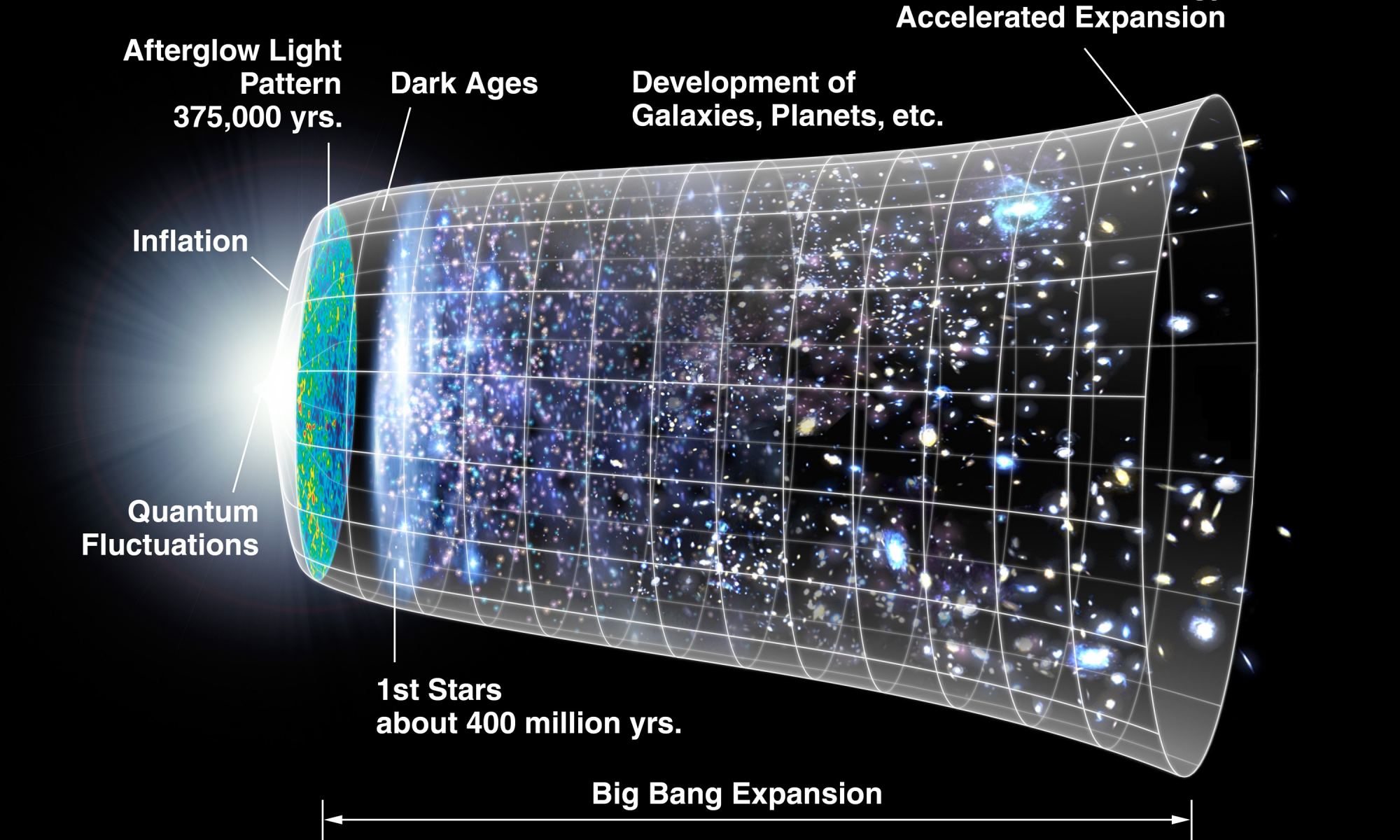

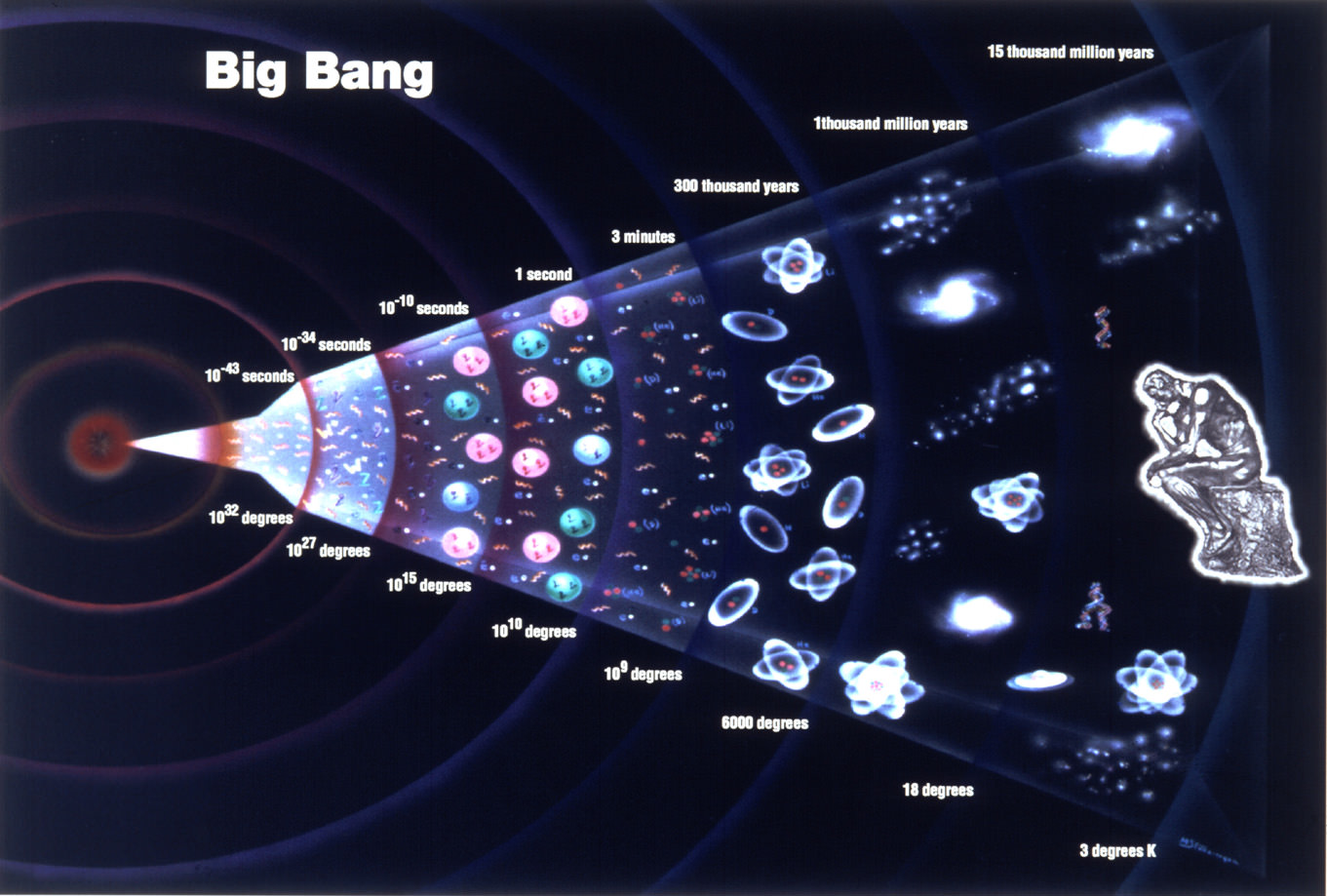

Astronomers are currently pushing the frontiers of astronomy. At this very moment, observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) are visualizing the earliest stars and galaxies in the Universe, which formed during a period known as the “Cosmic Dark Ages.” This period was previously inaccessible to telescopes because the Universe was permeated by clouds of neutral hydrogen. As a result, the only light is visible today as relic radiation from the Big Bang – the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) – or as the 21 cm spectral line created by the reionization of hydrogen (aka. the Hydrogen Line).

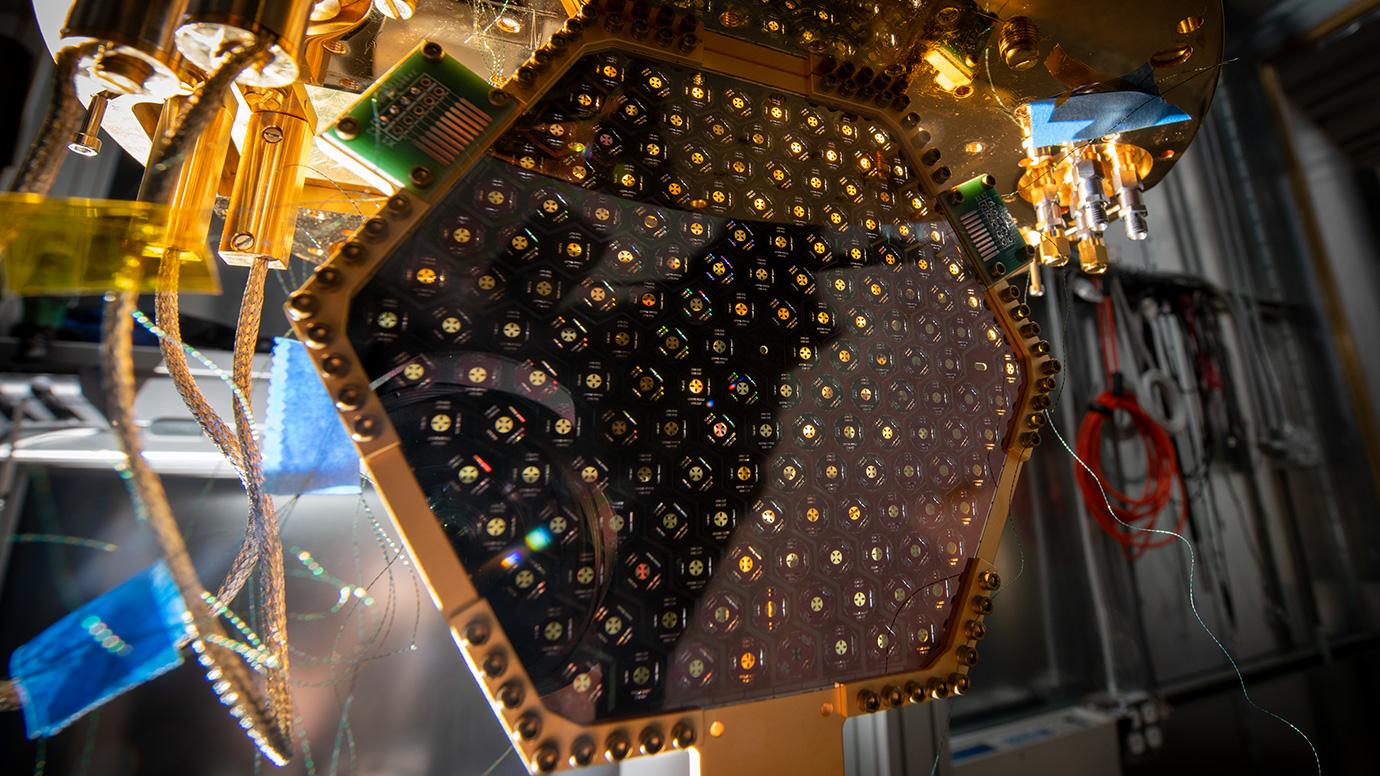

Now that the veil of the Dark Ages is being slowly pulled away, scientists are contemplating the next frontier in astronomy and cosmology by observing “primordial gravitational waves” created by the Big Bang. In recent news, it was announced that the National Science Foundation (NSF) had awarded $3.7 million to the University of Chicago, the first part of a grant that could reach up to $21.4 million. The purpose of this grant is to fund the development of next-generation telescopes that will map the CMB and the gravitational waves created in the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang.

L