[/caption]

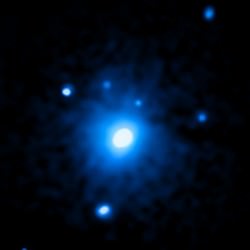

For the first time astronomers have located a pulsar – the super-dense, spinning remains of a star – nestled within the remnants of a supernova in the Small Magellanic Cloud. The image above, a composite of x-ray and optical light data acquired by NASA’s Chandra Observatory and ESA’s XMM-Newton, shows the pulsar shining brightly on the right surrounded by the ejected outer layers of its former stellar life.

The optically-bright area on the left is a large star-forming region of dust and gas nearby SXP 1062.

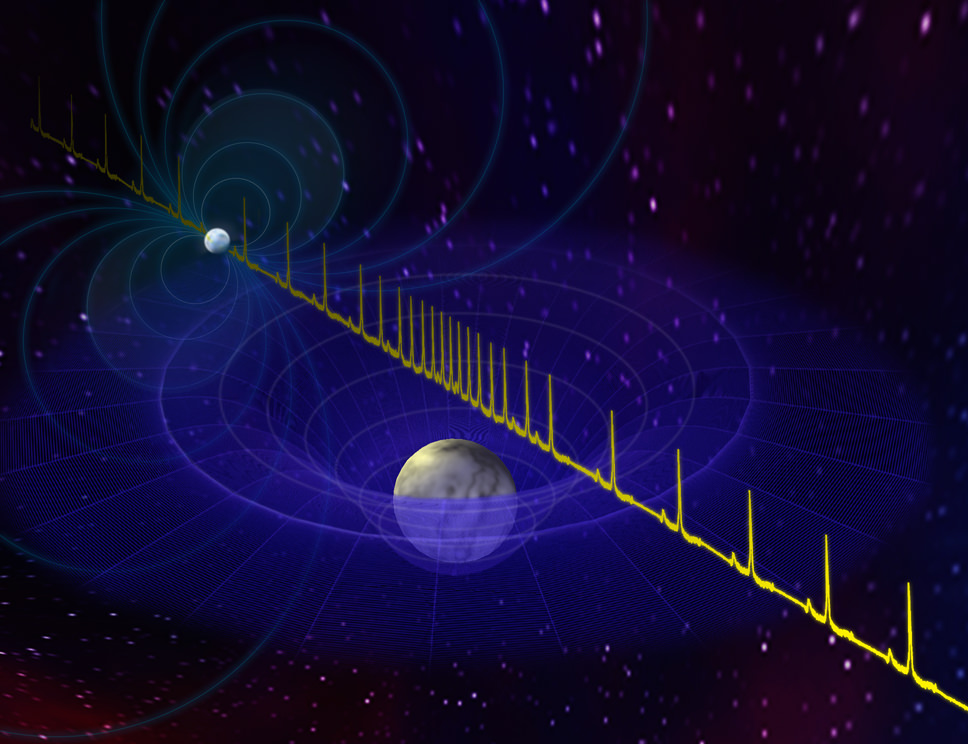

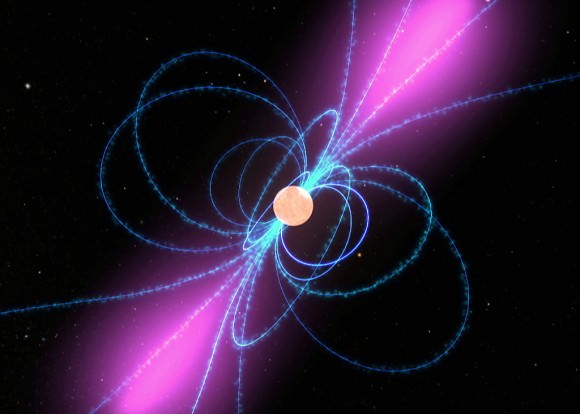

A pulsar is a neutron star that emits high-energy beams of radiation from its magnetic poles. These poles are not always aligned with its axis of rotation, and so the beams swing through space as the neutron star spins. If the Earth happens to be in direct line with the beams at some point along their path, we see them as rapidly flashing radiation sources… sort of like a cosmic lighthouse on overdrive.

What’s unusual about this pulsar – called SXP 1062 – is its slow rate of rotation. Its beams spin around at a rate of about once every 18 minutes, which is downright poky for a pulsar, most of which spin several times a second.

This makes SXP 1062 one of the slowest known pulsars discovered within the Small Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf galaxy cruising alongside our own Milky Way about 200,000 light-years distant.

The supernova that presumably created the pulsar and its surrounding remnant wrapping is estimated to have taken place between 10,000 and 40,000 years ago – relatively recently, by cosmic standards. To see a young pulsar spinning so slowly is extra unusual since younger pulsars have typically been observed to have rapid rotation rates. Understanding the cause of its leisurely pace will be the next goal for SXP 1062 researchers.

Read more about SXP 1062on the Chandra photo album page.

Image credit: X-ray & Optical: NASA/CXC/Univ.Potsdam/L.Oskinova et al.