What springs to mind when we think of the most commonly-known stars in the night sky? Chances are, it would be stars like Sirius, Vega, Deneb, Rigel, Betelgeuse, Polaris, and Arcturus – all of which derive their names from Arabic, Greek or Latin origins. Much like the constellations, these names have been passed down from one astronomical tradition to another and were eventually adopted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

But what about the astronomical traditions of Earth’s many, many other cultures? Don’t the names they applied to heavens also deserve mention? According to the IAU, they do indeed! After a recent meeting by the Working Group on Star Names (WGSN), the IAU formally adopted 86 new names for stars drawn largely from the Australian Aboriginal, Chinese, Coptic, Hindu, Mayan, Polynesian, and South African peoples.

The WGSN is an international group of astronomers tasked with cataloging and standardizing the star names used by the international astronomical community. This job entails establishing IAU guidelines for the proposals and adoption of names, searching through international historical and literary sources for star names, adopting names of unique historical and cultural value, and maintaining and disseminating the official IAU star catalog.

Last year, the WGSN approved the names for 227 stars. With these latest additions, the catalog now contains the names of 313 stars. Unlike standard star catalogs containing millions or billions of stars designated using strings of letters and numbers, the IAU star catalog consists of bright stars with proper names derived from historical and cultural sources. As Eric Mamajek, chair and organizer of the WGSN, indicated in an IAU press release:

“The IAU Working Group on Star Names is researching traditional star names from cultures around the world and adopting unique names and spellings to avoid confusion in astronomical catalogues and star atlases. These names help ensure that intangible astronomical heritage from skywatchers around the world, and across the centuries, are preserved for use in an era of exoplanetary systems.”

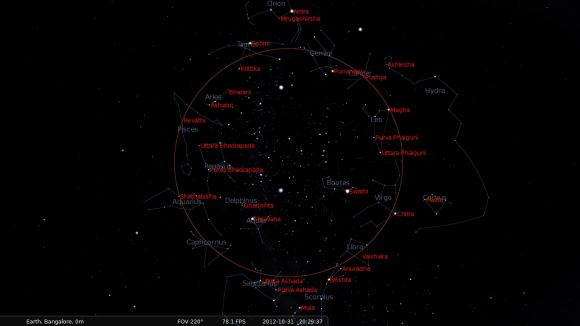

A total of eleven Chinese star names were incorporated into the catalog, three of which are derived from the “lunar mansions” of traditional Chinese astronomy. This refers to vertical strips of the sky that act as markers for the progress of the Moon across the sky in the course of a year. In this sense, they provide a basis for the lunar calendar in the same way that the zodiac worked for Western calendars.

Two names were derived from the ancient Hindu lunar mansions as well. These stars are Revati and Bharani, which designate Zeta Piscium and 41 Arietis, respectively. In addition to being a lunar mansion, Revati was also the daughter of King Kakudmi in Hindu mythology and the consort of the God Balarama – the elder brother of Krishna. On the other hand, Bharani is the name for the second lunar mansion in Hindu astronomy and is ruled by Shurka (Venus).

Beyond the astronomical traditions of India and China, there are also two names adopted from the Khoikhoi people of South Africa and the people of Tahiti – Xamidimura and Pipirima. These names were approved for Mu¹ and Mu² Scorpii, the stars that make up a binary system located in the constellation of Scorpius. Xamidimura is derived from the Khoikhoi name for the star xami di mura – literally “eyes of the lion.”

Pipirima refers to the inseparable twins from Tahitian mythology, a boy and a girl who ran away from their parents and became stars in the night sky. Then you have the Yucatec Mayan name Chamukuy, a small bird that now designates the star Theta-2 Tauri, which is located in the Hyades star cluster in Taurus.

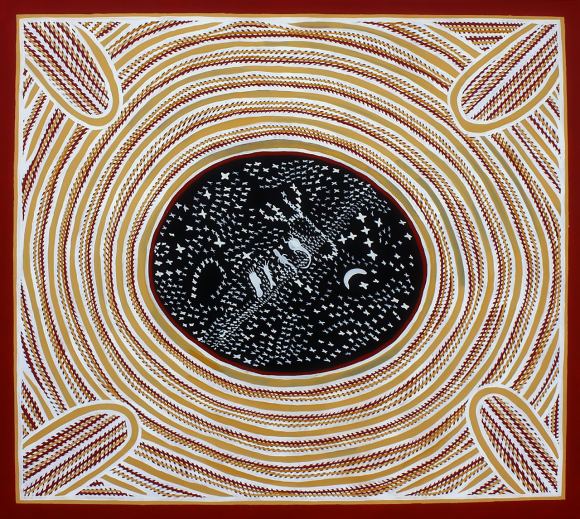

Four Aboriginal Australian star names were also added to the catalog, including the Wardaman names Larawag, Ginan, and Wurren and the Boorong name Unurgunite. These names now designate Epsilon Scorpii, Epsilon Crucis, Zeta Pheonicis, and Sigma Canis Majoris, respectively. Given that Aboriginal Australians have traditions that go back as far as 65,000 years, these names are some of the oldest in existence.

The brightest star to receive a new name was Alsephina, which was given to the star previously designated as Delta Velorum. The name stems from the Arabic name al-safinah (“the ship”), which refers to the ancient Greek constellation Argo Navis (the ship of the Argonauts). This name goes back to the 10th-century Arabic translation of the Almagest, which was compiled by Ptolemy in the 2nd century CE.

The new catalog also includes Barnard’s Star, a name that has been in common usage for about a century but was never an official designation. This red dwarf star, which is less than six light-years from Earth, is named after the astronomer who discovered it – Edward Emerson Barnard – in 1916. It now joins Alsafi (Sigma Draconis), Achird (Eta Cassiopeiae), and Tabit (Pi-3 Orionis) as being one of four nearby stars whose proper names were approved in 2017.

One of the hallmarks of modern astronomy is how naming conventions are moving away from traditional Western and Classical sources and broadening to become more worldly. In addition to being a more inclusive, multicultural approach, it reflects the spirit of modern astronomical research and space exploration, which is characterized by international cooperation.

Someday, assuming our progeny ever go forth and begin to colonize distant star systems, we can expect that the stars and planets they come to know will have names that reflect the diverse astronomical traditions of Earth’s many cultures.

Further Reading: IAU