[/caption]

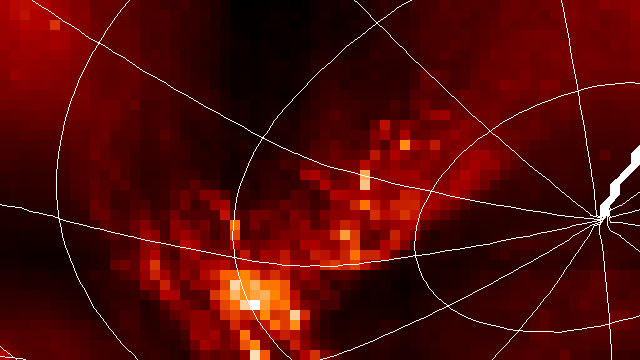

Titan is the only place in the solar system other than the earth that appears to have large quantities of liquid sitting on the surface. Granted, conditions on Titan are quite different than on Earth. For one thing, it’s a lot colder on Titan and the liquids there are various types of hydrocarbons. “Methane is to Titan what water is to the earth,” says astronomer Mike Brown (yes, that guy, of Pluto, Eris and Makemake fame.) But now Brown and his colleagues have discovered another similarity. Titan has fog. “All of those bright sparkly reddish white patches (shown in the image here) are fog banks hanging out at the surface in Titan’s late southern summer,” Brown wrote in his blog.

Wow.

But how does this happen? Fog only usually appears when 1.) there is liquid in the atmosphere (i.e., that means it must be “humid” on Titan) and 2.) the air temperature cools drastically. But Titan’s atmosphere is extremely thick, so it cools slowly. Plus the atmosphere is already really cold and making it colder would be difficult.

“If you were to turn the sun totally off,” said Brown, “Titan’s atmosphere would still take something like 100 years to cool down. And even the coldest parts of the surface are much too warm to ever cause fog to condense.”

So what is going on there?

To get the humidity in Titan’s atmosphere, Brown said the liquid methane must be evaporating.

“Evaporating methane means it must have rained,” he wrote. “Rain means streams and pools and erosion and geology. Fog means that Titan has a currently active methane hydrological cycle doing who knows what on Titan.”

Plus, the only one way to make the fog stick around on the ground for any amount of time is have both humidity and cool air. And the only way to cool the air on Titan is have it in contact with something cold: like a pool of evaporating liquid methane.

Brown said the fog doesn’t appear to be around the just the dark areas near the south pole that likely are hydrocarbon lakes. “It looks like it might be more or less everywhere at the south pole. My guess is that the southern summer polar rainy season that we have witnessed over the past few years has deposited small pools of liquid methane all over the pole. It’s slowly evaporating back into the atmosphere where it will eventually drift to the northern pole where, I think, we can expect another stormy summer season. Stay tuned. Northern summer solstice is in 2016.”

And here comes the fun part (as if fog on Titan wasn’t fun enough!) Brown is looking for a little citizen science help. You can read the paper on this by Brown and his colleagues here. Most peer review is done by one person, and brown would like a few more eyes to see this paper to look for any flaws, and to see if their arguments make sense and are convincing.

Brown says: “I thought I would try an experiment of my own here. It goes like this: feel free to provide a review of my paper! I know this is not for everyone. Send it directly to me or comment here (at his blog). I will take serious comments as seriously as those of the official reviewer and will incorporate changes into the final version of the paper before it is published.

Please, though, serious reviewers only.

Source: Mike Brown’s Blog