As a species, we humans tend to take it for granted that we are the only ones that live in sedentary communities, use tools, and alter our landscape to meet our needs. It is also a foregone conclusion that in the history of planet Earth, humans are the only species to develop machinery, automation, electricity, and mass communications – the hallmarks of industrial civilization.

But what if another industrial civilization existed on Earth millions of years ago? Would we be able to find evidence of it within the geological record today? By examining the impact human industrial civilization has had on Earth, a pair of researchers conducted a study that considers how such a civilization could be found and how this could have implications in the search for extra-terrestrial life.

The study, which recently appeared online under the title “The Silurian Hypothesis: Would it be possible to detect an industrial civilization in the geological record“, was conducted by Gavin A. Schmidt and Adam Frank – a climatologist with the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (NASA GISS) and an astronomer from the University of Rochester, respectively.

As they indicate in their study, the search for life on other planets has often involved looking to Earth-analogues to see what kind conditions life could exist under. However, this pursuit also entails the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence (SETI) that would be capable of communicating with us. Naturally, it is assumed that any such civilization would need to develop and industrial base first.

This, in turn, raises the question of how often an industrial civilization might develop – what Schmidt and Frank refer to as the “Silurian Hypothesis”. Naturally, this raises some complications since humanity is the only example of an industrialized species that we know of. In addition, humanity has only been an industrial civilization for the past few centuries – a mere fraction of its existence as a species and a tiny fraction of the time that complex life has existed on Earth.

For the sake of their study, the team first noted the importance of this question to the Drake Equation. To recap, this theory states that the number of civilizations (N) in our galaxy that we might be able to communicate is equal to the average rate of star formation (R*), the fraction of those stars that have planets (fp), the number of planets that can support life (ne), the number of planets that will develop life ( fl), the number of planets that will develop intelligent life (fi), the number civilizations that would develop transmission technologies (fc), and the length of time these civilizations will have to transmit signals into space (L).

This can be expressed mathematically as: N = R* x fp x ne x fl x fi x fc x L

As they indicate in their study, the parameters of this equation may change thanks to the addition of the Silurian Hypothesis, as well as recent exoplanets surveys:

“If over the course of a planet’s existence, multiple industrial civilizations can arise over the span of time that life exists at all, the value of fc may in fact be greater than one. This is a particularly cogent issue in light of recent developments in astrobiology in which the first three terms, which all involve purely astronomical observations, have now been fully determined. It is now apparent that most stars harbor families of planets. Indeed, many of those planets will be in the star’s habitable zones.”

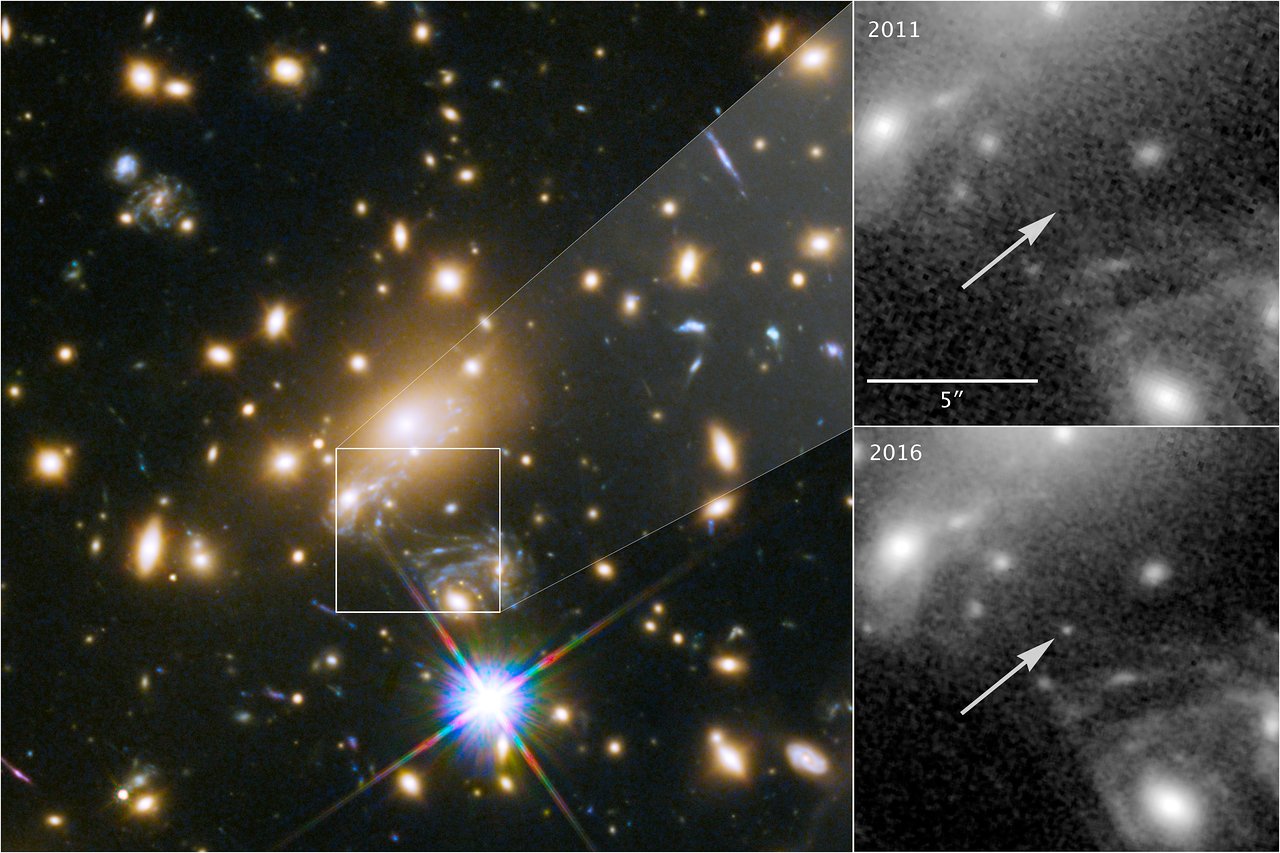

In short, thanks to improvements in instrumentation and methodology, scientists have been able to determine the rate at which stars form in our galaxy. Furthermore, recent surveys for extra-solar planets have led some astronomers to estimate that our galaxy could contains as many as 100 billion potentially-habitable planets. If evidence could be found of another civilization in Earth’s history, it would further constrain the Drake Equation.

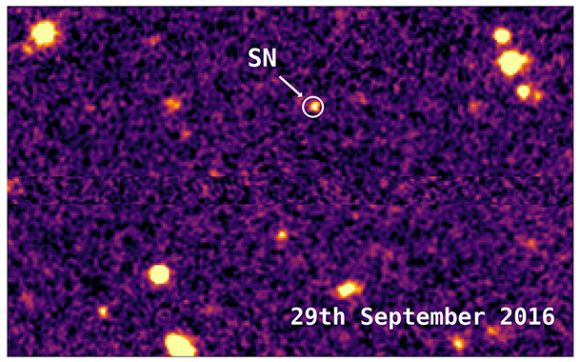

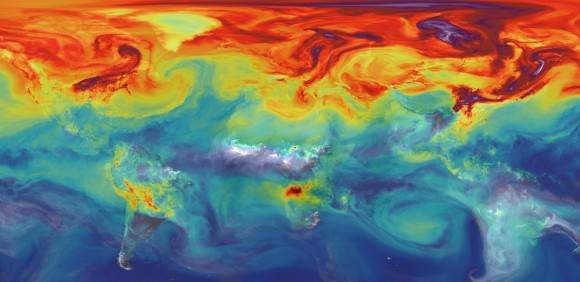

They then address the likely geologic consequences of human industrial civilization and then compare that fingerprint to potentially similar events in the geologic record. These include the release of isotope anomalies of carbon, oxygen, hydrogen and nitrogen, which are a result of greenhouse gas emissions and nitrogen fertilizers. As they indicate in their study:

“Since the mid-18th Century, humans have released over 0.5 trillion tons of fossil carbon via the burning of coal, oil and natural gas, at a rate orders of magnitude faster than natural long-term sources or sinks. In addition, there has been widespread deforestation and addition of carbon dioxide into the air via biomass burning.”

They also consider increased rates of sediment flow in rivers and its deposition in coastal environments, as a result of agricultural processes, deforestation, and the digging of canals. The spread of domesticated animals, rodents and other small animals are also considered – as are the extinction of certain species of animals – as a direct result of industrialization and the growth of cities.

The presence of synthetic materials, plastics, and radioactive elements (caused by nuclear power or nuclear testing) will also leave a mark on the geological record – in the case of radioactive isotopes, sometimes for millions of years. Finally, they compare past extinction level events to determine how they would compare to a hypothetical event where human civilization collapsed. As they state:

“The clearest class of event with such similarities are the hyperthermals, most notably the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (56 Ma), but this also includes smaller hyperthermal events, ocean anoxic events in the Cretaceous and Jurassic, and significant (if less well characterized) events of the Paleozoic.”

These events were specifically considered because they coincided with rises in temperatures, increases in carbon and oxygen isotopes, increased sediment, and depletions of oceanic oxygen. Events that had a very clear and distinct cause, such as the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event (caused by an asteroid impact and massive volcanism) or the Eocene-Oligocene boundary (the onset of Antarctic glaciation) were not considered.

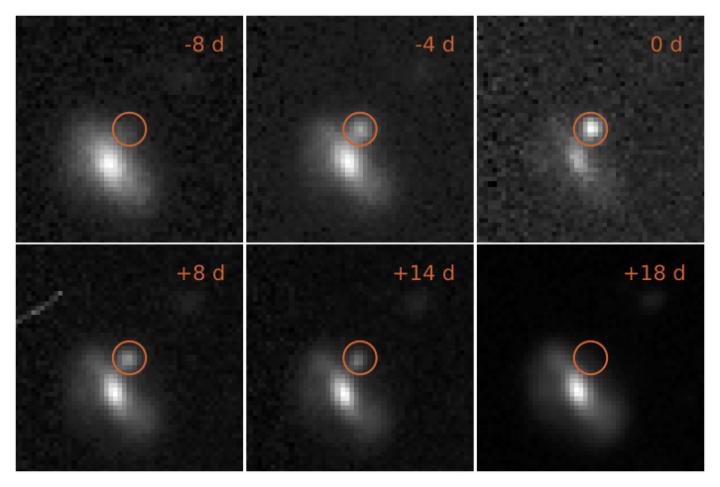

According to the team, the events they did consider (known as “hyperthermals”) show similarities to the Anthropocene fingerprint that they identified. In particular, according to research cited by the authors, the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) shows signs that could be consistent with anthorpogenic climate change. These include:

“[A] fascinating sequence of events lasting 100–200 kyr and involving a rapid input (in perhaps less than 5 kyr) of exogenous carbon into the system, possibly related to the intrusion of the North American Igneous Province into organic sediments. Temperatures rose 5–7?C (derived from multiple proxies), and there was a negative spike in carbon isotopes (>3%), and decreased ocean carbonate preservation in the upper ocean.”

Finally, the team addressed some possible research directions that might improve the constraints on this question. This, they claim, could consist of a “deeper exploration of elemental and compositional anomalies in extant sediments spanning previous events be performed”. In other words, the geological record for these extinction events should be examined more closely for anomalies that could be associated with industrial civilization.

If any anomalies are found, they further recommend that the fossil record could be examined for candidate species, which would raise questions about their ultimate fate. Of course, they also acknowledge that more evidence is necessary before the Silurian Hypothesis can be considered viable. For instance, many past events where abrupt Climate Change took place have been linked to changes in volcanic/tectonic activity.

Second, there is the fact that current changes in our climate are happening faster than in any other geological period. However, this is difficult to say for certain since there are limits when it comes to the chronology of the geological record. In the end, more research will be necessary to determine how long previous extinction events (those that were not due to impacts) took as well.

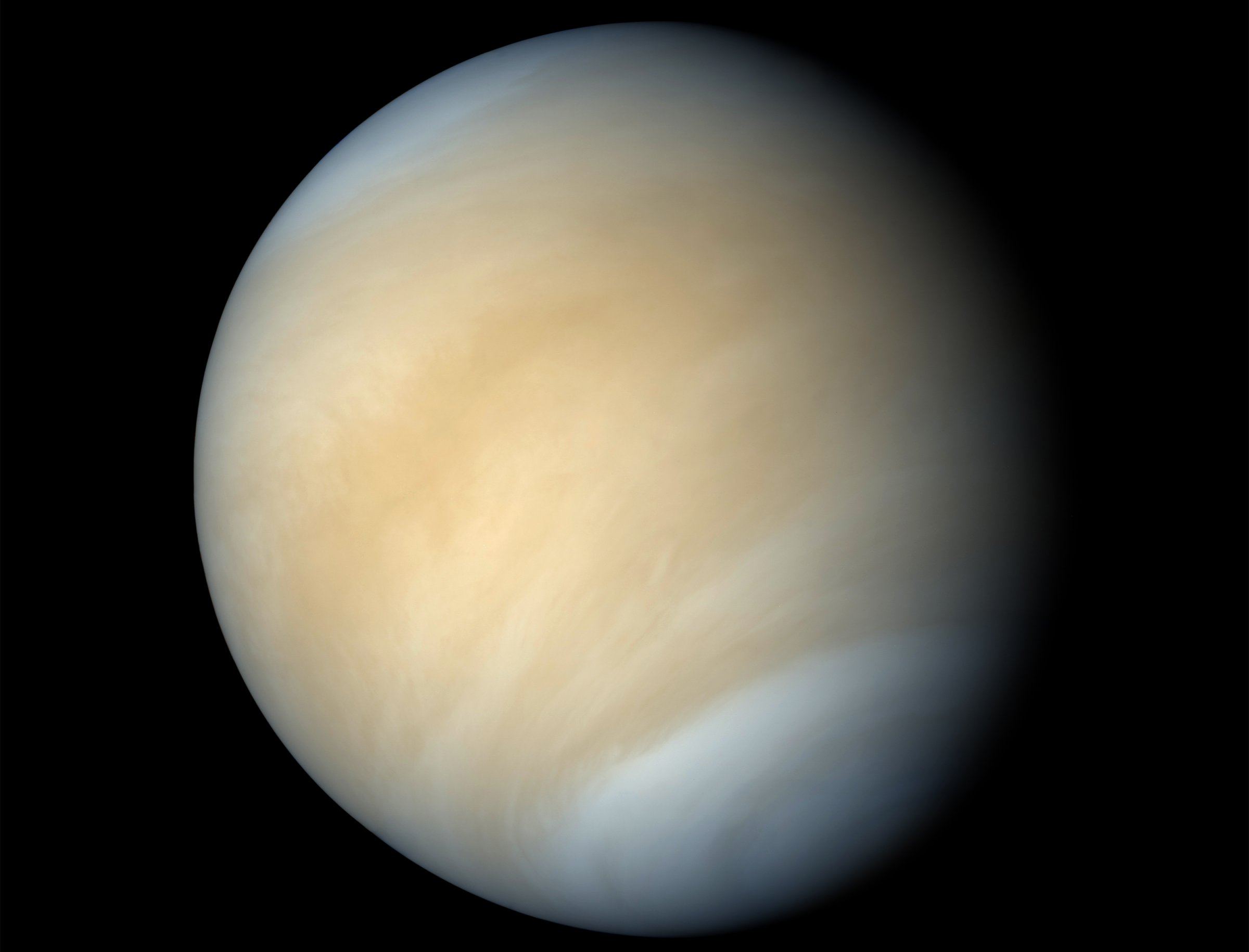

Beyond Earth, this study may also have implications for the study of past life on planets like Mars and Venus. Here too, the authors suggest how explorations of both could reveal the existence of past civilizations, and maybe even bolster the possibility of finding evidence of past civilizations on Earth.

Further Reading: arXiv