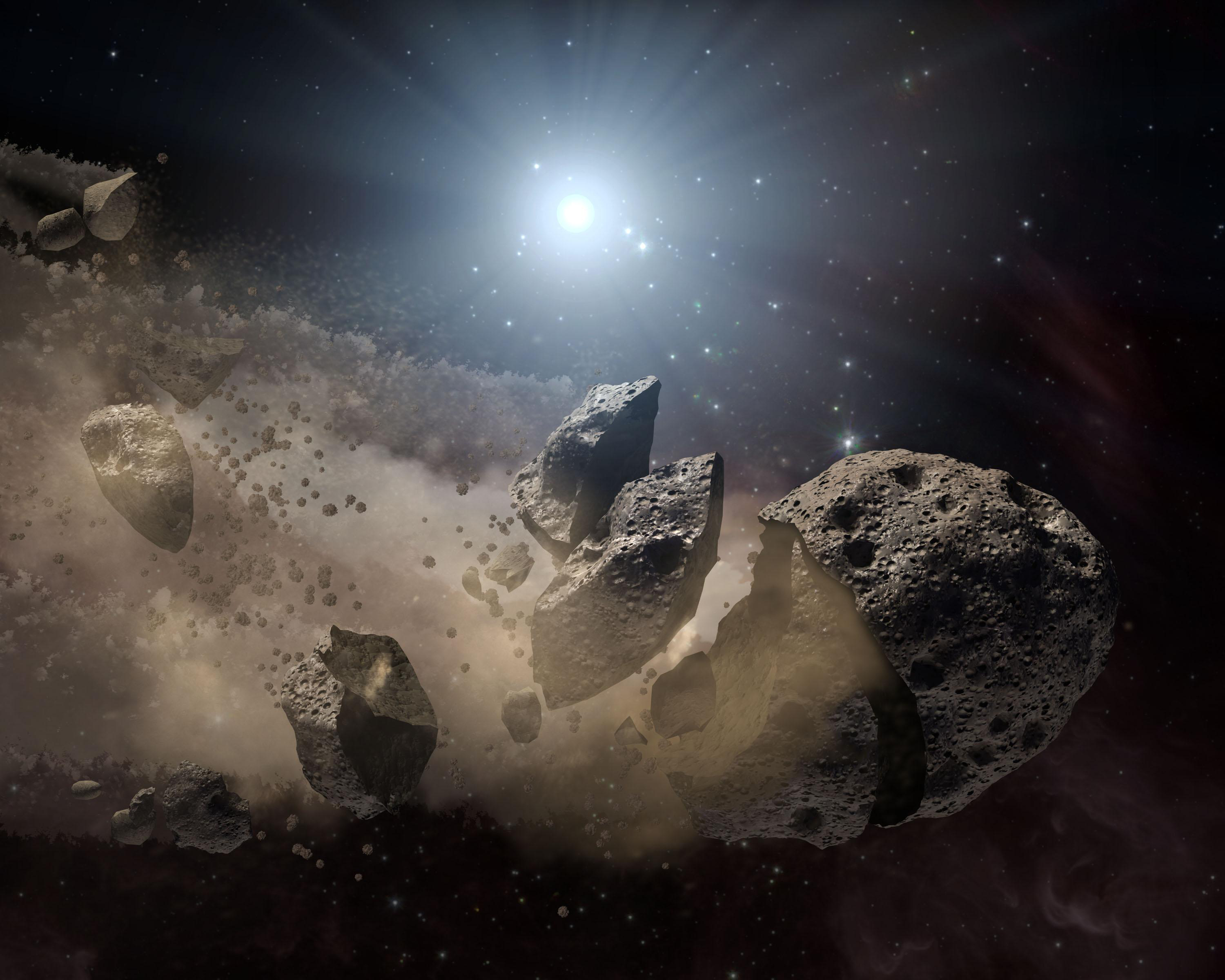

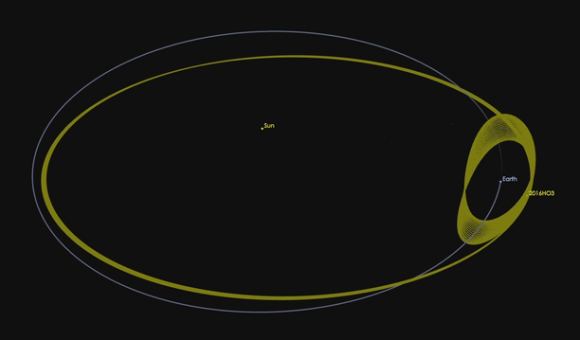

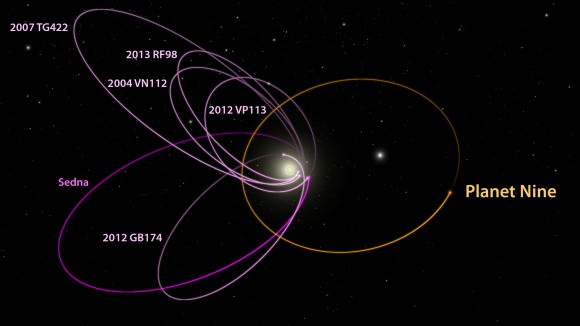

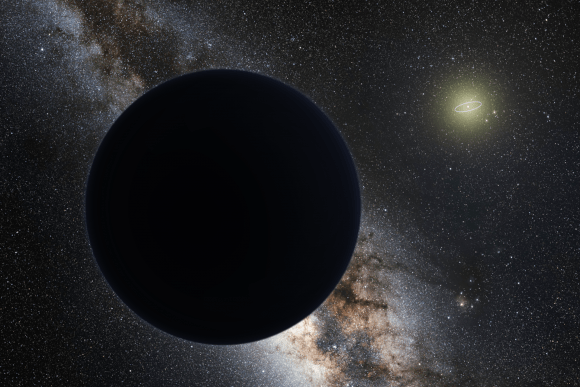

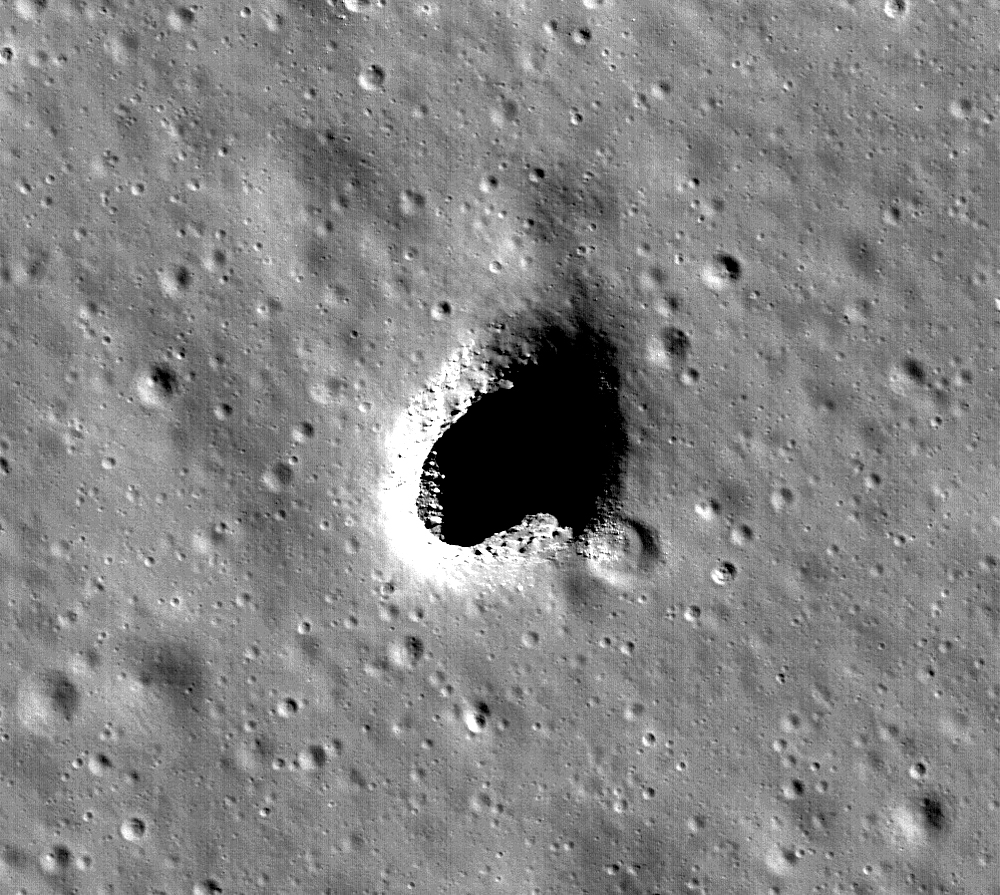

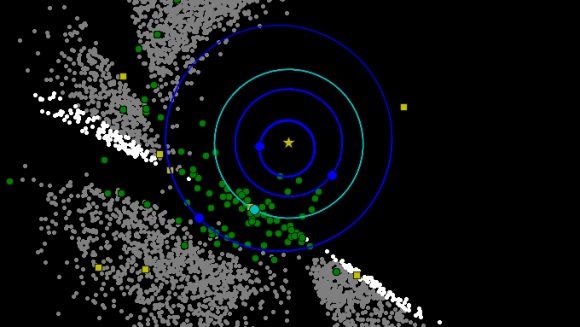

Beyond Earth’s orbit, there are innumerable comets and asteroids that are collectively known as Near-Earth Objects. On occasion, some of these objects will cross Earth’s orbit; and every so often, one will pass too close to Earth and impact on its surface. While most of these objects have been too small to cause serious damage, some have been large enough to trigger Extinction Level Events (ELEs).

For this reason, NASA and other space agencies have spent decades cataloging and monitoring the larger NEAs in order to determine if they might collide with Earth at some point in the future. The only question has been, how many remain to be found? According to a recent analysis performed by Alan W. Harris of MoreData! – a California-based research company – only a handful of NEAs haven’t been catalogued yet.

These findings were the subject of a presentation made this week at the 49th annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences in Provo, Utah. As Harris indicated during the presentation, titled “The Population of Near-Earth Asteroids Revisited”, previous estimates of the remaining NEAs have been plagued by a consequential round-off error that have skewed the results.

The source of this error has to do with how organizations that monitor NEOs determine “size-frequency distribution”. Basically, estimates are given in terms of number versus brightness, since most discovery surveys were conducted in the visible spectrum. This is not a reliable way of determining size though, since asteroids don’t all have the same albedo (aka. reflectivity).

As such, NEA brightness is expressed in units of absolute magnitude (H), where lower numbers indicate brighter objects. The IAU Minor Planet Center – which is responsible for maintaining information on asteroid and other small-body measurements – rounds off the reported values of H to the nearest 0.1 magnitude. As Harris explained during the course of his presentation:

“So, for example, a bin from H of 17.5 to 18.0 is really from 17.55 to 18.05, or 17.45 to 17.95, depending on which side of the bin you take “less than or equal to” rather than ‘less than’.”

While this has not caused much in the way of problems in the past, it has become significant as far as assessments of how many larger objects remain to be found are concerned. Harris first became aware of the potential for problems this past year after Dr. Pasqual Tricario – a Senior Scientist at the Planetary Science Institute – conducted a study that produced estimates different from those obtained by Harris and Italian astronomer Germano D’Abramo two years before.

The 2015 study conducted by Harris and D’Abramo – which appeared in Icarus under the title “The population of near-Earth asteroids” – yielded an estimate of 990 NEAs that were larger than 1 km in diameter. However, Tricario’s study (“The near-Earth asteroid population from two decades of observations“, also published in Icarus), which was based on the opposite “less than or equal to” assumption, produced estimates that were 10% lower.

As Harris explained, this prompted D’Adramo and him to considered a different approach. “We corrected the problem for the current analysis by choosing bin boundaries at .05 magnitudes, e.g. 17.25 to 17.75, so the 0.1 round-off thresholds naturally put objects in the right bin,” he said. “When Tricarico and I each made these corrections, our population estimates fell into almost perfect agreement.”

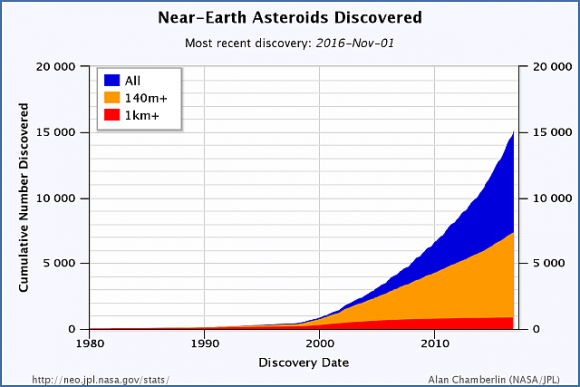

After applying the correction, Harris and D’Abramo’s overall estimate of undiscovered NEAs dropped from 990 to 921 ± 20. Beyond allowing for consistency between different studies, these corrected estimates also reduced the total number of undiscovered objects that remain undiscovered. According to the latest tallies from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 884 NEAs that are about 1 km in diameter have been discovered so far.

Based on the previous population estimate of 990 objects, this implied that the current surveys are 89% complete and 106 were yet to be found. When the corrections were applied to these numbers, JPL’s surveys now appears to be 96% complete, and only 37 objects remain to be found (almost three times less). Naturally, these new estimates depends on their own sets of assumptions, and different results can be obtained based on different criteria.

Still, a reduced estimate of undiscovered asteroids is definitely encouraging news. Especially when one considers how hazardous large asteroids are to the safety and well-being of life here on Earth. As of October 3rd, 2017, NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) announced that there are a total of 157 potentially hazardous asteroids out there. Knowing that only a few more need to be found is bound to help some of us sleep at night!

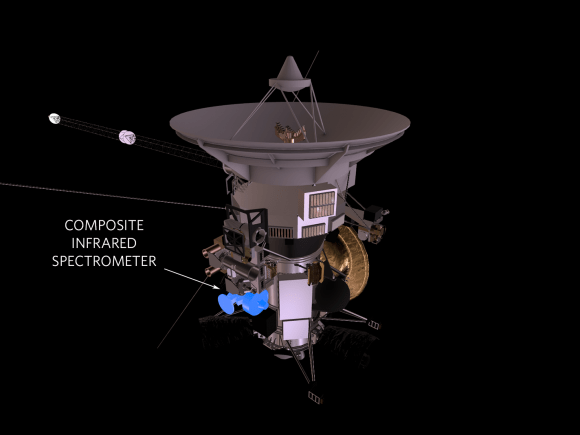

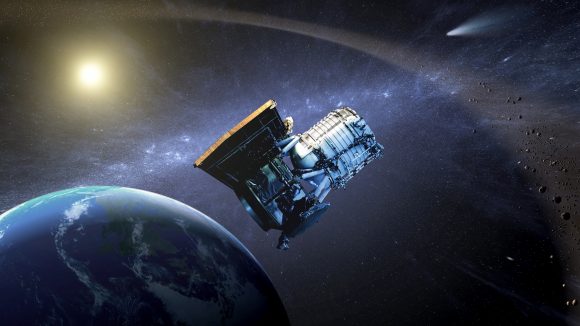

Future studies are also expected to benefit from the deployment of next-generation missions. Thanks to the efforts of NASA’s Near-Earth-Object WISE (NEOWISE) mission, which looks for NEOs in the infrared band (rather than visible light), that number of known NEOs has increased substantially. With the deployment of the James Webb Space Telescope, those numbers are expected to reach even higher.

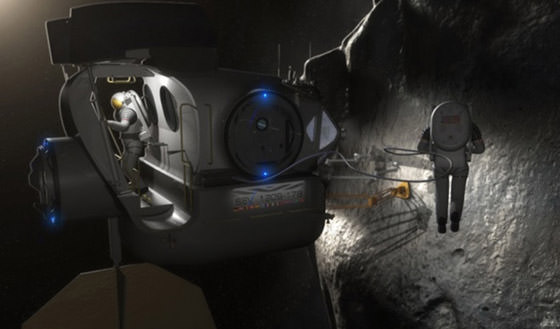

Between improvements in technology and methodology, a day may yet come when all Near-Earth Objects – be they big or small, potentially hazardous or harmless – are accounted for. Combined with asteroid defenses, like directed-energy beams or robots spacecraft capable of attaching themselves to asteroids and redirecting them, Extinction Level Events might very well become a thing of the past.

Further Reading: The Spaceguard Center