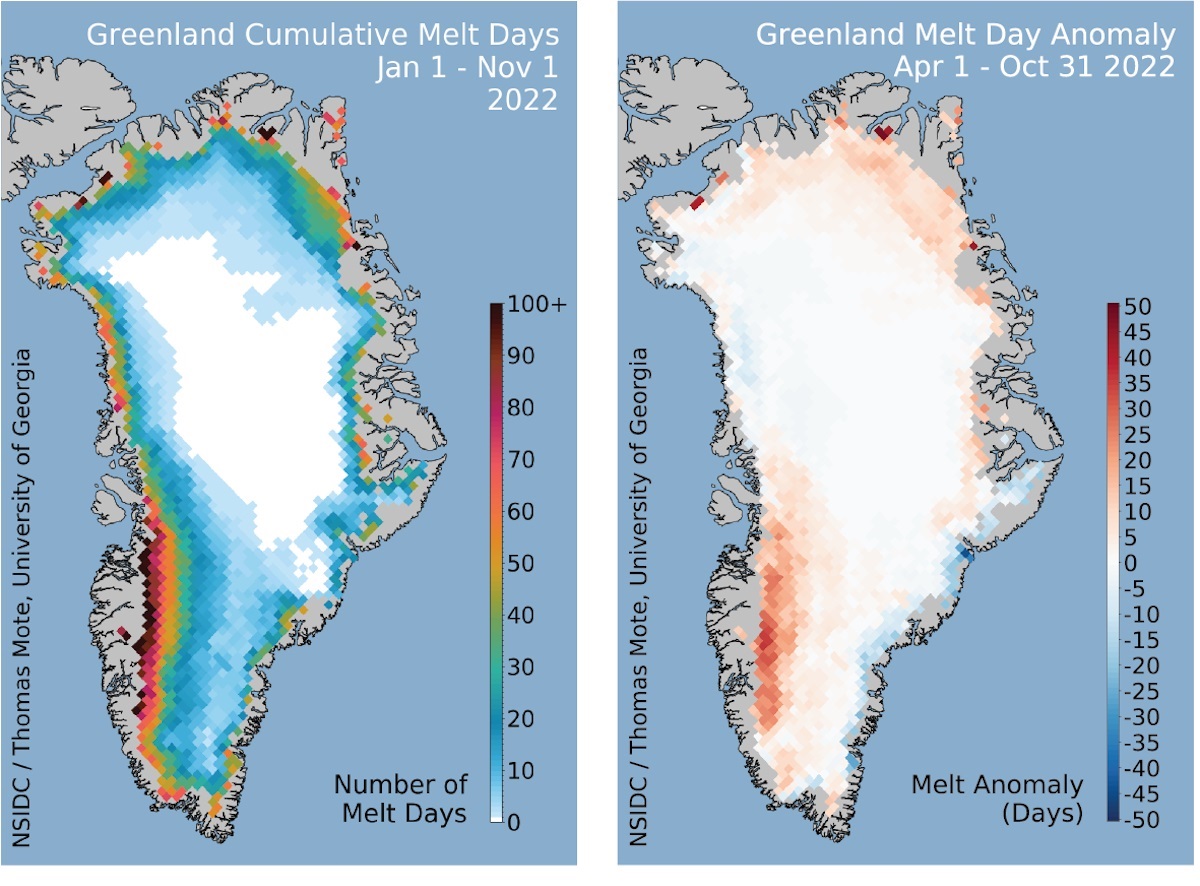

Climate change is the single greatest threat facing our planet today. Thanks to excess carbon emissions that have been growing steadily since the mid-20th century, average temperatures continue to rise worldwide. This leads to feedback mechanisms, such as rising sea levels, extreme weather, drought, wildfires, and glacial melting. This includes the Arctic Ice Pack, the East Antarctic glacier, and the Greenland Ice Sheet (GrIS), which are rapidly melting and increasing global sea levels.

Worse than that, the disappearance of the world’s ice sheets means that Earth’s surface and oceans absorb more heat, driving global temperatures even further. According to a new NASA-supported study by an international team of Earth scientists and glaciologists, the Greenland Ice Sheet is melting at an accelerating rate, much faster than existing models predict. According to these findings, far more ice will be lost from Greenland during the 21st century, which means its contribution to sea-level rise will be significantly higher.

The team consisted of researchers from the National Space Institute at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU Space), the Glaciology Section at the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI), the Institut des Géosciences de l’Environnement at the Université Grenoble Alpes, the University of Copenhagen, Dartmouth College, University of California Irvine (UC Irvine), and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (NASA JPL). Their paper, titled “Extensive inland thinning and speed-up of Northeast Greenland Ice Stream,” recently appeared in Nature.

Located in northeast Greenland, the Zachariae Isstrom glacier (Isstrøm meaning “ice stream” in Danish) has been steadily melting for the past two decades. In 2012, the floating extensions collapsed, and this glacier has since retreated inland at an accelerating pace. Due to the low levels of precipitation in this region (known as the “Arctic desert”), the ice sheet is not regenerating enough to mitigate this melt. However, scientists have had difficulty measuring how much ice is lost a year since the ice sheet’s interior – which moves less than one meter (3.3 feet) per year – is difficult to monitor.

Nevertheless, previous models that estimated the amount of ice lost appeared to have vastly underestimated the problem. According to Shfaqat Abbas Khan, a DTU Space professor, and the study’s lead author, the situation is significantly worse. “Our previous projections of ice loss in Greenland until 2100 are vastly underestimated,” he said. “Models are mainly tuned to observations at the front of the ice sheet, which is easily accessible, and where, visibly, a lot is happening.”

The NASA-supported study is partly based on data collected by the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), a network of precise GPS stations reaching as far as 200 km (124 mi) inland on the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream. This was combined with high-resolution numerical modeling and surface-elevation data obtained by the ESA’s CryoSat-2 satellite, an Earth Explorer Mission (EEM) dedicated to measuring polar sea ice thickness and monitoring changes in ice sheets. As Khan explained:

“Our data show us that what we see happening at the front reaches far back into the heart of the ice sheet. We can see that the entire basin is thinning, and the surface speed is accelerating. Every year the glaciers we’ve studied have retreated further inland, and we predict that this will continue over the coming decades and centuries. Under present-day climate forcing, it is difficult to conceive how this retreat could stop.”

Study co-author Mathieu Morlighem, a professor of earth sciences at Dartmouth College, said:

“It is truly amazing that we are able to detect a subtle speed change from high-precision GPS data, which ultimately, when combined with a model of ice flow, inform us on how the glacier slides on its bed. It is possible that what we find in northeast Greenland may be happening in other sectors of the ice sheet. Many glaciers have been accelerating and thinning near the margin in recent decades. GPS data helps us detect how far this acceleration propagates inland, potentially 200-300 km from the coast. If this is correct, the contribution from ice dynamics to the overall mass loss of Greenland will be larger than what current models suggest.”

According to their results, the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream will add between 13.5 to 15.5 mm by 2100 – six times higher than previous models suggested. This is equivalent to the Greenland ice sheet’s contribution to the North Atlantic for the past 50 years. According to the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), global sea levels are expected to rise by 22 to 98 cm (8.66 to 35.58 inches) by the end of the century.

But as more precise observations of changes in ice velocity are included in climate models, these estimates will likely need to be adjusted upwards. Said co-author Eric Rignot, professor of Earth system science at the UC Irvine:

“We foresee profound changes in global sea levels, more than currently projected by existing models. Data collected in the vast interior of ice sheets, such as those described herein, help us better represent the physical processes included in numerical models and in turn provide more realistic projections of global sea-level rise.”

Further Reading: Eurekalert, Nature