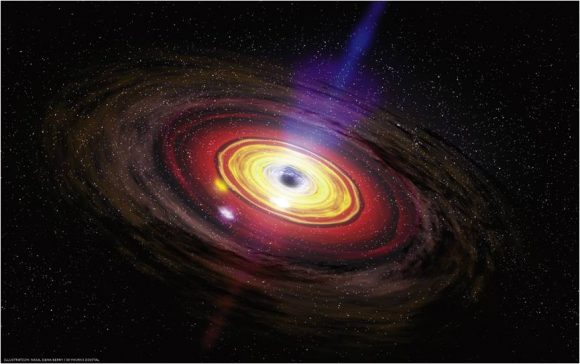

Ever since the discovery of Sagittarius A* at the center of our galaxy, astronomers have come to understand that most massive galaxies have a Supermassive Black Hole (SMBH) at their core. These are evidenced by the powerful electromagnetic emissions produced at the nuclei of these galaxies – which are known as “Active Galatic Nuclei” (AGN) – that are believed to be caused by gas and dust accreting onto the SMBH.

For decades, astronomers have been studying the light coming from AGNs to determine how large and massive their black holes are. This has been difficult, since this light is subject to the Doppler effect, which causes its spectral lines to broaden. But thanks to a new model developed by researchers from China and the US, astronomers may be able to study these Broad Line Regions (BLRs) and make more accurate estimates about the mass of black holes.

The study, “Tidally disrupted dusty clumps as the origin of broad emission lines in active galactic nuclei“, recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature. The study was led by Jian-Min Wang, a researcher from the Institute of High Energy Physics (IHEP) at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, with assistance from the University of Wyoming and the University of Nanjing.

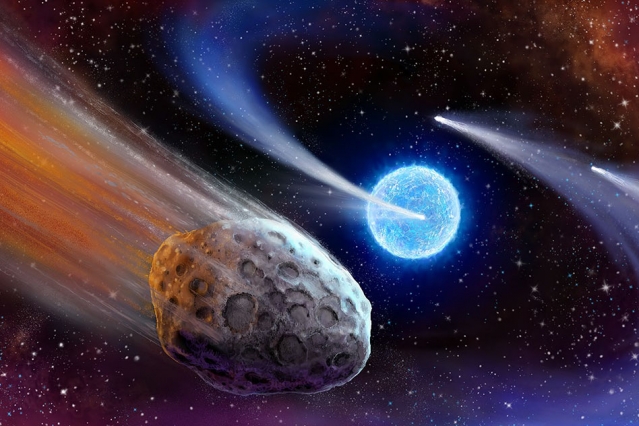

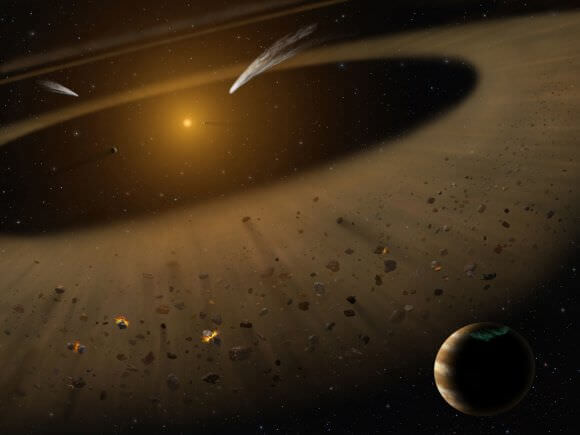

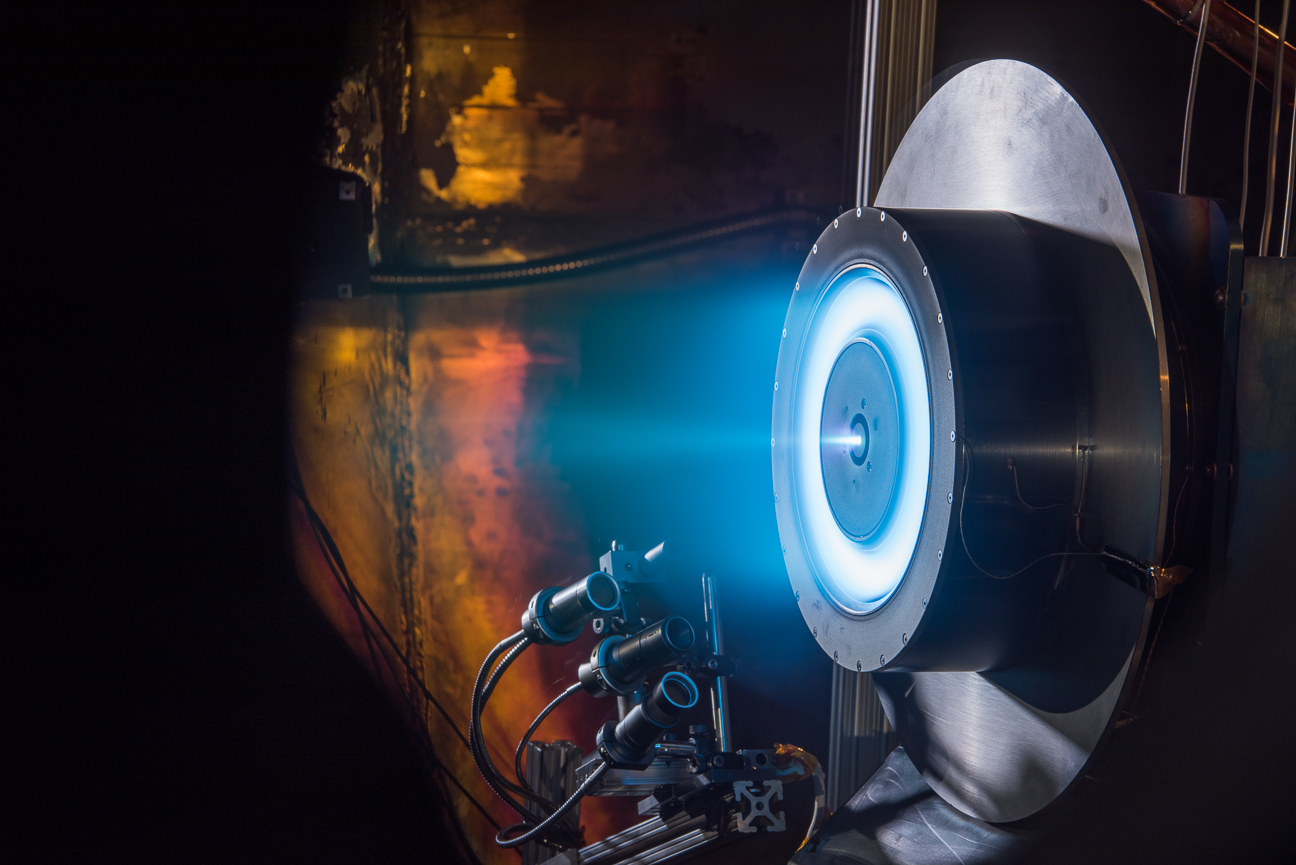

To break it down, SMBHs are known for having a torus of gas and dust that surrounds them. The black hole’s gravity accelerates gas in this torus to velocities of thousands of kilometers per second, which causes it to heat up and emit radiation at different wavelengths. This energy eventually outshined the entire surrounding galaxy, which is what allows astronomers to determine the presence of an SMBH.

As Michael Brotherton, a UW professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy and a co0author on the study, explained in a UW press release:

“People think, ‘It’s a black hole. Why is it so bright?’ A black hole is still dark. The discs reach such high temperatures that they put out radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum, which includes gamma rays, X-rays, UV, infrared and radio waves. The black hole and surrounding accreting gas the black hole is feeding on is fuel that turns on the quasar.”

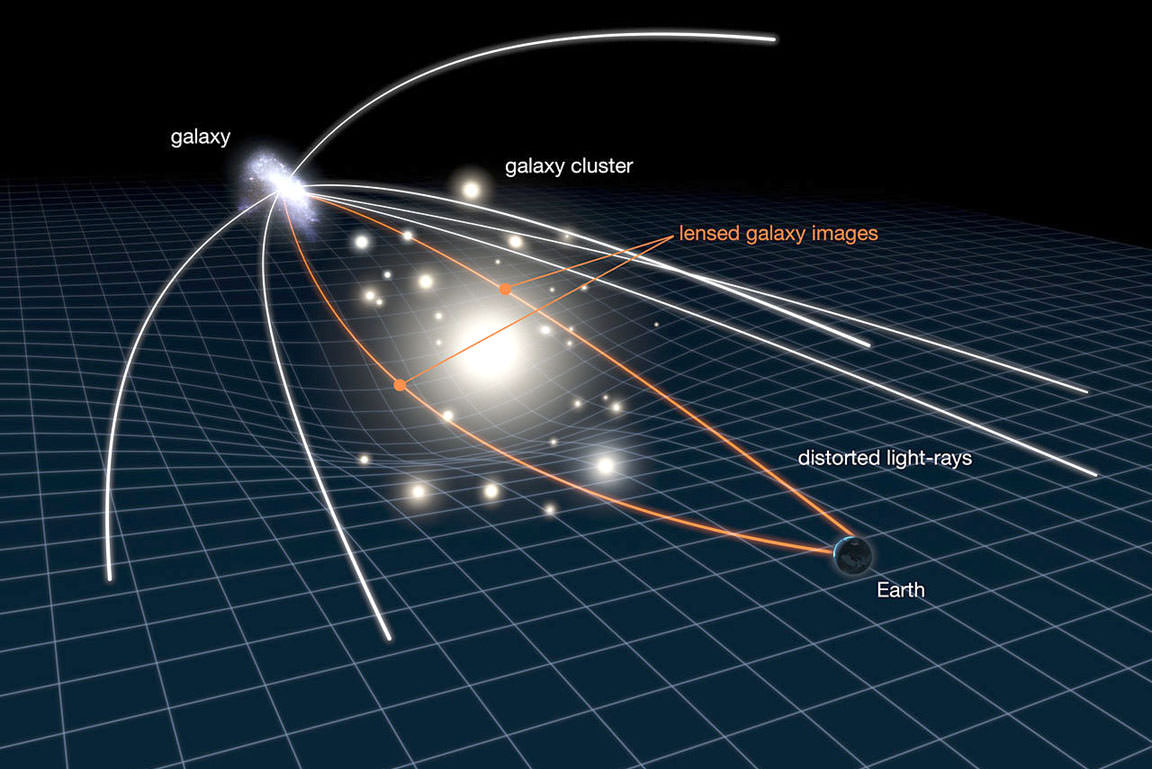

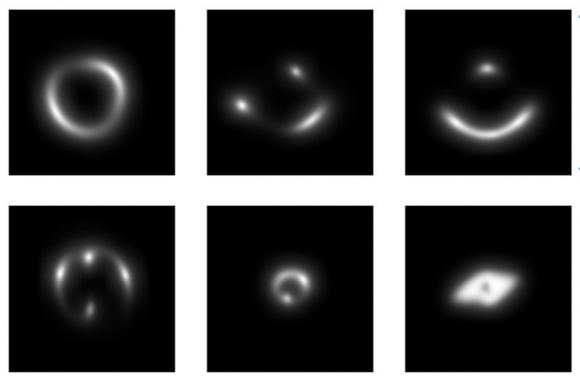

The problem with observing these bright regions comes from the fact that the gases within them are moving so quickly in different directions. Whereas gas moving away (relative to us) is shifted towards the red end of the spectrum, gas that is moving towards us is shifted towards the blue end. This is what leads to a Broad Line Region, where the spectrum of the emitted light becomes more like a spiral, making accurate readings difficult to obtain.

Currently, the measurement of the mass of SMBHs in active galactic nuclei relies the “reverberation mapping technique”. In short, this involves using computer models to examine the symmetrical spectral lines of a BLR and measuring the time delays between them. These lines are believed to arise from gas that has been photoionized by the gravitational force of the SMBH.

However, since there is little understanding of broad emission lines and the different components of BLRs, this method gives rise to some uncertainties off between 200 and 300%. “We are trying to get at more detailed questions about spectral broad-line regions that help us diagnose the black hole mass,” said Brotherton. “People don’t know where these broad emission line regions come from or the nature of this gas.”

In contrast, the team led by Dr. Wang adopted a new type of computer model that considered the dynamics of the gas torus surrounding a SMBH. This torus, they assume, would be made up of discrete clumps of matter that would be tidally disrupted by the black hole, resulting in some gas flowing into it (aka. accreting on it) and some being ejected as outflow.

From this, they found that the emission lines in a BLR are subject to three characteristics – “asymmetry”, “shape” and “shift”. After examining various emissions lines – both symmetrical and asymmetrical – they found that these three characteristics were strongly dependent on how bright the gas clumps were, which they interpreted as being a result of the angle of their motion within the torus. Or as Dr. Brotherton put it:

“What we propose happens is these dusty clumps are moving. Some bang into each other and merge, and change velocity. Maybe they move into the quasar, where the black hole lives. Some of the clumps spin in from the broad-line region. Some get kicked out.”

Credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF

In the end, their new model suggests that tidally disrupted clumps of matter from a black hole torus may represent the source of the BLR gas. Compared to previous models, the one devised by Dr. Wang and his colleagues establishes a connection between different key processes and components in the vicinity of a SMBH. These include the feeding of the black hole, the source of photoionized gas, and the dusty torus itself.

While this research does not resolve all the mysteries surrounding AGNs, it is an important step towards obtaining accurate mass estimates of SMBHs based on their spectral lines. From these, astronomers could be able to more accurately determine what role these black holes played in the evolution of large galaxies.

The study was made possible thanks with support provided by the National Key Program for Science and Technology Research and Development, and the Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, both of which are administered by the Chinese Academy of Sciences.