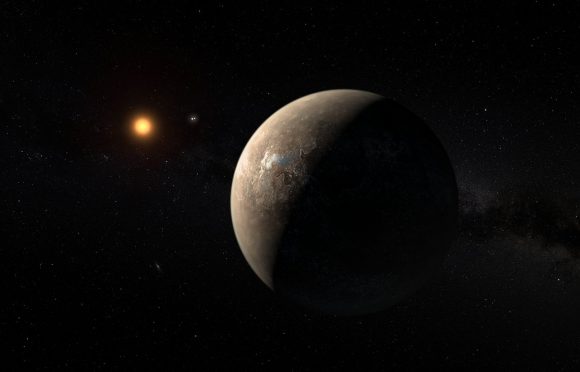

Since its discovery was announced in August of 2016, Proxima b has been an endless source of wonder and the target of many scientific studies. In addition to being the closest extra-solar planet to our Solar System, this terrestrial planet also orbits within Proxima Centauri’s circumstellar habitable zone (aka. “Goldilocks Zone”). As a result, scientists have naturally sought to determine if this planet could actually be home to extra-terrestial life.

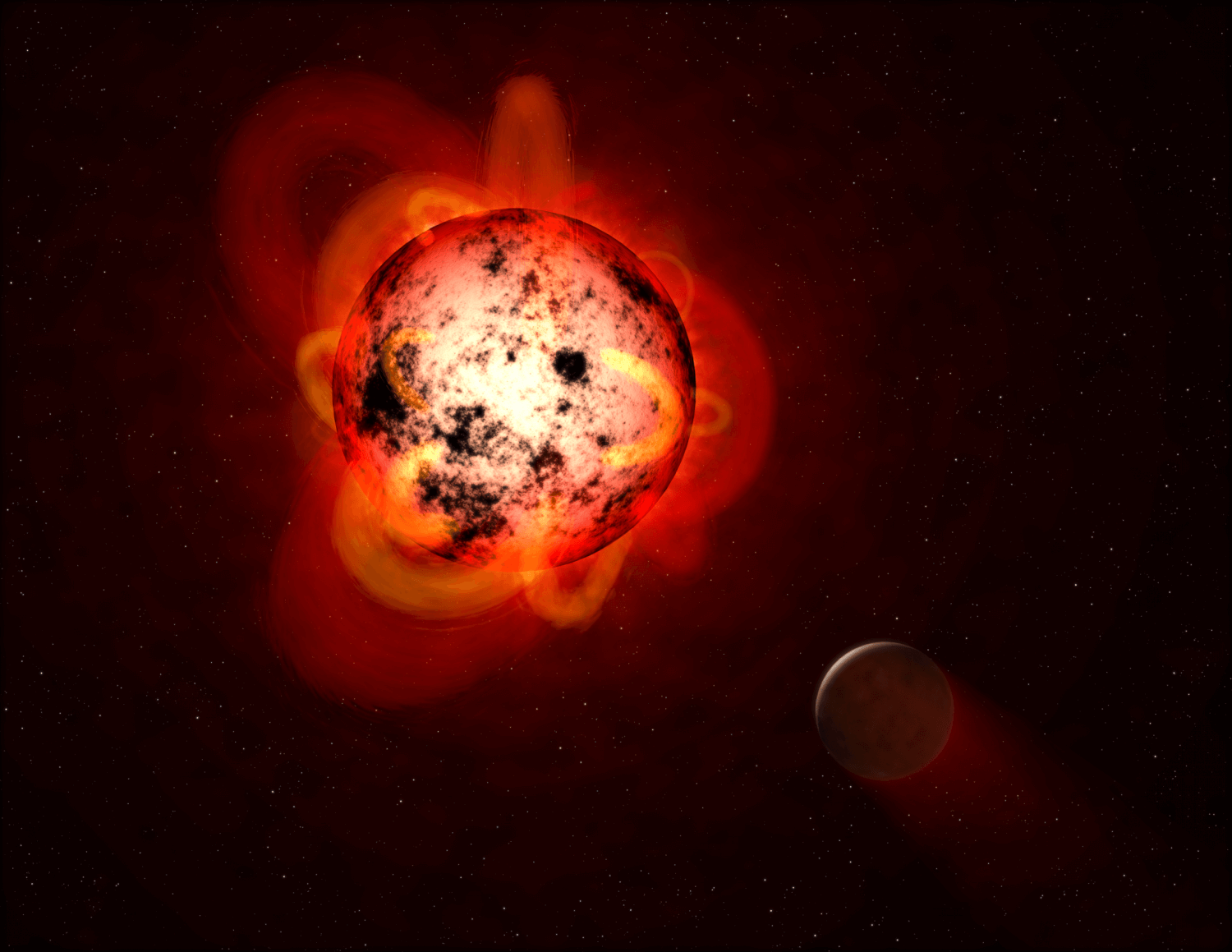

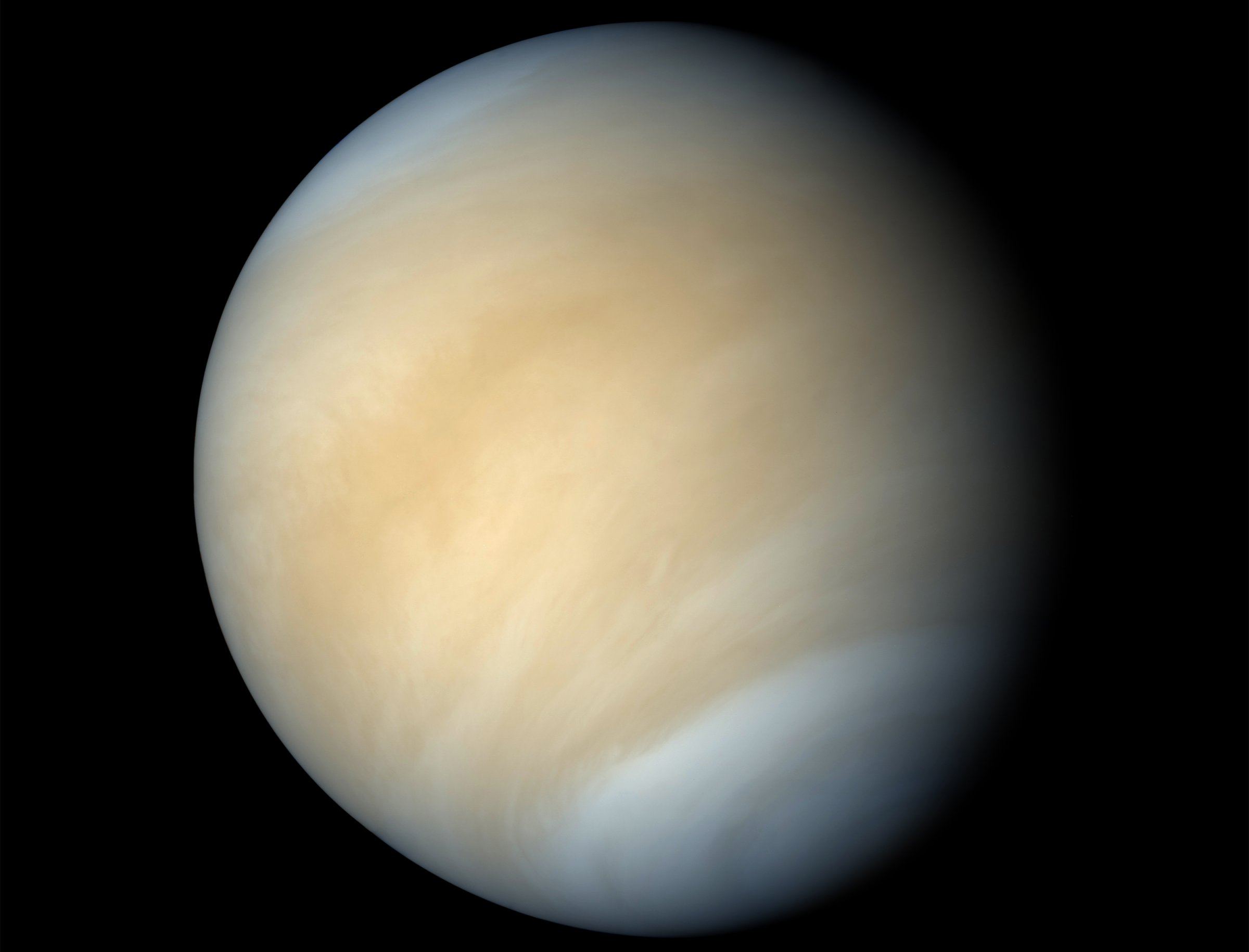

Many of these studies have been focused on whether or not Proxima b could retain an atmosphere and liquid water on its surface in light of the fact that it orbits an M-type (red dwarf) star. Unfortunately, many of these studies have revealed that this is not likely due to flare activity. According to a new study by an international team of scientists, Proxima Centauri released a superflare that was so powerful, it would have been lethal to any life as we know it.

The study, titled “The First Naked-Eye Superflare Detected from Proxima Centauri“, recently appeared online. The team was led by Howard Ward, a PhD candidate in physics and astronomy at the UNC Chapel Hill, with additional members from the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, the University of Washington, the University of Colorado, the University of Barcelona and the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University.

As they indicate in their study, solar flare activity would be one of the greatest potential threats to planetary habitability in a system like Proxima Centauri. As they explain:

“[W]hile ozone in an Earth-like planet’s atmosphere can shield the planet from the intense UV flux associated with a single superflare, the atmospheric ozone recovery time after a superflare is on the order of years. A sufficiently high flare rate can therefore permanently prevent the formation of a protective ozone layer, leading to UV radiation levels on the surface which are beyond what some of the hardiest-known organisms can survive.”

In addition stellar flares, quiescent X-ray emissions and UV flux from a red dwarf star can would be capable of stripping planetary atmospheres over the course of several billion years. And while multiple studies have been conducted that have explored low- and moderate-energy flare events on Proxima, only one high-energy event has even been observed.

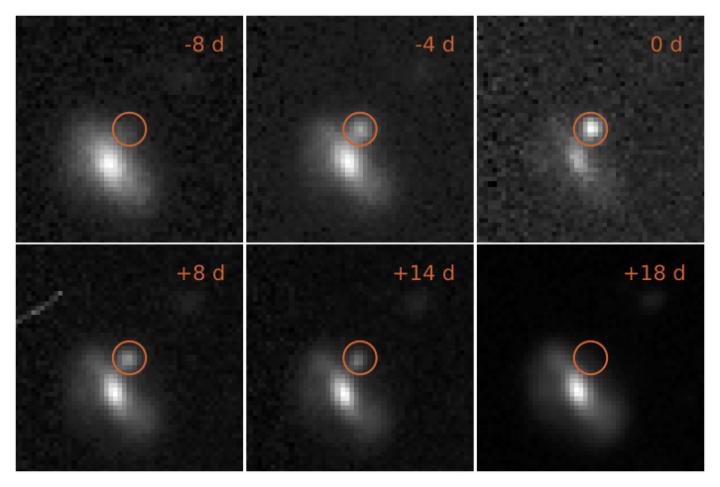

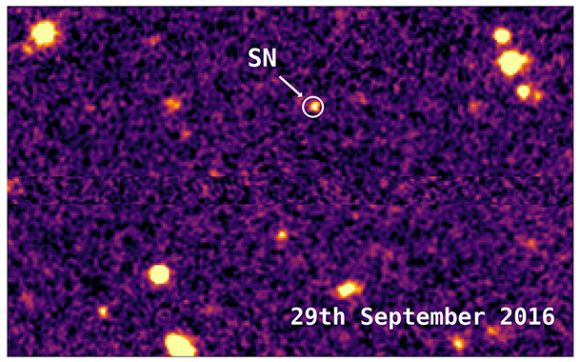

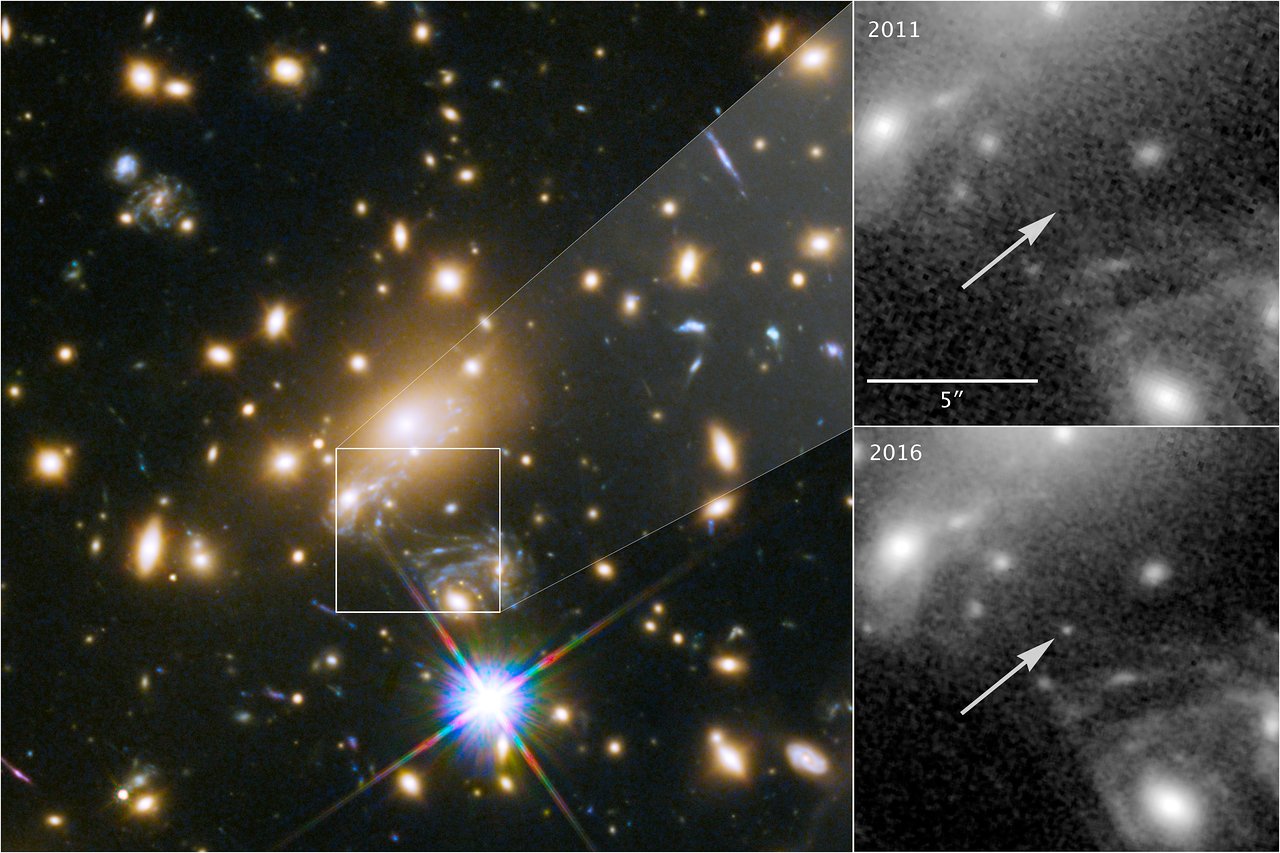

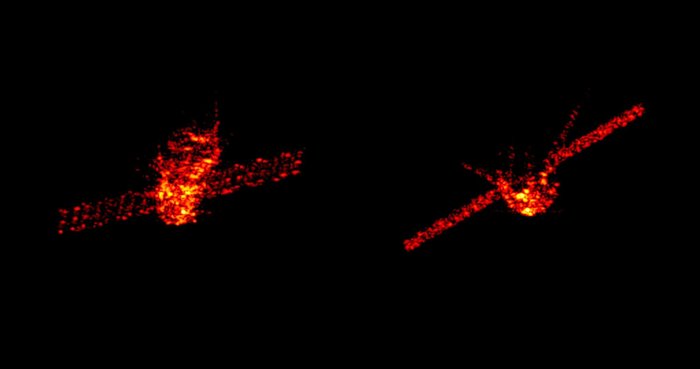

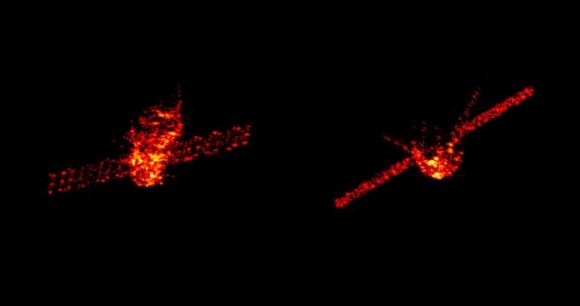

This occurred on March of 2016, when Proxima Centauri emitted a superflare that was so bright, it was visible to the naked eye. This flare was observed by the Evryscope, an array of telescopes – funded through the National Science Foundation‘s Advanced Technologies and Instrumentation (ATI) and Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) programs – that is pointed at every part of the accessible sky simultaneously and continuously.

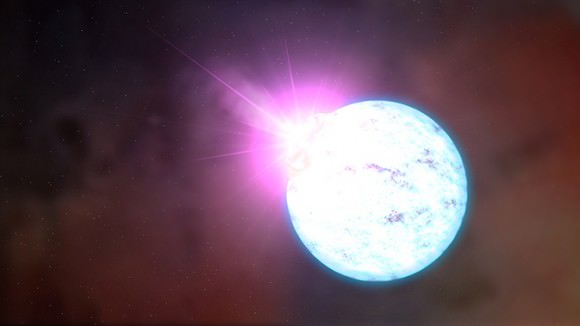

As the team indicates in their study, the March 2016 superflare was the first to be observered from Proxima Centauri, and was rather powerful:

“In March 2016 the Evryscope detected the first-known Proxima superflare. The superflare had a bolometric energy of 10^33.5 erg, ~10× larger than any previously-detected flare from Proxima, and 30×larger than any optically measured Proxima flare. The event briefly increased Proxima’s visible-light emission by a factor of 38× averaged over the Evryscope’s 2-minute cadence, or ~68× at the cadence of the human eye. Although no M-dwarfs are usually visible to the naked-eye, Proxima briefly became a magnitude-6.8 star during this superflare, visible to dark-site naked-eye observers.”

The superflare coincided with the three-month Pale Red Dot campaign, which was responsible for first revealing the existence of Proxima b. While monitoring the star with the HARPS spectrograph – which is part of the 3.6 m telescope at the ESO’s La Silla Observatory in Chile – the campaign team also obtaining spectra on March 18th, 08:59 UT (just 27 minutes after the flare peaked at 08:32 UT).

The team also noted that over the last two years, the Evryscope has recorded 23 other large Proxima flares, ranging in energy from 10^30.6 erg to 10^32.4 erg. Coupled with rates of a single superflare detection, they predict that at least five superflares occur each year. They then combined this data with the high-resolution HARPS spectroscopy to constrain the superflare’s UV spectrum and any associated coronal mass ejections.

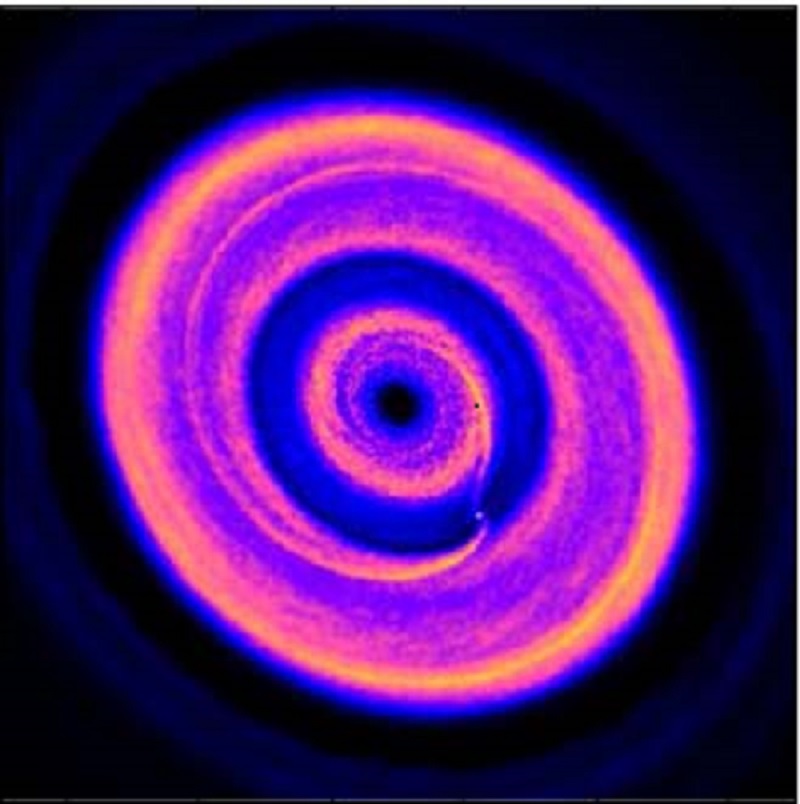

The team then used the HARPS spectra and the Evryscope flare rates to create a model to determine what effects this star would have on a nitrogen-oxygen atmosphere. This included how long the planet’s protective ozone layer would be able to withstand the blasts, and what effect regular exposure to radiation would have on terrestrial organisms.

“[T]he repeated flaring is sufficient to reduce the ozone of an Earth-like atmosphere by 90% within five years. We estimate complete depletion occurs within several hundred kyr. The UV light produced by the Evryscope superflare therefore reached the surface with ~100× the intensity required to kill simple UV-hardy microorganisms, suggesting that life would struggle to survive in the areas of Proxima b exposed to these flares.”

Essentially, this and other studies have concluded that any planets orbiting Proxima Centauri would not be habitable for very long, and likely became lifeless balls of rock a long time ago. But beyond our closest neighboring star system, this study also has implications for other M-type star systems. As they explain, red dwarf stars are the most common in our galaxy – roughly 75% of the population – and two-thirds of these stars experience active flare activity.

As such, measuring the impact that superflares have on these worlds will be a necessary component to determining whether or not exoplanets found by future missions are habitable. Looking ahead, the team hopes to use the Evryscope to examine other star systems, particularly those that are targets for the upcoming Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) mission.

“Beyond Proxima, Evryscope has already performed similar long-term high-cadence monitoring of every other Southern TESS planet-search target, and will therefore be able to measure the habitability impact of stellar activity for all Southern planetsearch-target M-dwarfs,” they write. “In conjunction with coronal-mass-ejection searches from long- wavelength radio arrays like the [Long Wavelength Array], the Evryscope will constrain the long-term atmospheric effects of this extreme stellar activity.”

For those who hoped that humanity might find evidence of extra-terrestrial life in their lifetimes, this latest study is certainly a letdown. It’s also disappointing considering that in addition to being the most common type of star in the Universe, some research indicates that red dwarf stars may be the most likely place to find terrestrial planets. However, even if two-thirds of these stars are active, that still leaves us with billions of possibilities.

It is also important to note that these studies help ensure that we can determine which exoplanets are potentially habitable with greater accuracy. In the end, that will be the most important factor when it comes time to decide which of these systems we might try to explore directly. And if this news has got you down, just remember the worlds of the immortal Carl Sagan:

“The universe is a pretty big place. If it’s just us, seems like an awful waste of space.”

Further Reading: arXiv