Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! While you start your observing week out by watching the Mars Curiosity Landing, be sure to step outside and view the Aquarid meteor shower, too! It’s going to be a grand week for globular cluster studies and breezing along the Milky Way. Whenever you’re ready to learn some more history, mystery and just plain fun things about the night sky, then meet me in the back yard.

Monday, August 6 – Today in 2001 the Galileo spacecraft made its flyby of Jupiter’s moon – Io -sending back incredible images of the surface. For southern hemisphere observers, be on watch as the Iota Aquarid meteor shower peaks on this Universal date.

Tonight our studies of globular clusters continues as we look deeper into structure. As a rule, globular clusters normally contain a large number of variable stars, and most are usually the RR Lyrae type such as in earlier study M54. At one time they were known as “cluster variables,” with their number differing from one globular to another. Many globulars also contain vast numbers of white dwarfs. Some have neutron stars which are detected as pulsars, but out of all 151, only four have planetary nebulae in them.

Now, let us head toward the emerging constellation of Pegasus and the magnitude 6.5, class IV M15 (Right Ascension: 21 : 30.0 – Declination: +12 : 10). Easily located with even small binoculars about four degrees northwest of Enif, this magnificent globular cluster is a true delight in a telescope. Amongst the globulars, M15 ranks third in variable star population with 112 identified. As one of the densest of clusters, it is surprising that it is considered to be only class III. Its deeply concentrated core is easily apparent, and has begun the process of core collapse. The central core itself is very small compared to the cluster’s true size and almost half M15?s mass is contained within it. Although it has been studied by the Hubble, we still do not know if this density is caused by the cluster stars’ mutual gravity, or if it might disguise a supermassive object similar to those in galactic nuclei.

M15 was the first globular cluster in which a planetary nebula, known as Pease 1, could be identified. Larger aperture scopes can easily see it at high power. Surprisingly, M15 also is home to 9 known pulsars, which are neutron stars left behind from previous supernovae during the cluster’s evolution, and one of these is a double neutron star. While total resolution is impossible, a handful of bright stars can be picked out against that magnificent core region and wonderful chains and streams of members await your investigation tonight!

Tuesday, August 7 – On this date in 1959, Explorer 6 became the first satellite to transmit photographs of the Earth from its orbit.

Tonight, let’s return again to look at two giant globular clusters roughly equal in size, but not equal in class. To judge them fairly, you must use the same eyepiece. Start first by re-locating previous study M4. This is a class IX globular cluster. Notice the powder-like qualities. It might be heavily populated, but it is not dense. Now return to previous study M13. This is a class V globular cluster. Most telescopes will make out at least some resolution and a distinct core region. It is the level of condensation that determines the class. It is no different from judging magnitudes and simply takes practice.

Try your hand at M55 (Right Ascension:19 : 40.0 – Declination: -30 : 58) along the bottom of the Sagittarius “teapot” – it’s a class XI. Although it is a full magnitude brighter than class I M75, which we looked at earlier in the week, can you tell the difference in concentration? For those with GoTo systems, take a quick hop through Ophiuchus and look at the difference between NGC 6356 (class II) and NGC 6426 (class IX). If you want to try one that they can’t even classify? Look no further than M71 (Right Ascension: 19 : 53.8 – Declination: +18 : 47) in Sagitta. It’s all a wonderful game and the most fun comes from learning!

In the meantime, don’t forget all those other wonderful globular clusters such as 47 Tucanae, Omega Centauri, M56, M92, M28 and a host of others!

Wednesday, August 8 – Today in 2001, the Genesis Solar Particle Sample Return mission was launched. In September of 2004, it crash landed in the Utah desert with its precious payload. Although some of the specimens were contaminated, some did survive the mishap. So what is “star stuff?” Mostly highly charged particles generated from a star’s upper atmosphere and flowing out in a state of matter known as plasma…

Tonight let’s study one of the grandest of all solar winds as we seek out an area about three fingerwidths above the Sagittarius “teapot’s spout” as we have a look at magnificent M8 (Right Ascension: 18 : 03.8 – Declination: -24 : 23), the “Lagoon Nebula.”

Visible to the unaided eye as a hazy spot in the Milky Way, fantastic in binoculars, and an area truly worth study in any size scope, this 5200 light-year area of emission, reflection and dark nebulae has a rich history. Its involved star cluster – NGC 6530 – was first discovered by Flamsteed around 1680, and the nebula by Le Gentil in 1747. Cataloged by Lacaille as III.14 about 12 years before Messier listed it as number 8, its brightest region was recorded by John Herschel and the dark nebulae were discovered by Barnard.

Tremendous areas of starbirth are taking place in this region; while young, hot stars excite the gases in a are known as the “Hourglass,” around Herschel star 36 and 9 Sagittarius. Look closely around cluster NGC 6530 for Barnard dark nebulae B89 and B296 at the nebula’s southern edge. No matter how long you chose to swim in the “Lagoon” you will sure find more and more things to delight both the mind and the eye!

Thursday, August 9 – Today in 1976, the Luna 24 mission was launched on a return mission of its own – not to retrieve solar winds samples, but lunar soil! Remember this mission as we take a look at its landing site in the weeks ahead.

Tonight we’ll return to the nebula hunt as we head about a fingerwidth north and just slightly west of M8 for the “Trifid”…

M20 (Right Ascension: 18 : 02.3 – Declination: -23 : 02) was discovered by Messier on June 5, 1764, and much to his credit, he described it as a cluster of stars encased in nebulosity. This is truly a wonderful observation since the Trifid could not have been easy given his equipment. Some 20 years later William Herschel (although he usually avoided repeating Messier objects) found M20 of enough interest to assign separate designations to parts of this nebula – IV.41, V.10, V.11, V.12. The word “Trifid” was used to describe its beauty by John Herschel.

While M20 is a very tough call in binoculars, it is not impossible with good conditions to see the light of an area that left its home nearly a millennium ago. Even smaller scopes will pick up this round, hazy patch of both emission and reflection, but you will need aversion to see the dark nebula which divides it. This was cataloged by Barnard as B85. Larger telescopes will find the Trifid as one of the very few objects that actually appears much in the eyepiece as it does in photographs – with each lobe containing beautiful details, rifts and folds best seen at lower powers. Look for its cruciform star cluster and its fueling multiple system while you enjoy this triple treat tonight!

Friday, August 10 – Today in 1966 Lunar Orbiter 1 was successfully launched on its mission to survey the Moon. In the weeks ahead, we’ll take a look at what this mission sent back!

Tonight we’ll look at another star forming region as we head about a palm’s width north of the lid star (Lambda) in the Sagittarius teapot as we seek out “Omega”…

Easily viewed in binoculars of any size and outstanding in every telescope, the 5000 light-year distant Omega Nebula was first discovered by Philippe Loys de Cheseaux in 1745-46 and later (1764) cataloged by Messier as object 17. This beautiful emission nebula is the product of hot gases excited by the radiation of newly born stars. As part of a vast region of interstellar matter, many of its embedded stars don’t show in photographs, but reveal themselves beautifully to the eye of the telescope. As you look at its unique shape, you realize that many of these areas are obscured by dark dust, and this same dust is often illuminated by the stars themselves.

Often known as the “Swan,” M17 (Right Ascension: 18 : 20.8 – Declination: -16 : 11) will appear as a huge, glowing check mark or ghostly “2? in the sky – but power up if you use a larger telescope and look for a long, bright streak across its northern edge, with extensions to both the east and north. While the illuminating stars are truly hidden, you will see many glittering points in the structure itself and at least 35 of them are true members of this region spanning about 40 light-years that could contain up to 800 solar masses. It is awesome…

Saturday, August 11 – On this date in 1877, Asaph Hall of the U.S. Naval Observatory was very busy. This night would be the first time he would see Mars’ outer satellite Deimos! Six nights later, he observed Phobos, giving Mars its grand total of two moons.

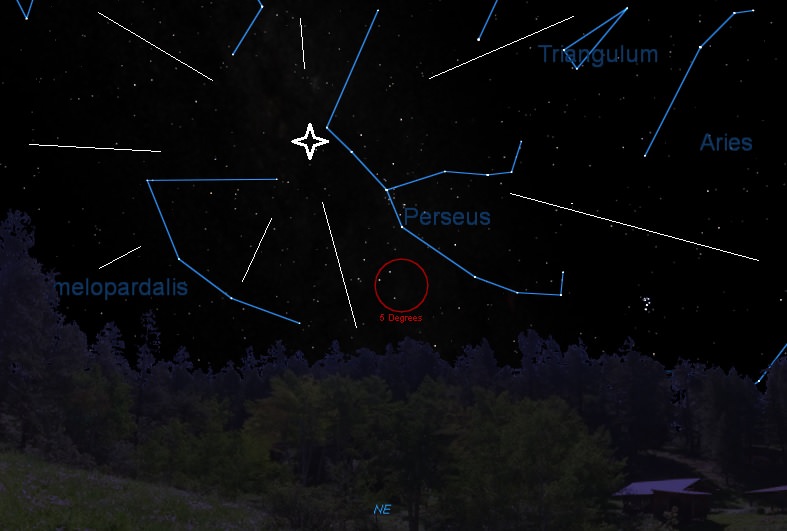

Tonight after midnight is the peak of the Perseid meteor shower, and this year there’s not so much Moon to contend with! Now let’s sit back and talk about the Perseids while we watch…

The Perseids are undoubtedly the most famous of all meteor showers and never fail to provide an impressive display. Their activity appears in Chinese history as far back as 36 AD. In 1839, Eduard Heis was the first observer to give an hourly count, and discovered their maximum rate was around 160 per hour at that time. He, and other observers, continued their studies in subsequent years to find that this number varied.

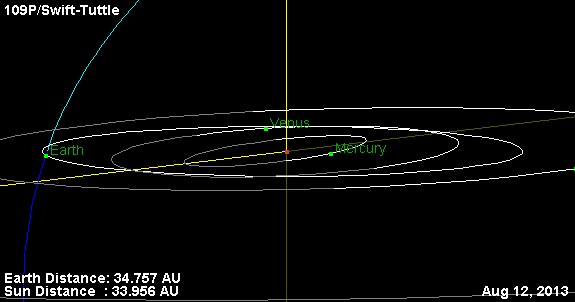

Giovanni Schiaparelli was the first to relate the orbit of the Perseids to periodic comet Swift-Tuttle (1862 III). The fall rates have both risen and fallen over the years as the Perseid stream was studied more deeply, and many complex variations were discovered. There are actually four individual streams derived from the comet’s 120 year orbital period which peak on slightly different nights, but tonight through tomorrow morning at dawn is our accepted peak.

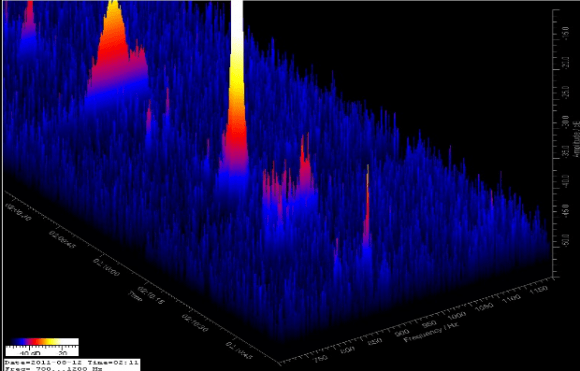

Meteors from this shower enter Earth’s atmosphere at a speed of 60 km/sec (134,000 miles per hour), from the general direction of the border between the constellations Perseus and Cassiopeia. While they can be seen anywhere in the sky, if you extend their paths backward, all the true members of the stream will point back to this region of the sky. For best success, position yourself so you are generally facing northeast and get comfortable. If you are clouded out, don’t worry. The Perseids will be around for a few more days yet, so continue to keep watch!

And speaking of watching… If you’re out late, be sure to watch for a Jupiter/Moon conjunction. What an inspiring bit of sky scenery to watch them rise together! For lucky viewers in the Indonesia area, this is an occultation event, so please be sure to check resources for times and locations in your area.

Sunday, August 12 – Did you mark your calendar to be up before dawn to view the Perseid meteor shower? Good!

Tonight while dark skies are on our side, we’ll fly with the “Eagle” as we hop another fingerwidth north of M17 and head for one of the most famous areas of starbirth – IC 4703.

While the open cluster NGC 6611 was first discovered by Cheseaux in 1745-6, it was Charles Messier who cataloged the object as M16 and he was the first to note the nebula IC 4703 (Right Ascension: 18 : 18.9 – Declination: -13 : 47), more commonly known as the “Eagle.” At 7000 light-years distant, this roughly 7th magnitude cluster and nebula can be spotted in binoculars, but at best it is a hint. As part of the same giant cloud of gas and dust as neighboring M17, the Eagle is also a place of starbirth illuminated by these hot, high energy stellar youngsters which are only about five and a half million years old.

In small to mid-sized telescopes, the cluster of around 20 brighter stars comes alive with a faint nebulosity that tends to be brighter in three areas. For larger telescopes, low power is essential. With good conditions, it is very possible to see areas of dark obscuration and the wonderful “notch” where the Pillars of Creation lie. Immortalized by the Hubble Space telescope, you won’t see them as grand or colorful as it did, but what a thrill to know they are there!

Until next week? Clear skies!