Note: To celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Hubble Space Telescope, for ten days, Universe Today will feature highlights from two year slices of the life of the Hubble, focusing on its achievements as an astronomical observatory. Today’s article looks at the period April 1996 to April 1998.

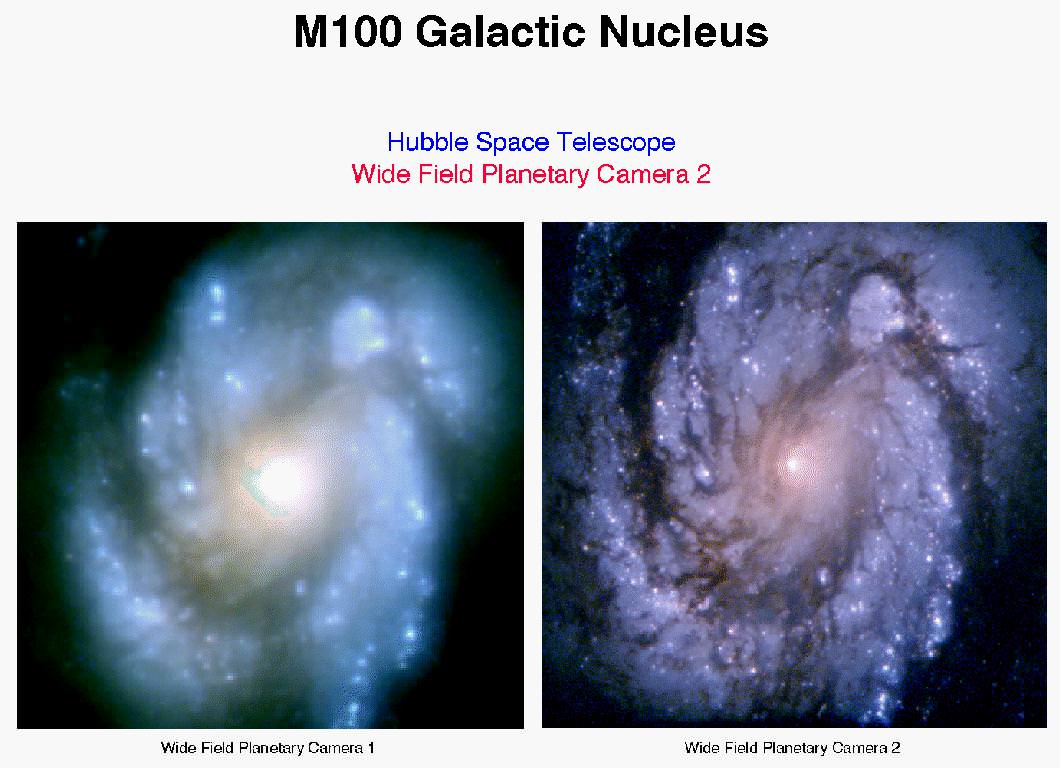

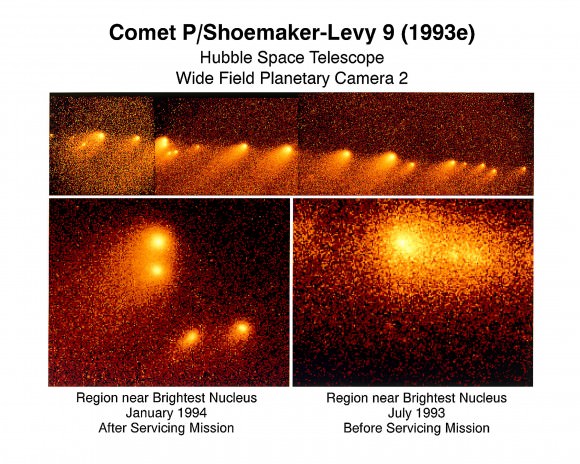

The ability of the Hubble Space Telescope to be serviced by astronauts, using a space shuttle as a platform, is one of its design features. This proved its worth very early, with the first servicing mission installing COSTAR. The second such mission – a ten day effort with Discovery as the workhorse – took place in February 1997; two new instruments were installed (and two removed), the Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS) and the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS), and many other, smaller, upgrades and repairs made.

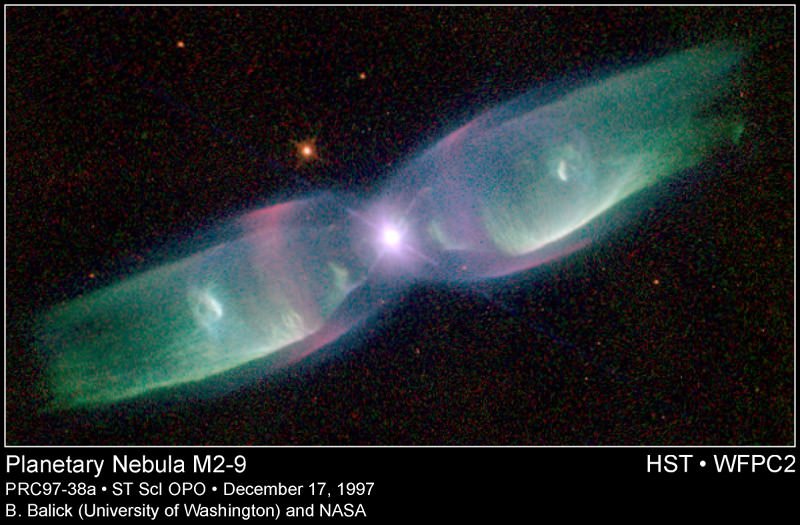

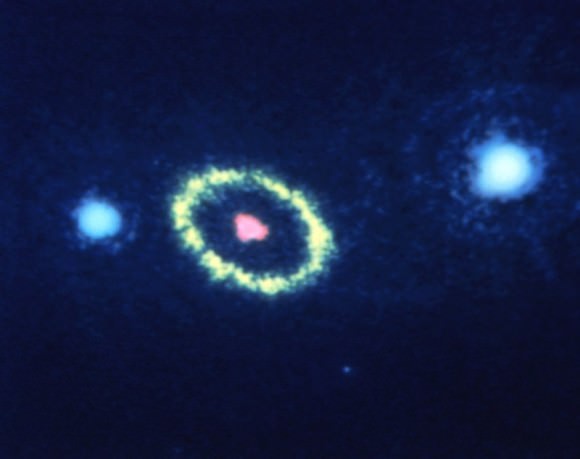

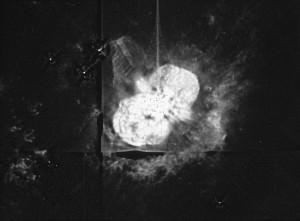

Yesterday’s article featured the Pillars of Creation; today’s captures the beauty of a star’s death.

[/caption]

How does the Hubble work? Who runs it? The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) is responsible for the scientific operation of Hubble as an international observatory; it has a combined staff of approximately 500, of whom approximately 100 are PhDs. Among the prime tasks of the STScI are the selection of the Hubble observing proposals, their execution, the scientific monitoring of the telescope and its instruments and the archiving and distribution of the Hubble observations.

The Space Telescope-European Coordinating Facility (ST-ECF) offers support for the preparation of Hubble observing proposals and the scientific analysis of observations. It also operates the Hubble Science Archive, which makes data available to the astronomical community via the Internet.

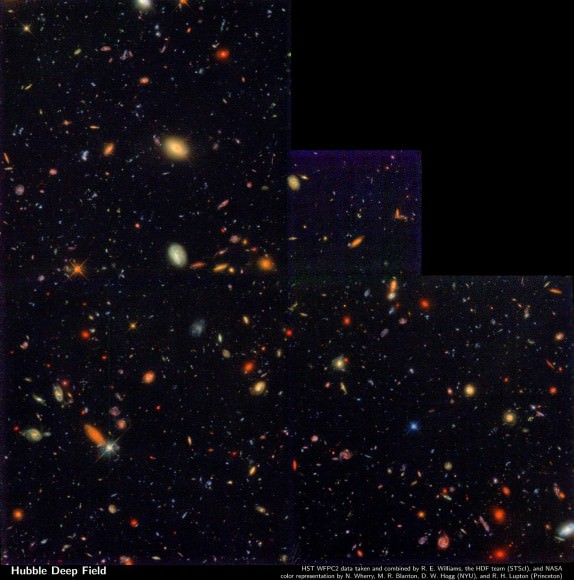

With the exception of observations like the Hubble Deep Field – which are available for immediate release – the data from Hubble observations are the exclusive property of the observers for one year, after which all scientific data are made available to anyone and everyone, via the internet. And guess what? Thousands of papers have been published, using such freely available data!

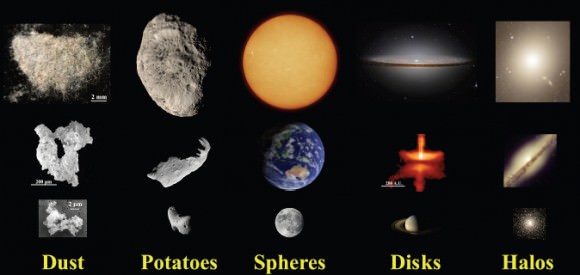

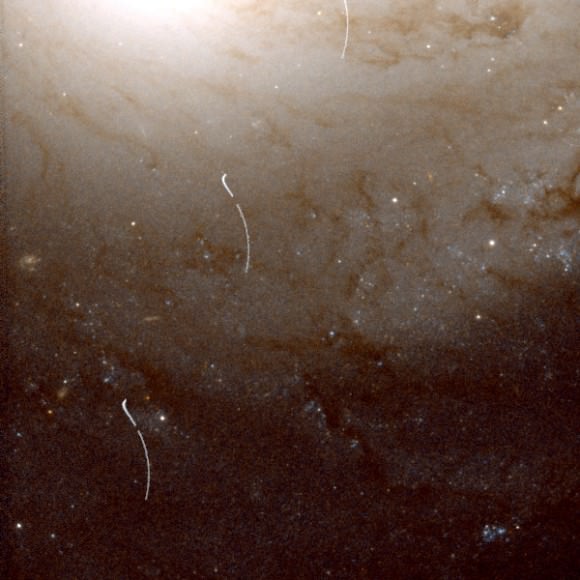

One example of the tremendous value of the Hubble archive is all the asteroids it inadvertently images; because of the Hubble’s sensitivity, motion, and resolution, the orbits of many of these can be determined from just the serendipitous images (discoveries made by ground-based telescopes usually require follow-up images days apart). And yes, many papers have been written, based on these images, “Asteroid Trails in Hubble Space Telescope” for example.

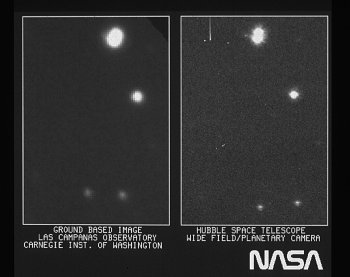

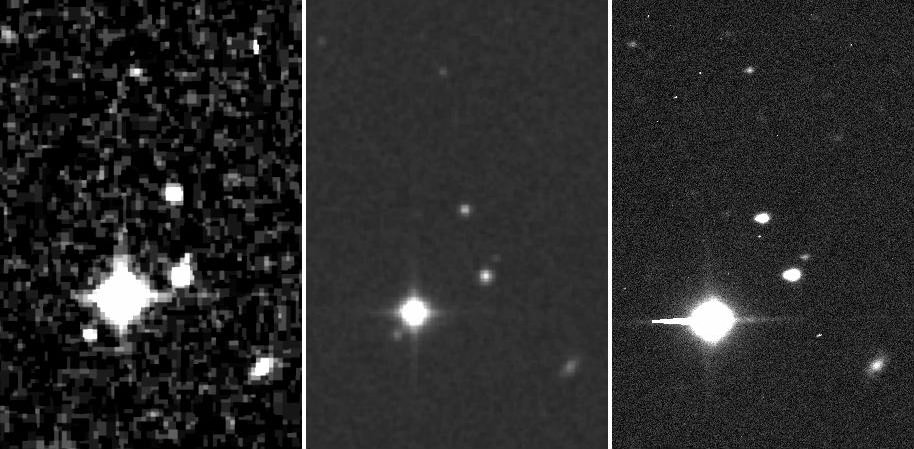

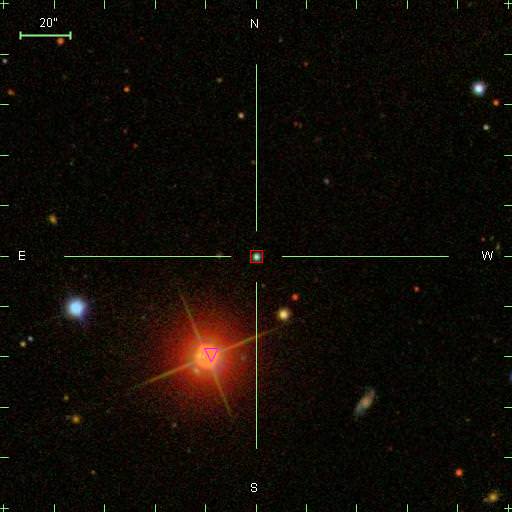

Sometimes something happens in the sky and you want to point powerful telescopes at it, quickly, before it disappears. By far the most interesting yet fleeting ‘something’ is gamma-ray bursts (GRBs). Although known for decades, none had been seen in any other electromagnetic waveband … until February 28, 1997. Right after its servicing mission, Hubble caught the afterglow of GRB 970228, located in very distant galaxy. A milestone in astronomy.

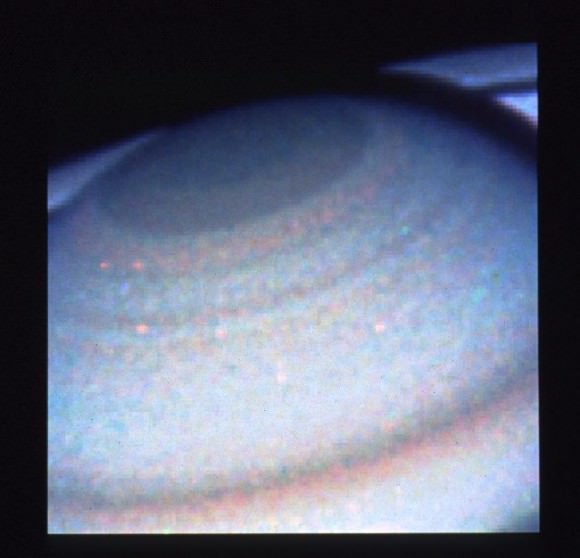

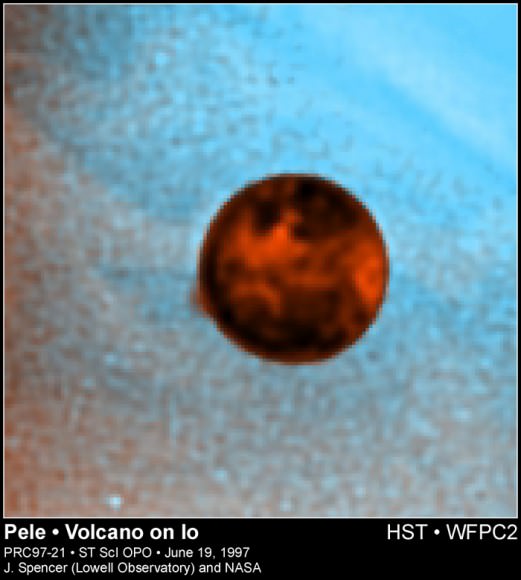

Volcanoes, active ones, were discovered on Io, by accident, in 1979, as volcanic plumes rising above the limb. Who could have imagined that such plumes would be imaged not twenty years later, from low-Earth orbit, with Jupiter as the backdrop?

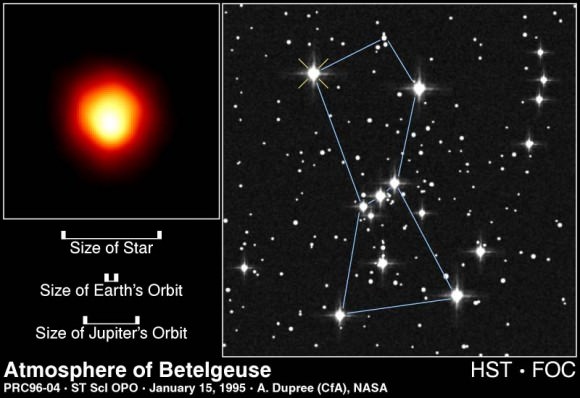

In 1920 Betelgeuse’s diameter was estimated, using a 6 meter interferometer mounted on the front of the 100-inch Mount Wilson telescope. In 1996, the Hubble made a direct observation of Betelgeuse, resolving it; only the second star to have ever been seen as anything but a point of light (what was the first?).

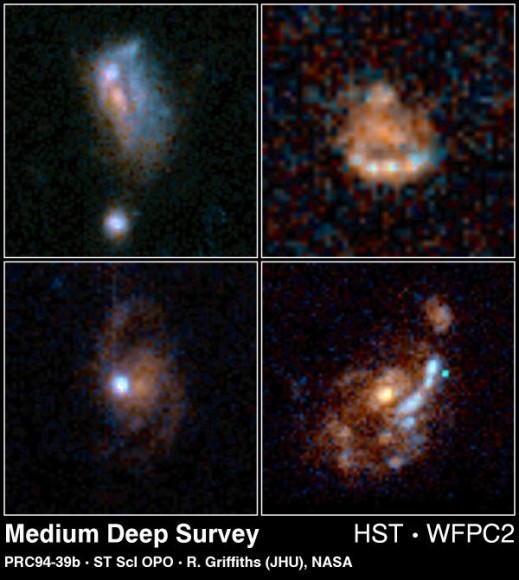

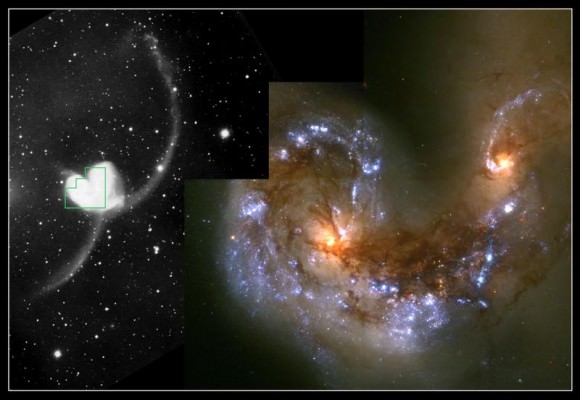

The Antennae galaxies, NGC 4038/NGC 4039, are not only highly photogenic (how many amateurs count their snaps of these among their most prized?), but great natural laboratories for studying galaxy collisions, star formation, etc. Hubble’s 1997 images provided the basis for hundreds of papers.

Tomorrow: 1998 and 1999.

Previous articles:

Hubble’s 20 Years: Now We Are Six

Hubble’s 20 Years: Time for 20/20 Vision

Hubble: It Was Twenty Years Ago Today

Sources: HubbleSite, European Homepage for the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, The SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System