The Cartwheel Galaxy, also known as ESO 350-40, is one disturbed-looking piece of cosmic real estate. To look at it now, especially in the latest JWST view, you’d never know it used to be a gorgeous spiral galaxy. That was before it got involved in a head-on collision with a companion. The encounter happened somewhere around 200-300 million years ago. Essentially, the smaller galaxy “bulls-eyed” the Cartwheel, right through its heart. A shock wave swept through the system, changing everything. The aftermath is what we see in this latest image from JWST.

Exploring the Cartwheel

When galaxies collide, interesting things happen. The gravity of two such massive objects colliding (or even passing near each other) distorts the shape of each galaxy. Shock waves ripple through the participants, setting off bursts of star formation. In extreme circumstances, as we see here, the result is a rare ring-type galaxy.

The Cartwheel Galaxy may look amazingly weird (and it is). But, it’s also a great example of galactic wreckage that will eventually fix itself. In a few million years, this scene could look strikingly different. That’s one reason why astronomers are so interested in it. It’s not often they get to see the evolution of a collision like this. The latest view of it is worth digging into, just to look at the amazing detail JWST provided. There’s not just the main Cartwheel, but also other companion galaxies. (The galaxy that plowed through the main one is not in this view.) More on all those in a minute.

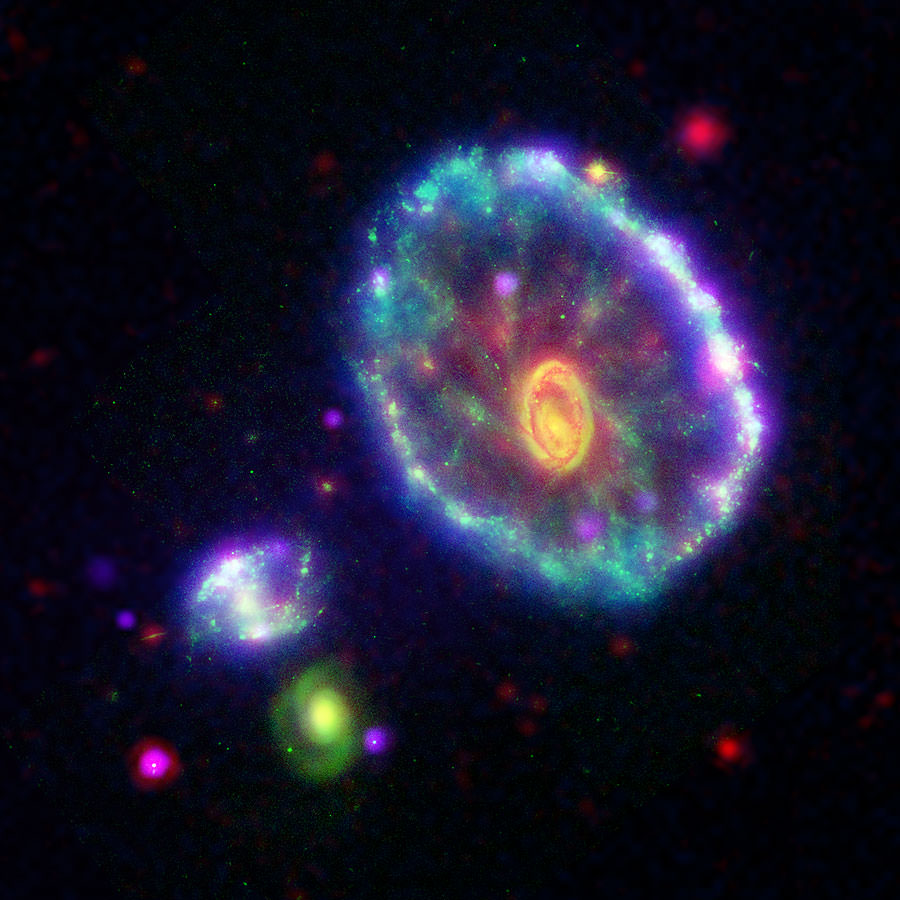

The obvious wreckage from the collision consists of two glowing rings, an inner and an outer one. The inner ring hosts a bright nucleus that’s home to a supermassive black hole. That’s surrounded by a smaller ring of gas and hot dust. Then there’s the outer ring. It has actually expanded so much since the collision that it’s bigger than our Milky Way Galaxy. It’s buzzing with star-forming regions, set off by shock waves from the collision and the expansion of the ring into surrounding regions of gas and dust.

Connecting the two main rings is a set of spooky-looking spokes radiating out from the core. These are likely the ancient spiral arms from the original galaxy going through a reforming process. They, too, are alive with star birth nurseries. The bluish regions are young stars formed as a result of the collision.

JWST Senses Dust

Now, there’s a lot in the Cartwheel that you don’t see if you look at it in visible light. But, turn an infrared-sensitive telescope loose on it, and you find out the Cartwheel is a very dusty place. Clouds of dust obscure the view of some parts of the galaxy. However, all is not lost. Some wavelengths of infrared penetrate through dust. Also, dust radiates heat, which is “visible” in infrared wavelengths. That’s where the JWST’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) comes in handy. In a sense, it can “see” right through the dust. And, it can also detect dust clouds scattered throughout the Cartwheel. For example, that’s how we get to see so many star-forming regions in great detail.

To really dig into the details of the dust that permeates this galaxy, JWST’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) essentially did a little chemical analysis. It turns out that regions in the spokes are rich in hydrocarbons and other compounds, as well as silica dust. MIRI also produces information regarding the distances of galaxies in the background. The closest galaxies are in blue and the farthest are in green and red. The different colors are due to bright emissions from dust being redshifted by the expansion of the universe.

Setting the Scene at the Cartwheel

The Cartwheel doesn’t travel alone. It’s part of a four-galaxy Cartwheel Group that lies about 500 million light-years away from us. The companion galaxies are much smaller and are all physically linked together with the Cartwheel. There’s a small, blue Magellanic Cloud-type galaxy, called G1. Nearby lies a small, yellow compact spiral called G2. These two smaller ones show a lot of star formation. The lower galaxy also glows due to the presence of a supermassive black hole. The fourth member (not seen in the JWST image) is a distant spiral called G3. It has a tidal tail stretching out away from it back toward the Cartwheel. It could be the galaxy that plowed through the Cartwheel and caused all the havoc.

When astronomers put together all the imaging data from JWST, they see this scene is just a snapshot in time. The Cartwheel is changing, expanding, and reforming itself. What will happen to it as it changes? The cartwheel-like structure will likely disintegrate as the gas and dust fall back in toward the center. If the other companion galaxies don’t interfere, then perhaps a few hundred million years from now, the Cartwheel will be a beautiful spiral once more.

Checking Out the Cartwheel Before JWST

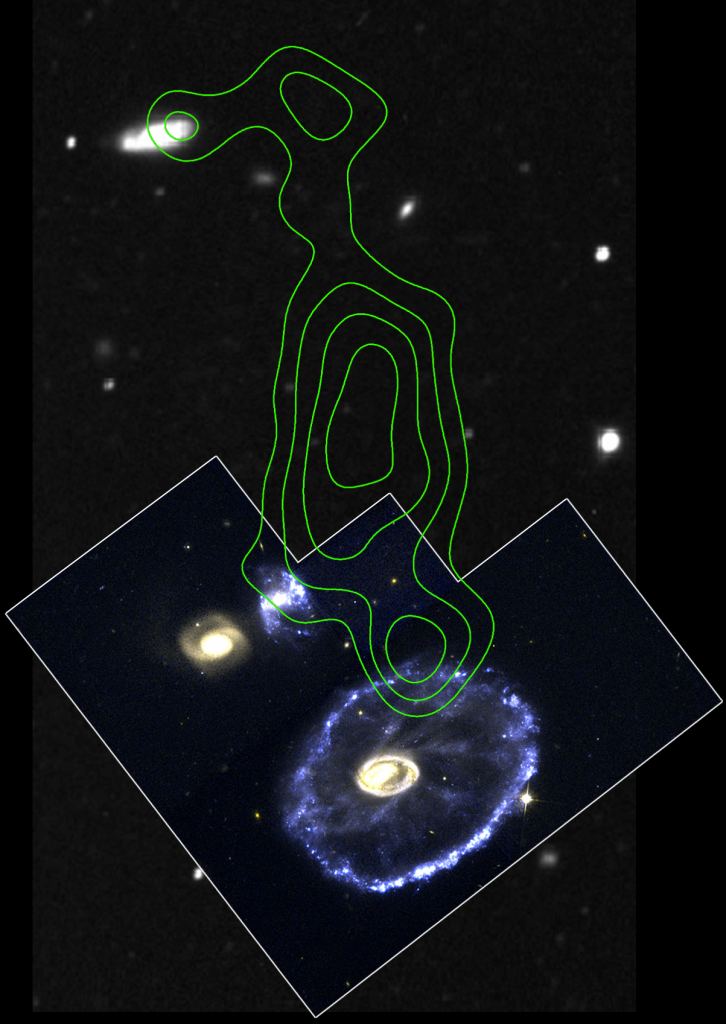

This isn’t the first time a space observatory has taken a look at the Cartwheel group. Hubble Space Telescope captured a view of it in 1995, using the newly installed Wide-Field Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2) instrument. It was the first time such a high-resolution image of the scene of the collision had been taken. XMM-Newton also studied this scene, and it has been detected and mapped in radio frequencies by the Paul Wild Observatory at Narrabri in Australia.

In 2006, NASA unveiled a multi-wavelength image of the Cartwheel Group. It was created using data from Hubble Space Telescope, the Galaxy Evolution Explorer (in ultraviolet light), the Spitzer Space Telescope (in infrared), and the Chandra X-Ray Observatory. In particular, the Chandra data revealed a number of bright x-ray sources in the Cartwheel that likely indicate the presence of stellar black holes. That’s not surprising in a region that is alive with the formation of massive stars that die quickly as supernovae.

It’s likely that the Cartwheel will come in for more studies with both Earth-based and ground-based observatories, and in particular with JWST. It’s a dynamic scene of galaxy evolution that astronomers can use to learn more about the physics and astrophysics of galactic mergers and encounters.

For More Information

Webb Captures Stellar Gymnastics in the Cartwheel Galaxy