[/caption]

From the Spitzer website:

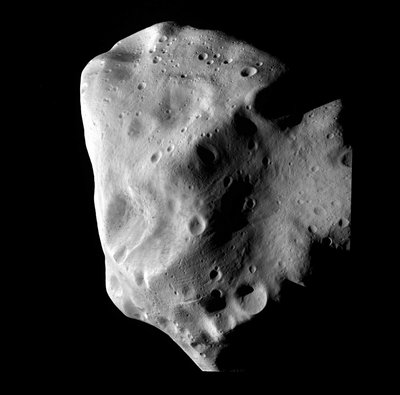

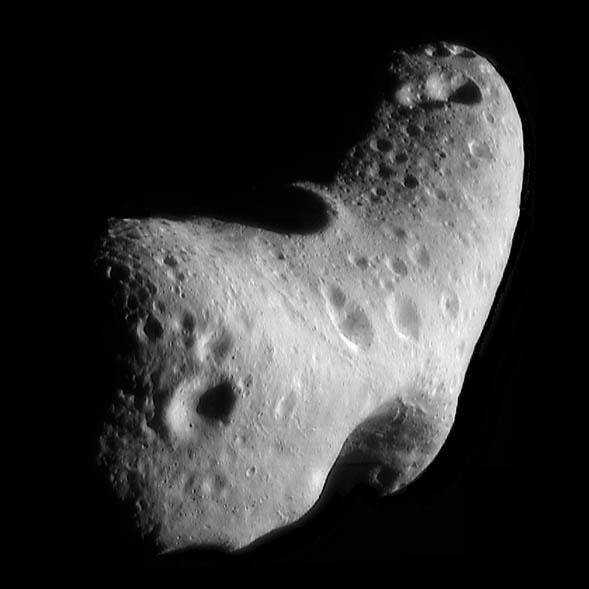

New research from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope reveals that asteroids somewhat near Earth, termed near-Earth objects, are a mixed bunch, with a surprisingly wide array of compositions. Like a piñata filled with everything from chocolates to fruity candies, these asteroids come in assorted colors and compositions. Some are dark and dull; others are shiny and bright. The Spitzer observations of 100 known near-Earth asteroids demonstrate that the objects’ diversity is greater than previously thought.

The findings are helping astronomers better understand near-Earth objects as a whole — a population whose physical properties are not well known.

“These rocks are teaching us about the places they come from,” said David Trilling of Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, lead author of a new paper on the research appearing in the September issue of Astronomical Journal. “It’s like studying pebbles in a streambed to learn about the mountains they tumbled down.”

After nearly six years of operation, in May 2009, Spitzer used up the liquid coolant needed to chill its infrared detectors. It is now operating in a so-called “warm” mode (the actual temperature is still quite cold at 30 Kelvin, or minus 406 degrees Fahrenheit). Two of Spitzer’s infrared channels, the shortest-wavelength detectors on the observatory, are working perfectly.

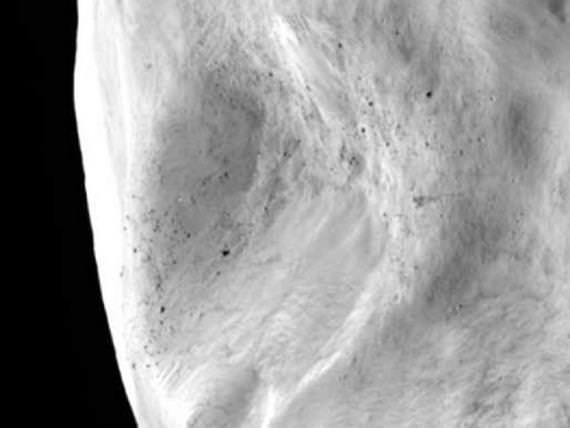

One of the mission’s new “warm” programs is to survey about 700 near-Earth objects, cataloging their individual traits. By observing in infrared, Spitzer is helping to gather more accurate estimates of asteroids’ compositions and sizes than what is possible with visible light alone. Visible-light observations of an asteroid won’t differentiate between an asteroid that is big and dark, or small and light. Both rocks would reflect the same amount of visible sunlight. Infrared data provide a read on the object’s temperature, which then tells an astronomer more about the actual size and composition. A big, dark rock has a higher temperature than a small, light one because it absorbs more sunlight.

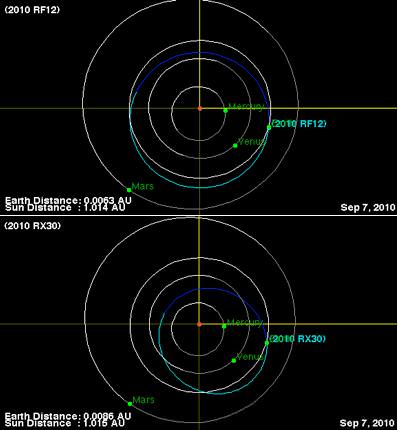

Trilling and his team have analyzed preliminary data on 100 near-Earth asteroids so far. They plan to observe 600 more over the next year. There are roughly 7,000 known near-Earth objects out of a population expected to number in the tens to hundreds of thousands.

“Very little is known about the physical characteristics of the near-Earth population,” said Trilling. “Our data will tell us more about the population, and how it changes from one object to the next. This information could be used to help plan possible future space missions to study a near-Earth object.”

The data show that some of the smaller objects have surprisingly high albedos (an albedo is a measurement of how much sunlight an object reflects). Since asteroid surfaces become darker with time due to exposure to solar radiation, the presence of lighter, brighter surfaces for some asteroids may indicate that they are relatively young. This is evidence for the continuing evolution of the near-Earth object population.

In addition, the fact that the asteroids observed so far have a greater degree of diversity than expected indicates that they might have different origins. Some might come from the main belt between Mars and Jupiter, and others could come from farther out in the solar system. This diversity also suggests that the materials that went into making the asteroids — the same materials that make up our planets — were probably mixed together like a big solar-system soup very early in its history.

The research complements that of NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, an all-sky infrared survey mission also up in space now. WISE has already observed more than 430 near-Earth objects — of these, more than 110 are newly discovered.

In the future, both Spitzer and WISE will tell us even more about the “flavors” of near-Earth objects. This could reveal new clues about how the cosmic objects might have dotted our young planet with water and organics — ingredients needed to kick-start life.