[/caption]

When I tell people I majored in astronomy, the general reaction is one of shock and awe. Although people don’t realize just how much physics it is (which scares them even more when they found out), they’re still impressed that anyone would choose to major in a physical science. Quite often, I’m asked the question, “Why did you choose that major?”

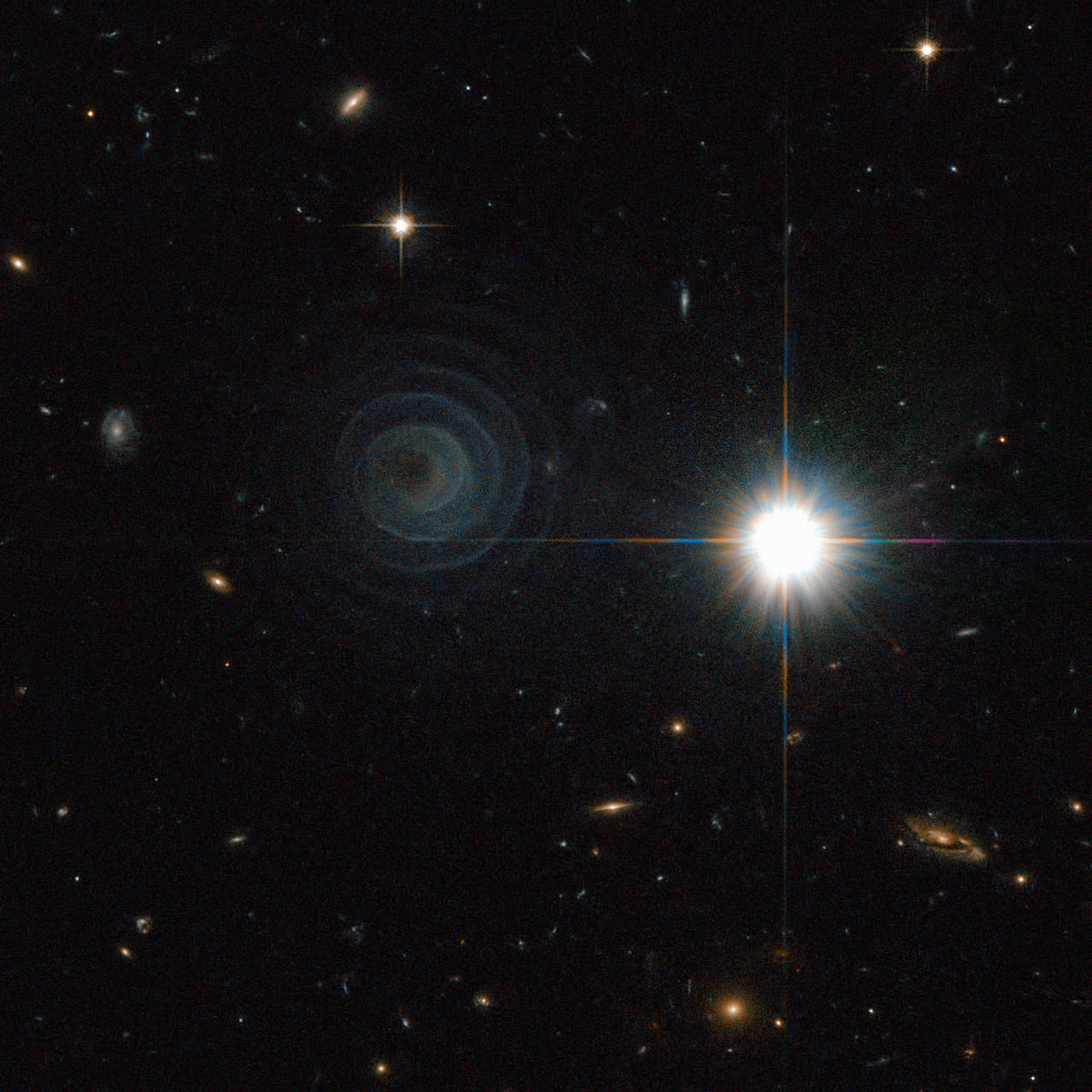

Only somewhat jokingly, I reply, “Because it’s pretty.” For what reasons would we explore something if we did not find some sort of beauty in it? This answer also tends to steer potential follow up questions to topics of images they’ve seen and away from topics from half-heard stories about black holes from sci-fi movies.

The topic of aesthetics in astronomy is one I’ve used here for my own devices, but a new study explores how we view astronomical images and what sorts of information people, both expert and amateur, take from them.

The study was conducted by a group formed in 2008 known as The Aesthetics and Astronomy Group. It is comprised of astrophysicists, astronomy image development professionals, educators, and specialists in the aesthetic and cognitive perception of images. The group asked to questions to guide their study:

- How much do variations in presentation of color, explanatory text, and illustrative scales affect comprehension of, aesthetic attractiveness, and time spent looking at deep space imagery?

- How do novices differ from experts in terms of how they look at astronomical images?

Data to answer this question was taken from two groups; The first was an online survey taken by volunteers from solicitations on various astronomy websites and included 8866 respondents. The second group was comprised of four focus groups held at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

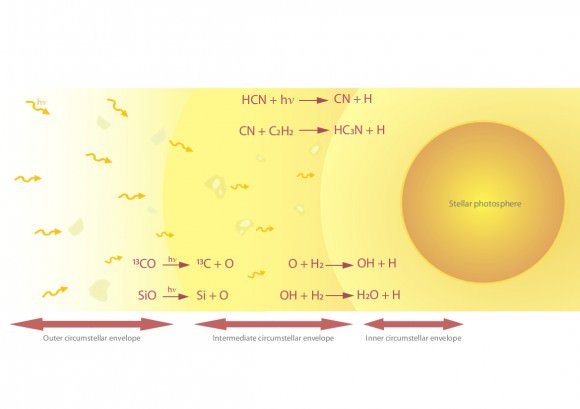

To analyze how viewers viewed color, the web study contained two pictures of the elliptical galaxy NGC 4696. The images were identical except for the colors chosen to represent different temperatures. In one image, red was chosen to represent hot regions and blue for cold regions. In the other version, the color scheme was reversed. A slight majority (53.3% to 46.7%) responded saying they preferred the version in which blue was assigned to be the hotter color. When asked which image they thought was the “hotter” image, 71.5% responded that the red image was hotter. Since astronomical images are often assigned with blue as the hotter color (since hotter objects emit shorter wavelength light which is towards the blue end of the visible spectrum), this suggests that the public’s perception of such images is likely reversed.

A second image for the web group divided the participants into 4 groups in which an image of a supernova remnant was shown with or without foreground stars and with or without a descriptive caption. When asked to rate the attractiveness, participants rated the one with text slightly higher (7.96 to 7.60 on a 10 point scale). Not surprisingly, those that viewed the versions of the image with captions were more likely to be able to correctly identify the object in the image. Additionally, the version of the image with stars was also more often identified correctly, even without captions, suggesting that the appearance of stars provides important context. Another question for this image also asked the size in comparison to the Earth, Solar System, and Galaxy. Although the caption gave the scale of the SNR in lightyears, the portion that viewed the caption did not fare better when asked to identify the size revealing such information is beyond the limit of usefulness.

The next portion showed an image of the Whirlpool galaxy, M51 and contained either, no text, a standard blurb, a narrative blurb, or a sectionized caption with questions as headers. Taking into consideration the time spent reading the captions, the team found that those with text spent more time viewing the image suggesting that accompanying text encourages viewers to take a second look at the image itself. The version with a narrative caption prompted the most extra time.

Another set of images explored the use of scales by superimposing circles representing the Earth, a circle of 300 miles, both, or neither onto an image of spicules on the Sun’s surface, with or without text. Predictably, those with scales and text were viewed longer and the image with both scales was viewed the longest and had the best responses on a true/false quiz over the information given by the image.

When comparing self-identified experts to novices, the study found that both viewed uncaptioned images for similar lengths of time, but for images with text, novices spent an additional 15 seconds reviewing the image when compared to experts. Differences between styles of presenting text (short blurb, narrative, or question headed), novices preferred the ones in which topics were introduced with questions, whereas experts rated all similarly which suggested they don’t care how the information is given, so long as it’s present.

The focus groups were given similar images, but were prompted for free responses in discussions.

<

p style=”padding-left: 30px;”>[T]he non-professionals wanted to know what the colors represented, how the images were made, whether the images were composites from different satellites, and what various areas of the images were. They wanted to know if M101 could be seen with a home telescope, binoculars, or the naked eye.

Additionally, they were also interested in historical context and insights from what professional astronomers found interesting about the images.

Professionals, on the other hand, responded with a general pattern of “I want to know who made this image and what it was that they were trying to convey. I want to judge whether this image is doing a good job of telling me what it is they

wanted me to get out of this.” Eventually, they discussed the aesthetic nature of the images which reveals that “novices … work from aesthetics to science, and for astrophysicists … work from science to aesthetics.”

Overall, the study found an eager public audience that was eager to learn to view the images as not just pretty pictures, but scientific data. It suggested that a conversational tone that worked up to technical language worked best. These findings can be used to improve communication of scientific objectives in museums, astrophotography sections of observatories, and even in presentation of astronomical images and personal conversation.