

Source: European Research Media Center