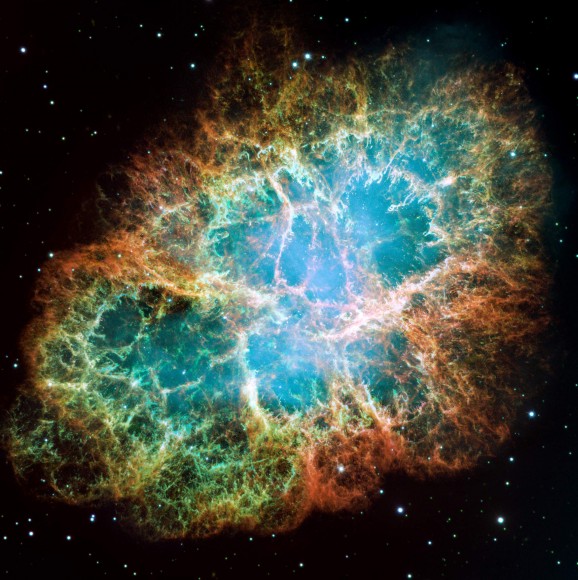

A team of Australian astronomers has been busy utilizing some of the world’s leading radio telescopes located in both Australia and Chile to carve away at the layered remains of a relatively new supernova. Designated as SN1987A, the 28 year-old stellar cataclysm came to Southern Hemisphere observer’s attention when it sprang into action at the edge of the Large Magellanic Cloud some two and a half decades ago. Since then, it has provided researchers around the world with a ongoing source of information about one of the Universe’s “most extreme events”.

Representing the University of Western Australia node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research, PhD Candidate Giovanna Zanardo led the team focusing on the supernova with the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA) in New South Wales. Their observations took in the wavelengths spanning the radio to the far infrared.

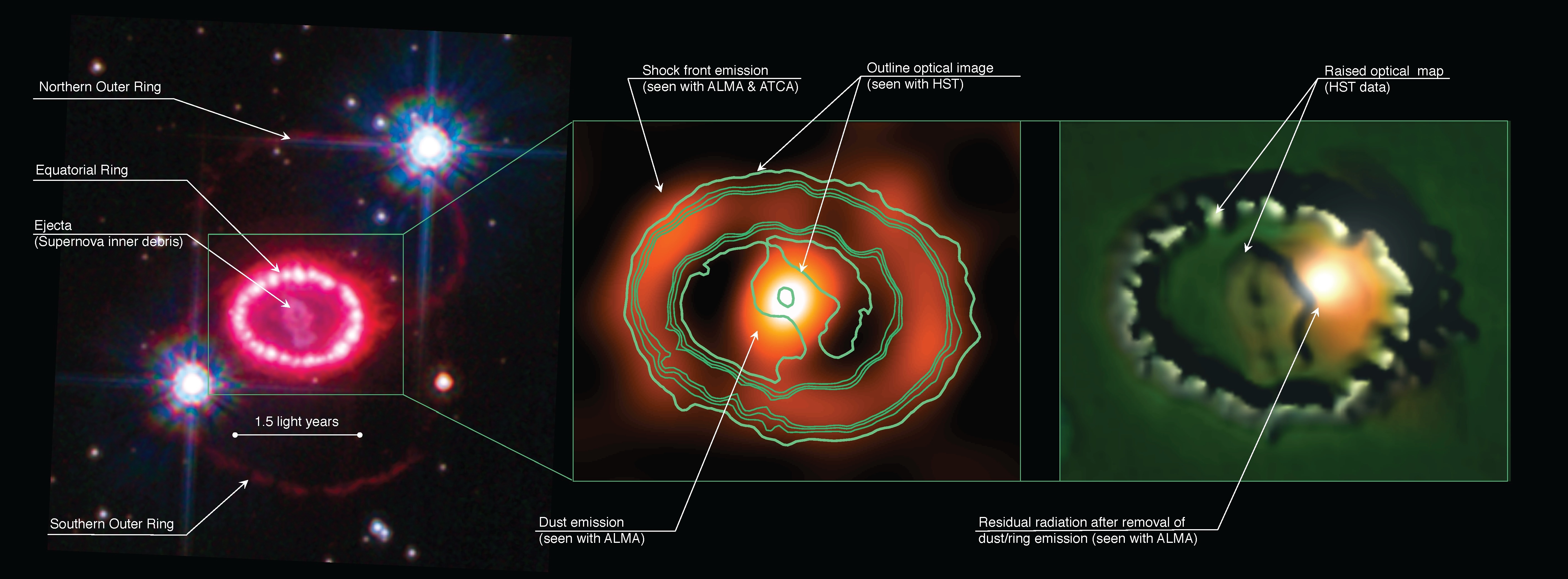

“By combining observations from the two telescopes we’ve been able to distinguish radiation being emitted by the supernova’s expanding shock wave from the radiation caused by dust forming in the inner regions of the remnant,” said Giovanna Zanardo of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) in Perth, Western Australia.

“This is important because it means we’re able to separate out the different types of emission we’re seeing and look for signs of a new object which may have formed when the star’s core collapsed. It’s like doing a forensic investigation into the death of a star.”

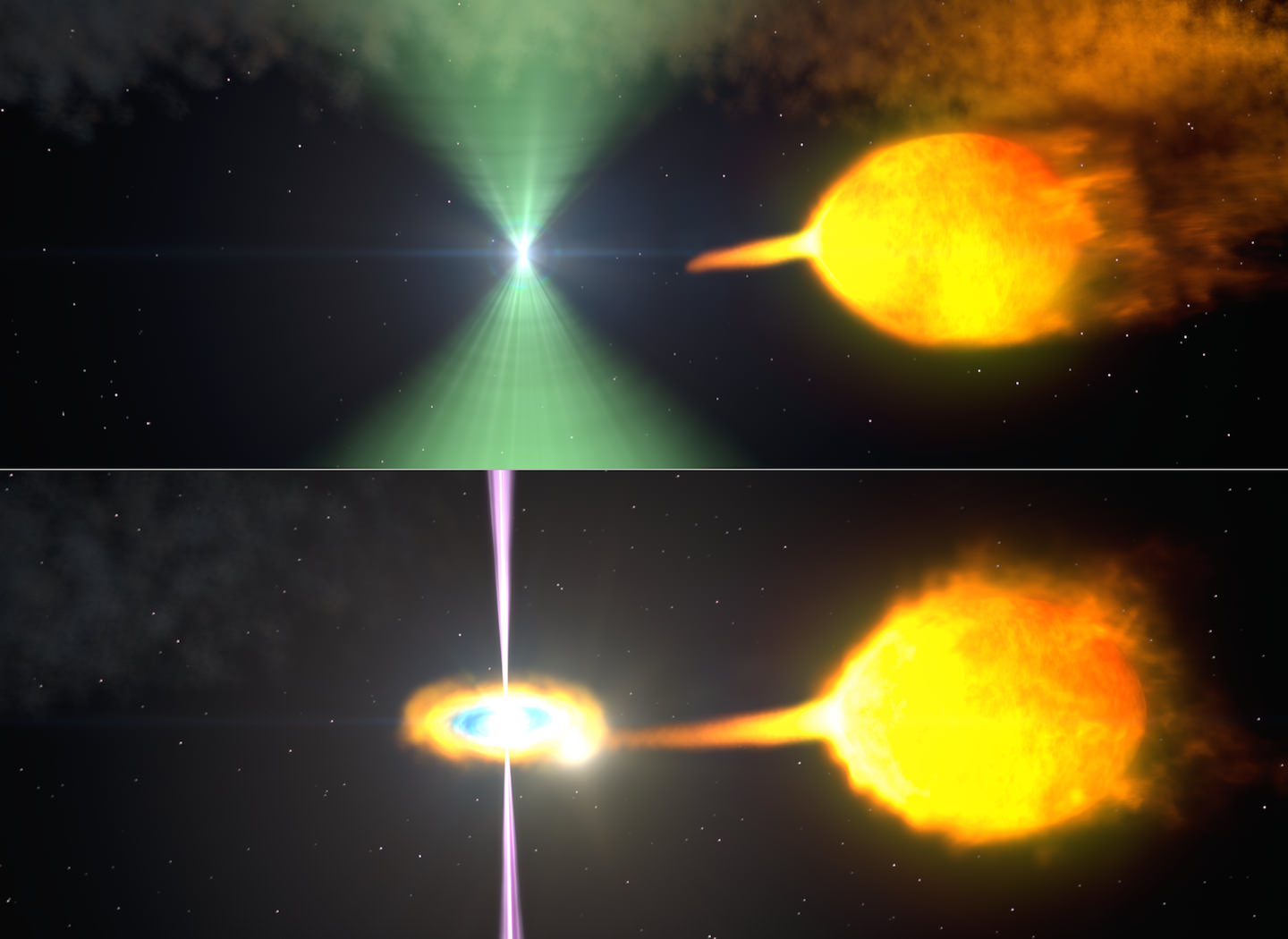

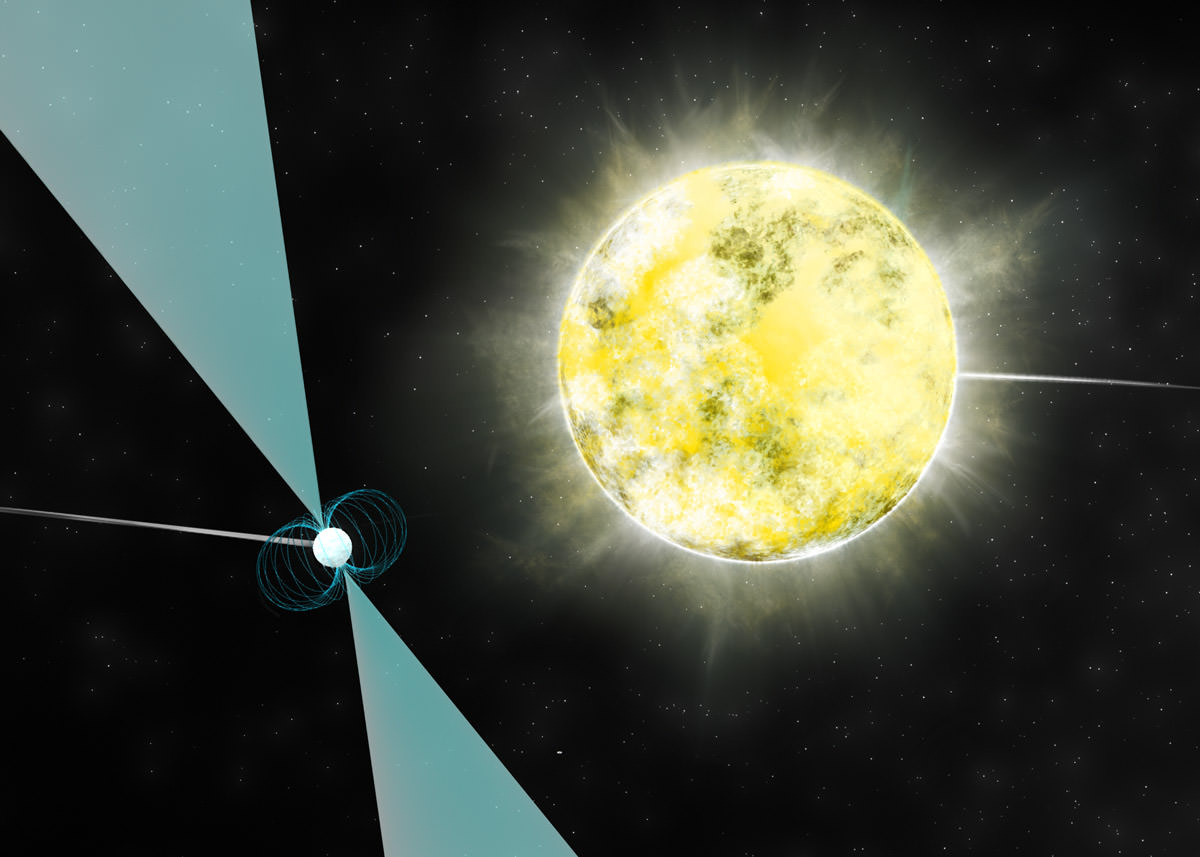

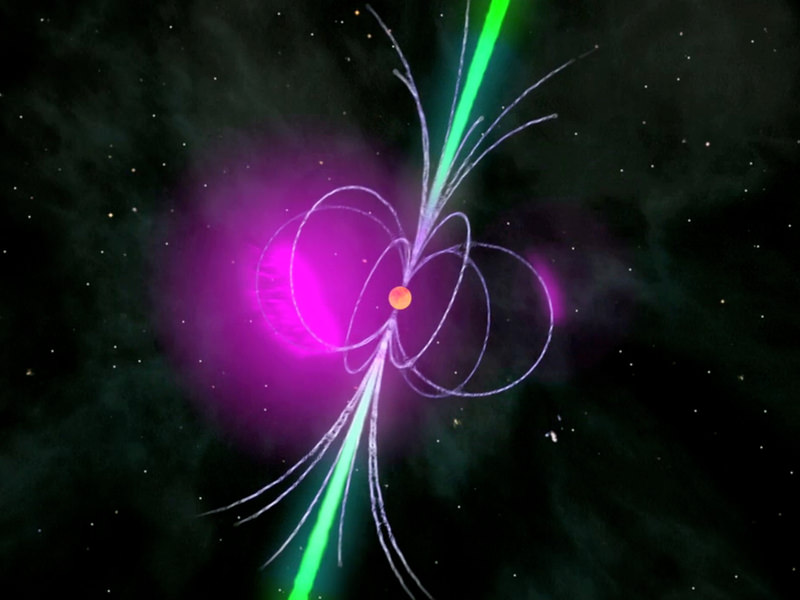

“Our observations with the ATCA and ALMA radio telescopes have shown signs of something never seen before, located at the centre or the remnant. It could be a pulsar wind nebula, driven by the spinning neutron star, or pulsar, which astronomers have been searching for since 1987. It’s amazing that only now, with large telescopes like ALMA and the upgraded ATCA, we can peek through the bulk of debris ejected when the star exploded and see what’s hiding underneath.”

But, there is more. Not long ago, researchers published another paper which appeared in the Astrophysical Journal. Here they made an effort to solve another unanswered riddle about SN1987A. Since 1992 the supernova appears to be “brighter” on one side than it does the other! Dr. Toby Potter, another researcher from ICRAR’s UWA node took on this curiosity by creating a three-dimensional simulation of the expanding supernova shockwave.

“By introducing asymmetry into the explosion and adjusting the gas properties of the surrounding environment, we were able to reproduce a number of observed features from the real supernova such as the persistent one-sidedness in the radio images”, said Dr. Toby Potter.

So what’s going on? By creating a model which spans over a length of time, researchers were able to emulate an expanding shock front along the eastern edge of the supernova remnant. This region moves away more quickly than its counterpart and generates more radio emissions. When it encounters the equatorial ring – as observed by the Hubble Space Telescope – the effect becomes even more pronounced.

“Our simulation predicts that over time the faster shock will move beyond the ring first. When this happens, the lop-sidedness of radio asymmetry is expected to be reduced and may even swap sides.”

“The fact that the model matches the observations so well means that we now have a good handle on the physics of the expanding remnant and are beginning to understand the composition of the environment surrounding the supernova – which is a big piece of the puzzle solved in terms of how the remnant of SN1987A formed.”

Original Story Source: Astronomers dissect the aftermath of a Supernova – International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research News Release.