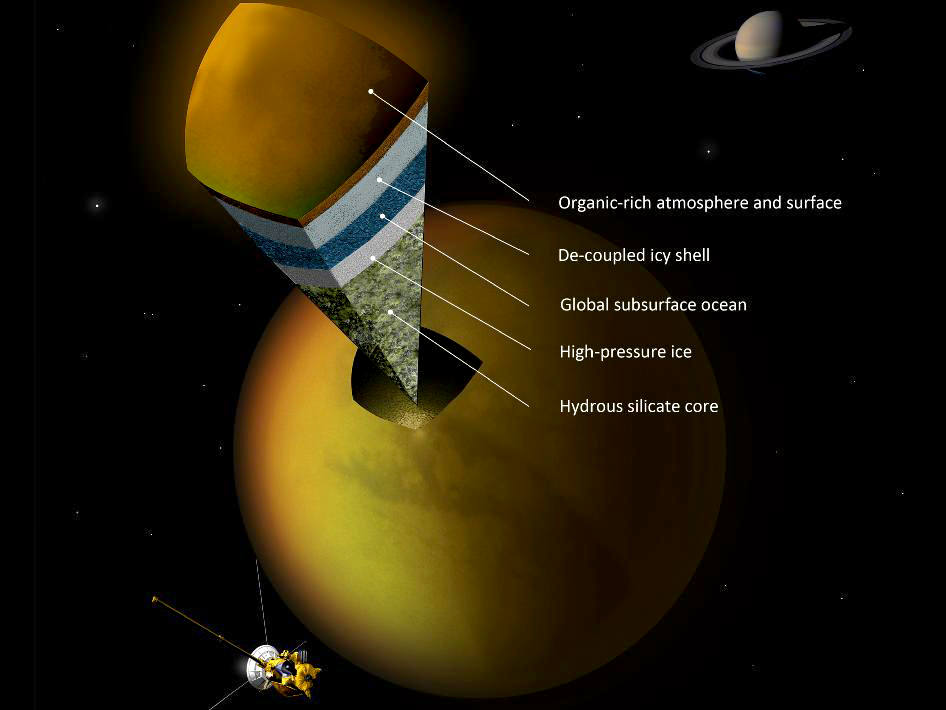

Saturn’s hazy Titan is now on the short list of moons that likely harbor a subsurface ocean of water, based on new findings from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft.

As Titan travels around Saturn during its 16-day elliptical orbits, it gets rhythmically squeezed by the gravitational pull of the giant planet — an effect known as tidal flexing (see video below.) If the moon were mostly composed of rock, the flexing would be in the neighborhood of around 3 feet (1 meter.) But based on measurements taken by the Cassini spacecraft, which has been orbiting Saturn since 2004, Titan exhibits much more intense flexing — ten times more, in fact, as much as 30 feet (10 meters) — indicating that it’s not entirely solid at all.

Instead, Cassini scientists estimate that there’s a moon-wide ocean of liquid water beneath the frozen crust of Titan, possibly sandwiched between layers of ice or rock.

“Short of being able to drill on Titan’s surface, the gravity measurements provide the best data we have of Titan’s internal structure.”

– Sami Asmar, Cassini team member at JPL

“Cassini’s detection of large tides on Titan leads to the almost inescapable conclusion that there is a hidden ocean at depth,” said Luciano Iess, the paper’s lead author and a Cassini team member at the Sapienza University of Rome, Italy. “The search for water is an important goal in solar system exploration, and now we’ve spotted another place where it is abundant.”

Although liquid water is a necessity for the development of life, the presence of it alone does not guarantee that alien organisms are swimming around in a Titanic underground ocean. It’s thought that water must be in contact with rock in order to create the necessary building blocks of life, and as yet it’s not known what situations may exist around Titan’s inner sea. But the presence of such an ocean — possibly containing trace amounts of ammonia — would help explain how methane gets replenished into the moon’s thick atmosphere.

Although liquid water is a necessity for the development of life, the presence of it alone does not guarantee that alien organisms are swimming around in a Titanic underground ocean. It’s thought that water must be in contact with rock in order to create the necessary building blocks of life, and as yet it’s not known what situations may exist around Titan’s inner sea. But the presence of such an ocean — possibly containing trace amounts of ammonia — would help explain how methane gets replenished into the moon’s thick atmosphere.

“The presence of a liquid water layer in Titan is important because we want to understand how methane is stored in Titan’s interior and how it may outgas to the surface,” said Jonathan Lunine, a Cassini team member at Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y. “This is important because everything that is unique about Titan derives from the presence of abundant methane, yet the methane in the atmosphere is unstable and will be destroyed on geologically short timescales.”

The team’s paper appears in today’s edition of the journal Science. Read more on the Cassini mission site here.

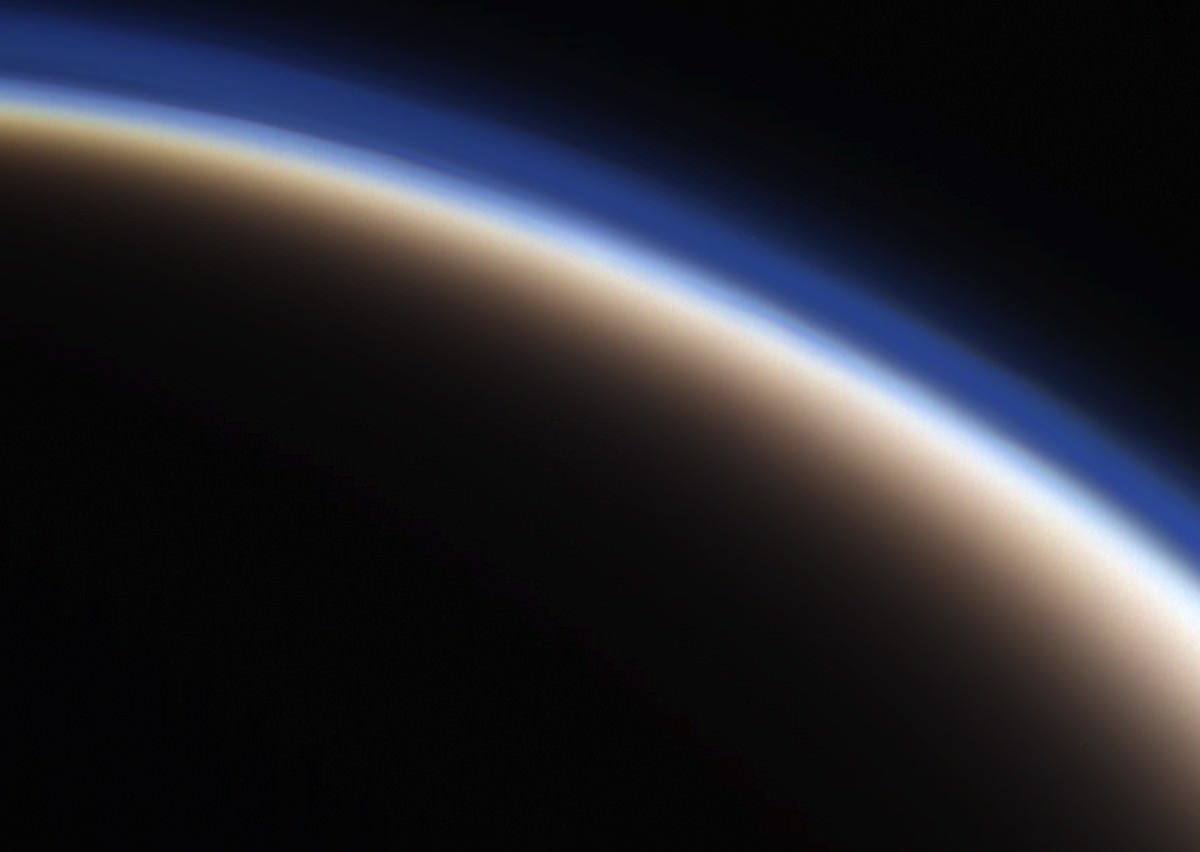

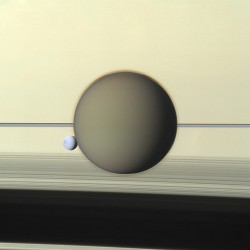

Top image: artist’s concept showing a possible scenario for the internal structure of Titan. (A. Tavani). Side image: An RGB-composite color image of Titan and Dione in front of Saturn’s face and rings, made from Cassini images acquired on May 21, 2011. (NASA/JPL/SSI. Composite by J. Major.)