[/caption]

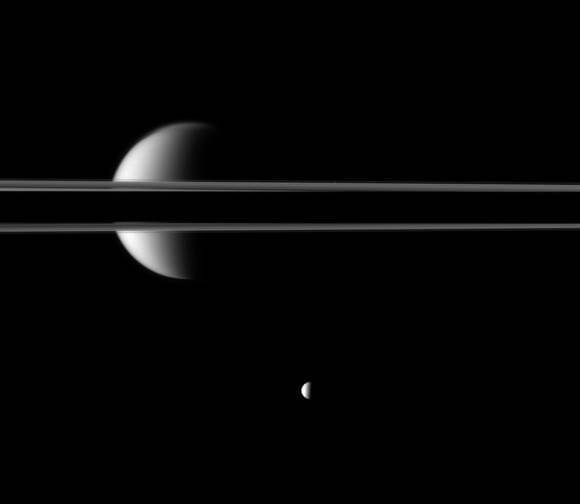

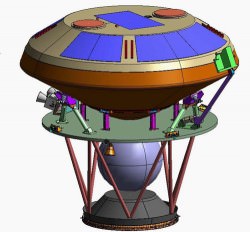

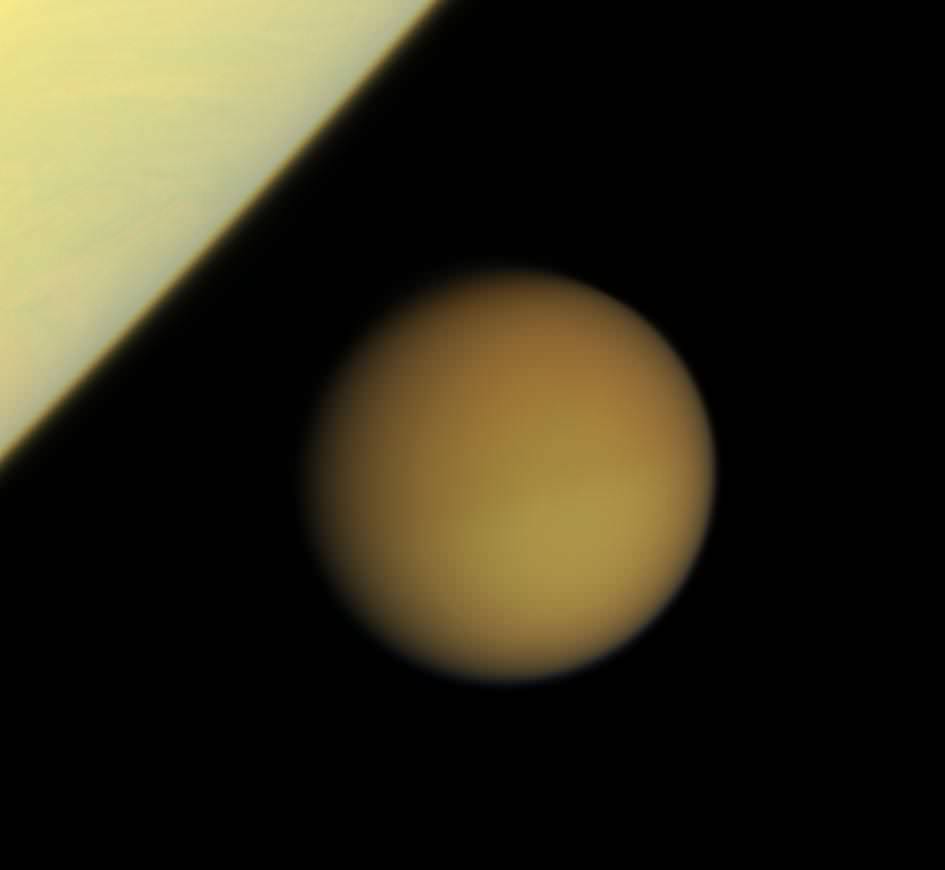

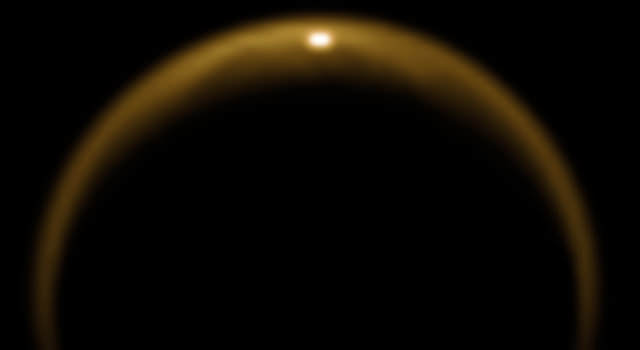

It’s a space navigator’s dream! The Cassini spacecraft will perform close flybys of two of Saturn’s most enigmatic moons all within less than 48 hours, and with no maneuvers in between. Enceladus and Titan are aligned just right so that Cassini can catch glimpses of these two contrasting moons – one a geyser world and the other an analog to early Earth.

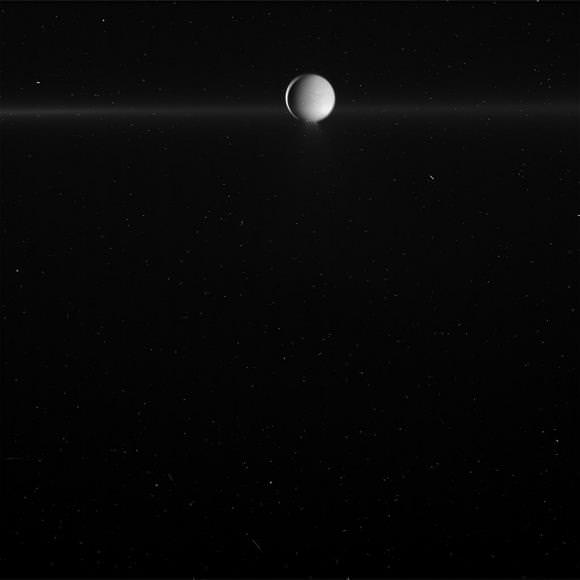

Cassini will make its closest approach to Enceladus late at night on May 17 Pacific time, which is in the early hours of May 18 UTC. The spacecraft will pass within about 435 kilometers (270 miles) of the moon’s surface.

The main scientific goal at Enceladus will be to watch the sun play peekaboo behind the water-rich plume emanating from the moon’s south polar region. Scientists using the ultraviolet imaging spectrograph will be able to use the flickering light to measure whether there is molecular nitrogen in the plume. Ammonia has already been detected in the plume and scientists know heat can decompose ammonia into nitrogen molecules. Determining the amount of molecular nitrogen in the plume will give scientists clues about thermal processing in the moon’s interior.

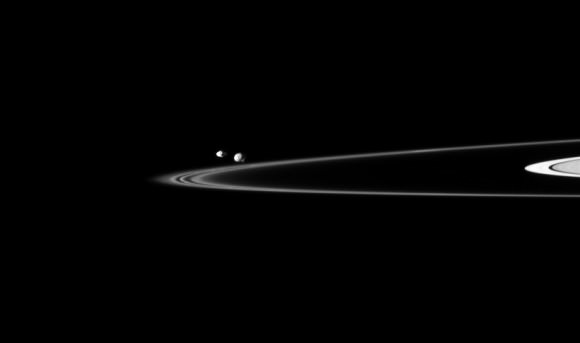

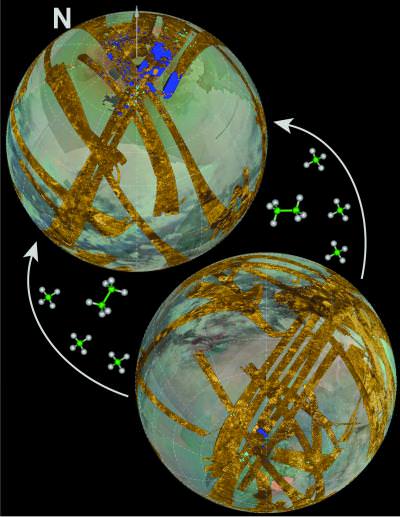

Then on to Titan: the closest approach will take place in the late evening May 19 Pacific time, which is in the early hours of May 20 UTC. The spacecraft will fly to within 1,400 kilometers (750 miles) of the surface.

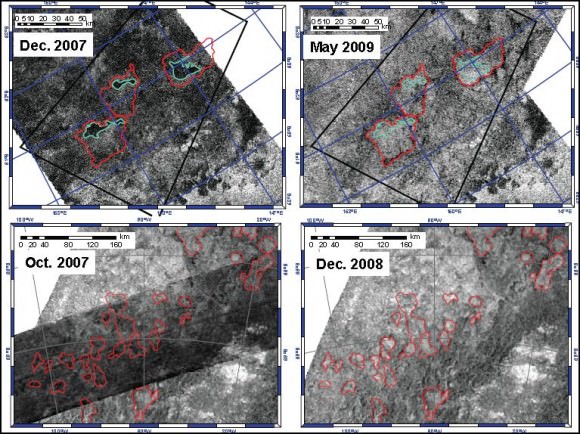

Cassini will primarily be doing radio science during this pass to detect the subtle variations in the gravitational tug on the spacecraft by Titan, which is 25 percent larger in volume than the planet Mercury. Analyzing the data will help scientists learn whether Titan has a liquid ocean under its surface and get a better picture of its internal structure. The composite infrared spectrometer will also get its southernmost pass for thermal data to fill out its temperature map of the smoggy moon.

Cassini has made four previous double flybys and one more is planned in the years ahead.

For more information on the Enceladus flyby, dubbed “E10,” see this link.

For more information on the Titan flyby, dubbed “T68,” see this link.

Source: JPL