On July 2nd, 1967, the U.S. Vela 3 and 4 satellites noticed something rather perplexing. Originally designed to monitor for nuclear weapons tests in space by looking for gamma radiation, these satellites picked up a series of gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) coming from deep space. And while decades have passed since the “Vela Incident“, astronomers are still not 100% certain what causes them.

One of the problems has been that until now, scientists have been unable to study gamma ray bursts in any real capacity. But thanks to a new study by an international team of researchers, GRBs have been recreated in a laboratory for the first time. Because of this, scientists will have new opportunities to investigate GRBs and learn more about their properties, which should go a long away towards determining what causes them.

The study, titled “Experimental Observation of a Current-Driven Instability in a Neutral Electron-Positron Beam“, was recently published in the Physical Review Letters. The study was led by Jonathon Warwick from Queen’s University Belfast and included members from the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, The John Adams Institute for Accelerator Science, the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, and multiple universities.

Until now, the study of GRBs have been complicated by two major issues. On the one hand, GRBs are very short lived, lasting for only seconds at a time. Second, all detected events have occurred in distant galaxies, some of which were billions of light-years away. Nevertheless, there are a few theories as to what could account for them, ranging from the formation of black holes and collisions between neutron stars to extra-terrestrial communications.

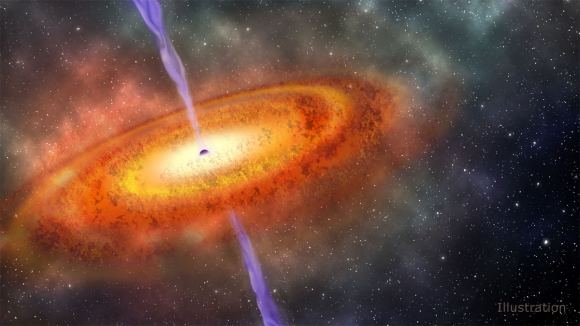

For this reason, investigating GRBs is especially appealing to scientists since they could reveal some previously-unknown things about black holes. For the sake of their study, the research team approached the question of GRBs as if they were related to the emissions of jets of particles released by black holes. As Dr. a lecturer at Queen’s University Belfast, explained in a recent op-ed piece with The Conversation:

“The beams released by the black holes would be mostly composed of electrons and their “antimatter” companions, the positrons… These beams must have strong, self-generated magnetic fields. The rotation of these particles around the fields give off powerful bursts of gamma ray radiation. Or, at least, this is what our theories predict. But we don’t actually know how the fields would be generated.”

With the assistance of their collaborators in the US, France, the UK and Sweden, the team from Queen’s University Belfast relied on the Gemini laser, located at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the UK. With this instrument, which is one of the most powerful lasers in the world, the international collaboration sought to create the first small scale replica of GRBs.

By shooting this laser onto a complex target, the team was able to create miniature versions of these ultra-fast astrophysical jets, which they recorded to see how they behaved. As Dr. Sarri indicated:

“In our experiment, we were able to observe, for the first time, some of the key phenomena that play a major role in the generation of gamma ray bursts, such as the self-generation of magnetic fields that lasted for a long time. These were able to confirm some major theoretical predictions of the strength and distribution of these fields. In short, our experiment independently confirms that the models currently used to understand gamma ray bursts are on the right track.”

This experiment was not only important for the study of GRBs, it could also advance our understanding about how different states of matter behave. Basically, almost all phenomena in nature come down to the dynamics of electrons, as they are much lighter than atomic nuclei and quicker to respond to external stimuli (such as light, magnetic fields, other particles, etc).

“But in an electron-positron beam, both particles have exactly the same mass, meaning that this disparity in reaction times is completely obliterated,” said Dr. Sarri. “This brings to a quantity of fascinating consequences. For example, sound would not exist in an electron-positron world.”

In addition, there is the aforementioned argument that GRBs could in fact be evidence of Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (ETI). In the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI), scientists look for electromagnetic signals that do not appear to have natural explanations. By knowing more about different types of electromagnetic bursts, scientists could be better able to isolate those for which there are no known causes. As Dr. Sarri put it:

“Of course, if you put your detector to look for emissions from space, you do get an awful lot of different signals. If you really want to isolate intelligent transmissions, you first need to make sure all the natural emissions are perfectly known so that they can excluded. Our study helps towards understanding black hole and pulsar emissions, so that, whenever we detect anything similar, we know that it is not coming from an alien civilization.”

Much like research into gravitational waves, this study serves as an example of how phenomena that were once beyond our reach is now open to study. And much like gravitational waves, research into GRBs is likely to yield some impressive returns in the coming years!

Further Reading: The Conversation, Physical Review Letters