[/caption]

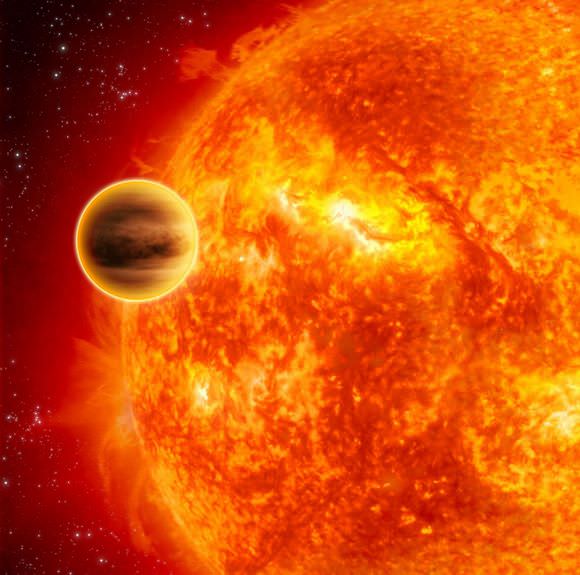

The large black holes that reside at the center of galaxies can be hungry beasts. As dust and gas are forced into the vicinity around the black holes, it crowds up and jostles together, emitting lots of heat and light. But what forces that gas and dust the last few light years into the maw of these supermassive black holes?

It has been theorized that mergers between galaxies disturbs the gas and dust in a galaxy, and forces the matter into the immediate neighborhood of the black hole. That is, until a recent study of 140 galaxies hosting Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) – another name for active black holes at the center of galaxies – provided strong evidence that many of the galaxies containing these AGN show no signs of past mergers.

The study was performed by an international team of astronomers. Mauricio Cisternas of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy and his team used data from 140 galaxies that were imaged by the XMM-Newton X-ray observatory. The galaxies they sampled had a redshift between z= 0.3 – 1, which means that they are between about 4 and 8 billion light-years away (and thus, the light we see from them is about 4-8 billion years old).

They didn’t just look at the images of the galaxies in question, though; a bias towards classifying those galaxies that show active nuclei to be more distorted from mergers might creep in. Rather, they created a “control group” of galaxies, using images of inactive galaxies from the same redshift as the AGN host galaxies. They took the images from the Cosmic Evolution Survey (COSMOS), a survey of a large region of the sky in multiple wavelengths of light. Since these galaxies were from the same redshift as the ones they wanted to study, they show the same stage in galactic evolution. In all, they had 1264 galaxies in their comparison sample.

The way they designed the study involved a tenet of science that is not normally used in the field of astronomy: the blind study. Cisternas and his team had 9 comparison galaxies – which didn’t contain AGN – of the same redshift for each of their 140 galaxies that showed signs of having an active nucleus.

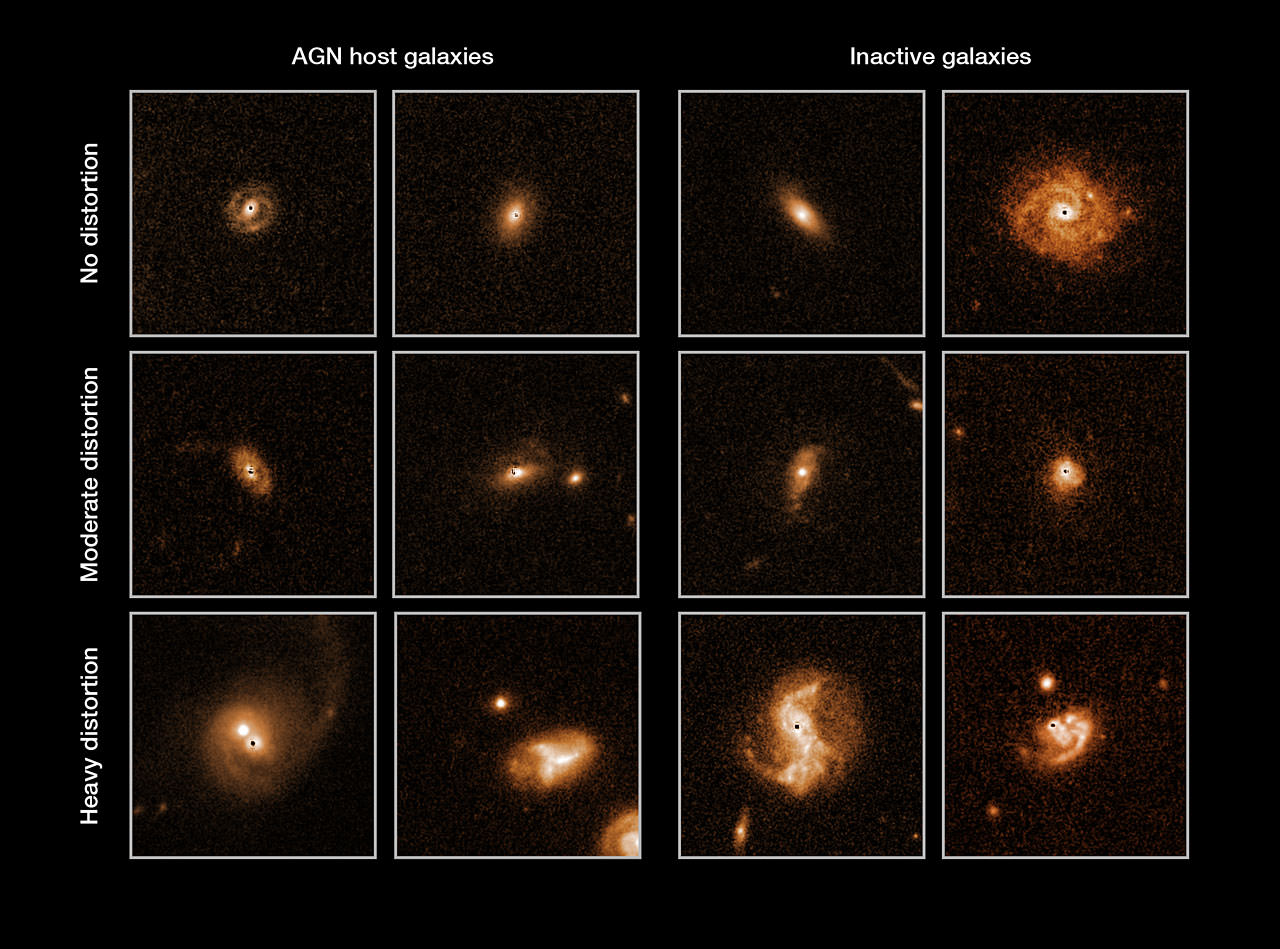

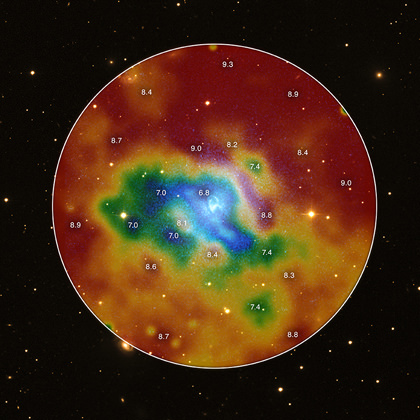

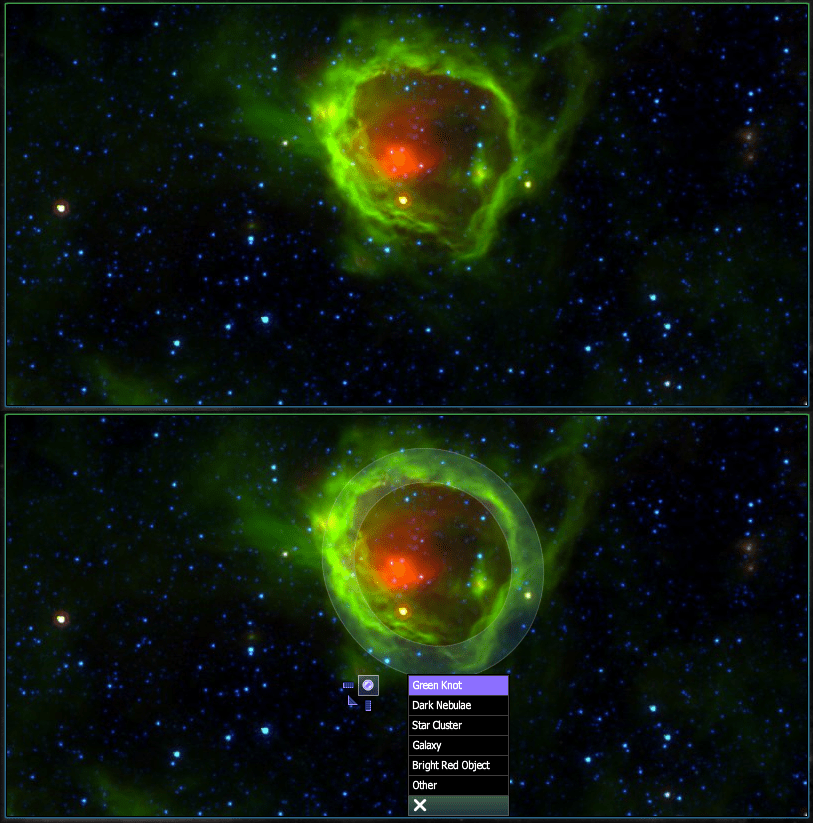

What they did next was remove any sign of the bright active nucleus in the image. This means that the galaxies in their sample of 140 galaxies with AGN would essentially appear to even a trained eye as a galaxy without the telltale signs of an AGN. They then submitted the control galaxies and the altered AGN images to ten different astronomers, and asked them to classify them all as “distorted”, “moderately distorted”, or “not distorted”.

Since their sample size was pretty manageable, and the distortion in many of the galaxies would be too subtle for a computer to recognize, the pattern-seeking human brain was their image analysis tool of choice. This may sound familiar – something similar is being done with enormous success with people who are amateur galaxy classifiers at Galaxy Zoo.

When a galaxy merges with another galaxy, the merger distorts its shape in ways that are identifiable – it will warp a normally smooth elliptical galaxy out of shape, and if the galaxy is a spiral the arms seem to be a bit “unwound”. If it were the case that galactic mergers are the most likely cause of AGN, then those galaxies with an active nucleus would be more probable to show distortion from this past merger.

The team went through this process of blinding the study to eliminate any bias that those looking at the images would have towards classifying AGN as more distorted. By both having a reasonably large sample size of galaxies and removing any bias when analyzing the images, they hoped to definitively show whether the correlation between AGN and mergers exists.

The result? Those galaxies with an Active Galactic Nucleus did not show any more distortion on the whole than those galaxies in the comparison sample. As the authors state in the paper, “Mergers and interactions involving AGN hosts are not dominant, and occur no more frequently than for inactive galaxies.”

This means that astronomers can’t point towards galactic mergers as the main reason for AGN. The study showed that at least 75% of AGN creation – at least between the last 4-8 billion years – must be from sources other than galactic mergers. Likely candidates for these sources include: “galactic harrassment”, those galaxies that don’t collide, but come close enough to gravitationally influence each other; the instability of the central bar in a galaxy; or the collision of giant molecular clouds within the galaxy.

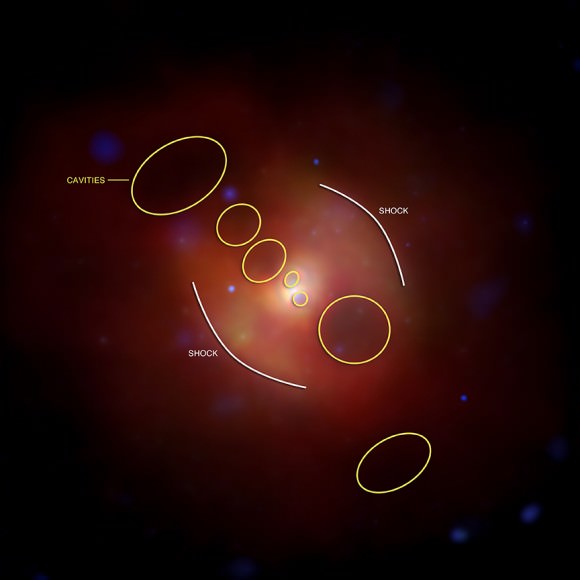

Knowing that AGN aren’t caused in large part by galactic mergers will help astronomers to better understand the formation and evolution of galaxies. The active nuclei in galaxies that host them greatly influence galactic formation. This process is called ‘AGN feedback’, and the mechanisms and effects that result from the interplay between the energy streaming out of the AGN and the surrounding material in the center of a galaxy is still a hot topic of study in astronomy.

Mergers in the more distant past than 8 billion years might yet correlate with AGN – this study only rules out a certain population of these galaxies – and this is a question that the team plans to take on next, pending surveys by the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope. Their study will be published in the January 10 issue of the Astrophysical Journal, and a pre-print version is available on Arxiv.

Source: HST news release, Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Arxiv paper