[/caption]

Some potentially good news for exoplanet fans, and Kepler fans in particular – Kepler scientists are asking for a mission extension and seem reasonably confident they will get it. Otherwise, funding is due to run out in November of 2012. It is crucial that Kepler receive renewed funding in order to continue its already incredibly successful search for planets orbiting other stars. Its primary goal — and the holy grail of exoplanet research — is finding worlds that are about the size of Earth, orbiting in the “habitable zone” of stars that are similar to our Sun, where temperatures could allow liquid water on their surfaces.

But finding those ideal smaller planets requires several years of observations, in order for Kepler to confirm a repeated orbit as a planet transits its star. The larger the orbit, the longer the observation time needed to view multilple transits. Most of the planetary candidates found already orbit much closer to their stars, hence taking less time to complete an orbit, and can more easily be detected within the first few years of the mission.

Kepler has already obtained very compelling data on a wide variety of planets since it was launched in 2009, with 1,235 candidates found so far (about 25 of which have been confirmed to date), but further refining of the data will take more time; a few more years would do just fine. The exciting trend has been that smaller, rocky planets appear to be much more common than gas giants; good news for those hoping to finds worlds similar to Earth that could be habitable (or, of course, inhabited!).

It is estimated it would cost about $20 million per year to keep Kepler functioning past 2012, which doesn’t sound too bad considering that about $600 million has already been invested in the mission. NASA’s budget, like everyone else’s, is tight though these days, so it isn’t a done deal yet.

The proposal will be submitted in January, with an answer expected by next April or May.

Of those 1,235 candidates found so far, have any been ruled out?

Is there any way that they could be ruled out? (without going there or waiting for better telescopes, that is)

Repeated observations for periodic transits is a sign of an orbiting planet. The transit passing of a planet has a unique signature as it passes the limb of the star. There are other signatures as well. The data needs to be “crunched.”

LC

Good question.

I don’t know if any has been ruled _out_ yet (which is something like ~ 10 % chance), but planets have been ruled in, validated.

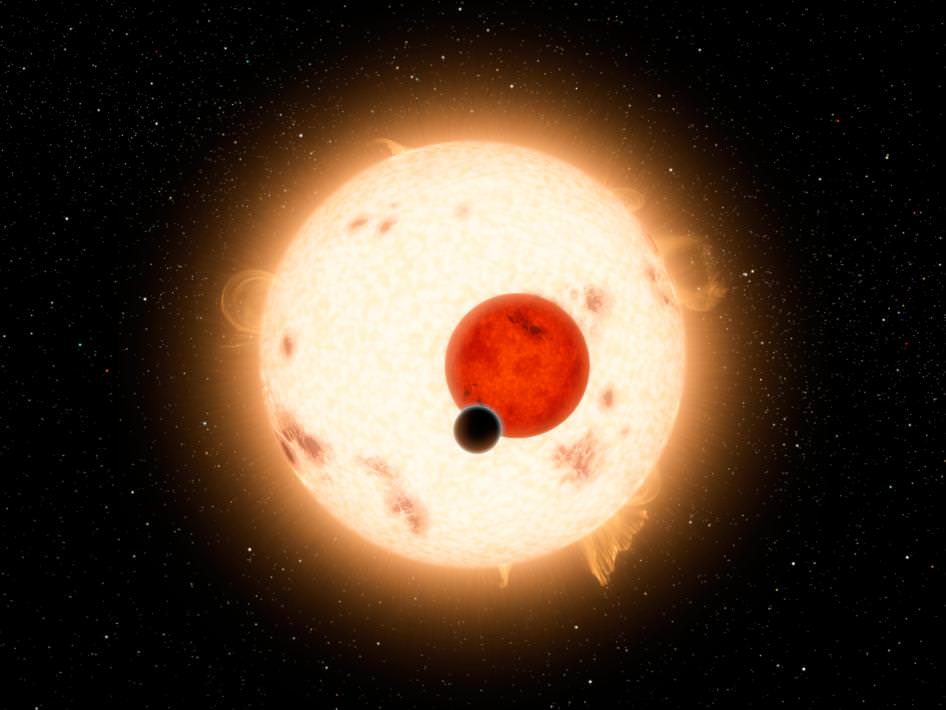

Those are the KOI (Kepler Objects of Interest) candidates that are moved to exoplanets status signified with a naming, Kepler-nm. For example Kepler-16b above.

All exoplanets are validated by having two independent experiments showing them.

Failing that, they can be ruled out in time. Often the repeat younger experiment have larger sensitivity, so is more likely the best observation. Sometimes I believe they have found what trigged the first experiment in believing it was a planet. And other times it turns out a planet candidate is actually a brown dwarf or at least a BD candidate.

In some few cases that have been Kepler itself, as it turned out systems could be so packed that the planets tugged at each other. That made an independent observation of transit time changes besides the primary transit observation.

But most will need other observatories painstakingly checking up on Kepler.

Yo Paul, at the first paragraph, there’s a rogue apostrophe in the fifth line: “It’s primary goal…”

Also, there’s a rogue letter “T” at the end of that paragraph.

I’ve fixed it, but It actually wasn’t like that initially when I posted the article; Nancy had done a final edit as usual. Mistakes happen…

Ever since Eve was at the tree of knowledge, men have always blamed the woman! 😉

P.S. The next time there are some typos, I’ll send an e-mail to Nancy!

We need multiple years of observation to get enough transits to detect the small planets further out. This seems like a no-brainer.

It could turn out that extending Kepler’s mission would be the single most significant investment that our species makes.

Signficant maybe, but I think the best investment we could make at the moment would be making our own planetary presence a little more sustainable in the long-term.

Now that we have passed “peak child” some 20 years hence, the rest of the population pyramid is filling out. Two more generations to go, i.e at the end of this century we will have stabilization at some ~ 9-10 Gpeople.

I would say that the population stabilization is the most important factor that we needed and now will have. Hans Rosling keeps statistics on these things, and it turns out if I understood correctly that the diminishing poverty was the largest contributing factor for stabilization. When women lives in decent conditions and have access to child control, they choose smaller families because it optimizes good living.

IIRC Rosling said the other week in an interview (I forgot where, but it should be googeable) that no doubt the large population will be a challenge, but that we could still minimize the maximum by fighting poverty.* Democracy and free markets is AFAIK essential, but social medicine and directed aid helps. Rosling himself said most nations will do well, but there are still stragglers: Afghanistan and some few african nations that isn’t in on the continent’s rapid economical rise.

If you can get UN and ISAF to pull out of Afghanistan anytime soon and concentrate on aid instead instead of security, that may be a good thing.

——————-

* He didn’t say it explicitly, but I believe he implied a need to keep the population stable there if we can. To have a sustainable resource utilization the next largest factor is to optimize efficiency, and AFAIU the stats innovation and markets have both benefited from more people.

Maybe one day the population will slowly decrease, but I don’t think there ever will be any incentive to actively push for that.

I just like the picture, it looks like a fish

Atleast the big star does

I’m keeping my focal axes crossed for this one.

Incidentally, one reason that Kepler not only want more time but _need_ more time is that it turns out our own star is rather less jittery than most. Kepler is also the first mission to characterize star jitter, outside of our Sun, this thoroughly I believe:

“The Kepler spacecraft has hit an unexpected obstacle as it patiently watches the heavens for exoplanets: too many rowdy young stars. The orbiting probe detects small dips in the brightness of a star that occur when a planet crosses its face. But an analysis of some 2,500 of the tens of thousands of Sun-like stars detected in Kepler’s field of view has found that the stars themselves flicker more than predicted, with the largest number varying twice as much as the Sun. That makes it harder to detect Earth-sized bodies.

As a result, the analysis suggests that Kepler will need more than double its planned mission life of three-and-a-half years to achieve its main goal of determining how common Earth-like planets are in the Milky Way. […]

“It would be a real shame” if NASA ends the mission “just as Kepler is on the threshold of answering it”.” [Nature, 6 September 2011.]

Yeah, totally extend it, it’s a mindbowling mission.