We’ve known for a while that complex chemistry occurs in space. Organic molecules have been detected in cold molecular clouds, and we have even found sugars and amino acids, the so-called “building blocks of life,” within several asteroids. The raw ingredients of terrestrial life are common in the Universe, and meteorites and comets may have even seeded Earth with those ingredients. This idea isn’t controversial. But there is a more radical idea that Earth was seeded not just with the building blocks of life but life itself. It’s known as panspermia, and a recent study has brought the idea back to popular science headlines. But the study is more subtle and interesting than some headlines suggest.

Continue reading “Asteroid Samples Returned to Earth Were Immediately Colonized by Bacteria”The Seven Most Intriguing Worlds to Search for Advanced Civilizations (So Far)

Sometimes, the easy calculations are the most interesting. A recent paper from Balázs Bradák of Kobe University in Japan is a case in point. In it, he takes an admittedly simplistic approach but comes up with seven known exoplanets that could hold the key to the biggest question of them all – are we alone?

Continue reading “The Seven Most Intriguing Worlds to Search for Advanced Civilizations (So Far)”Life Might Be Difficult to Find on a Single Planet But Obvious Across Many Worlds

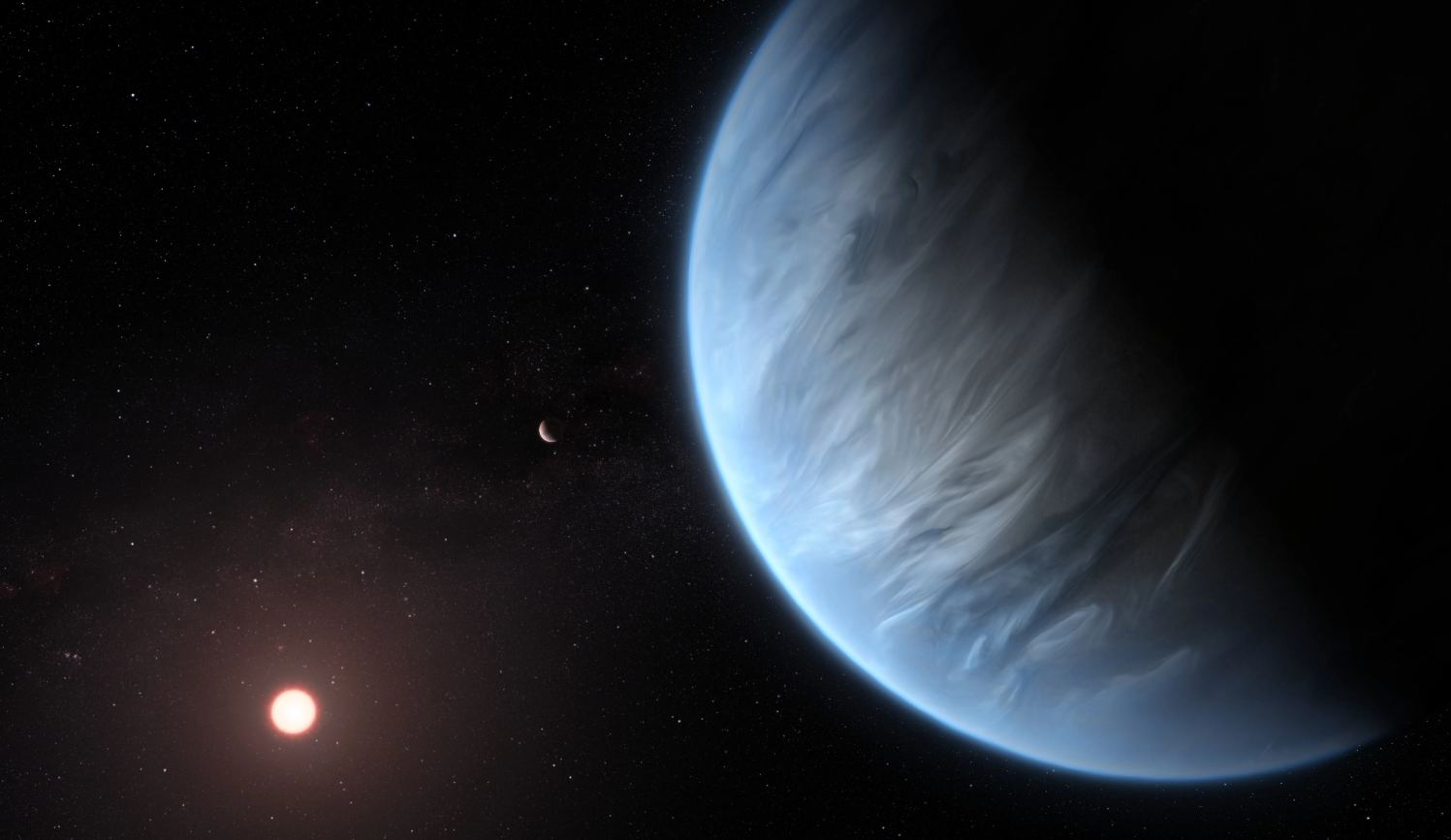

If we could detect a clear, unambiguous biosignature on just one of the thousands of exoplanets we know of, it would be a huge, game-changing moment for humanity. But it’s extremely difficult. We simply aren’t in a place where we can be certain that what we’re detecting means what we think or even hope it does.

But what if we looked at many potential worlds at once?

Continue reading “Life Might Be Difficult to Find on a Single Planet But Obvious Across Many Worlds”Cosmic Dust Could Spread Life from World to World Across the Galaxy

Does life appear independently on different planets in the galaxy? Or does it spread from world to world? Or does it do both?

New research shows how life could spread via a basic, simple pathway: cosmic dust.

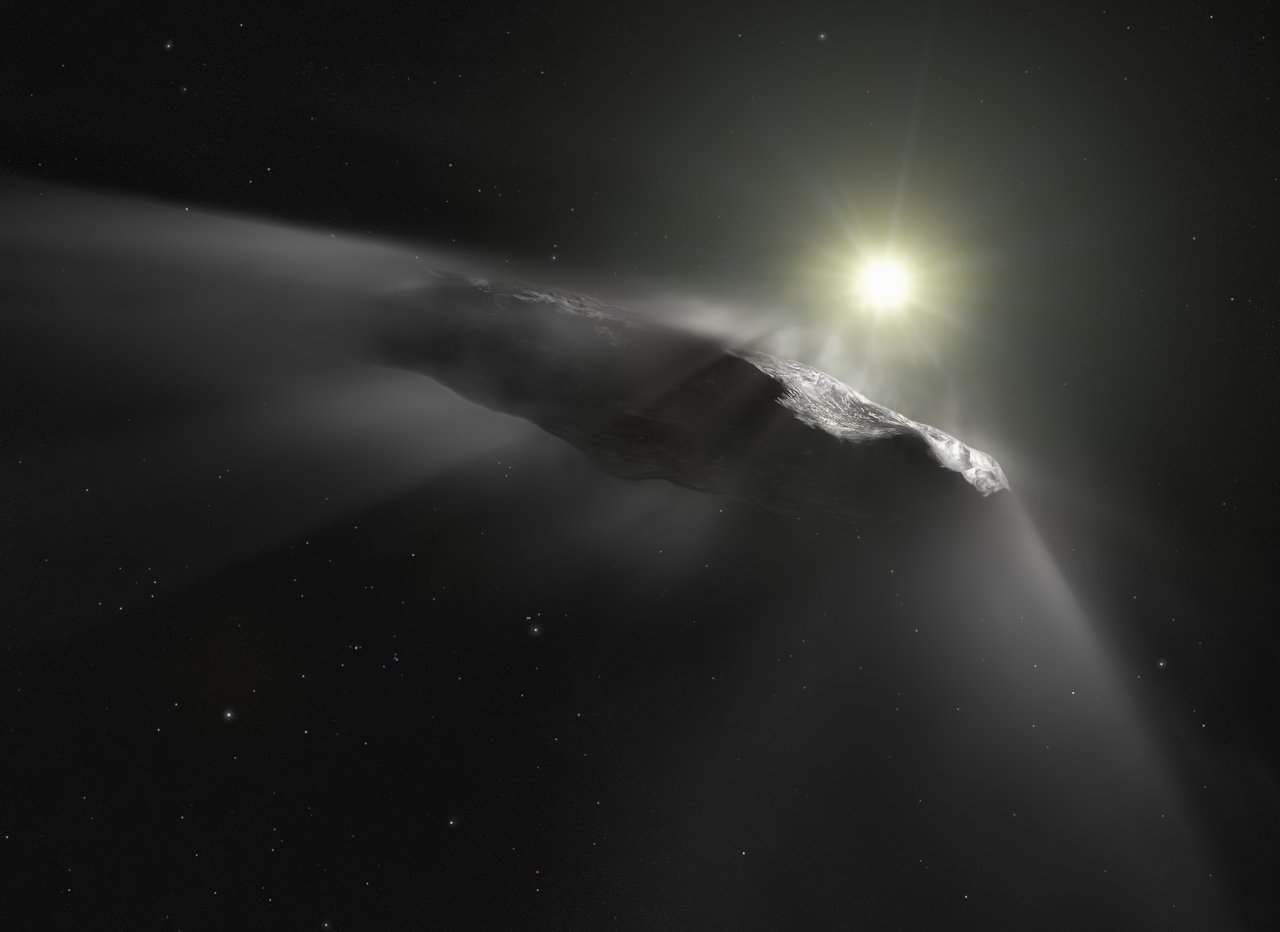

Continue reading “Cosmic Dust Could Spread Life from World to World Across the Galaxy”Since Interstellar Objects Crashed Into Earth in the Past, Could They Have Brought Life?

On October 19th, 2017, astronomers with the Pan-STARRS survey detected an interstellar object (ISO) passing through our Solar System for the first time. The object, known as 1I/2017 U1 Oumuamua, stimulated significant scientific debate and is still controversial today. One thing that all could agree on was that the detection of this object indicated that ISOs regularly enter our Solar System. What’s more, subsequent research has revealed that, on occasion, some of these objects come to Earth as meteorites and impact the surface.

This raises a very important question: if ISOs have been coming to Earth for billions of years, could it be that they brought the ingredients for life with them? In a recent paper, a team of researchers considered the implications of ISOs being responsible for panspermia – the theory that the seeds of life exist throughout the Universe and are distributed by asteroids, comets, and other celestial objects. According to their results, ISOs can potentially seed hundreds of thousands (or possibly billions) of Earth-like planets throughout the Milky Way.

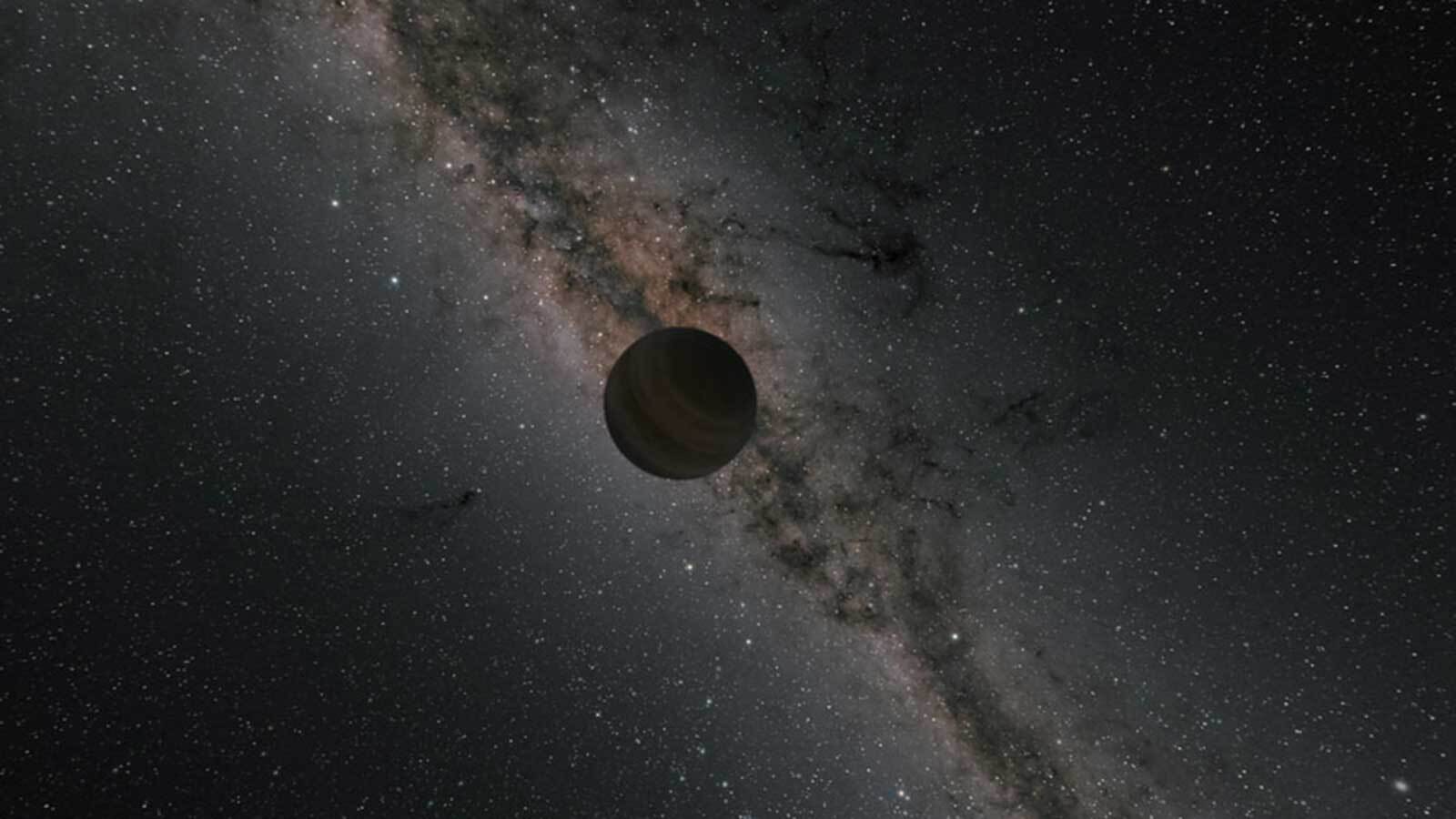

Continue reading “Since Interstellar Objects Crashed Into Earth in the Past, Could They Have Brought Life?”Rogue Planets Could be Habitable

The search for potentially habitable planets is focused on exoplanets—planets orbiting other stars—for good reason. The only planet we know of with life is Earth and sunlight fuels life here. But some estimates say there are many more rogue planets roaming through space, not bound to or warmed by any star.

Could some of them support life?

Continue reading “Rogue Planets Could be Habitable”Galactic Panspermia. How far Could Life Spread Naturally in a Galaxy Like the Milky Way?

Can life spread throughout a galaxy like the Milky Way without technological intervention? That question is largely unanswered. A new study is taking a swing at that question by using a simulated galaxy that’s similar to the Milky Way. Then they investigated that model to see how organic compounds might move between its star systems.

Continue reading “Galactic Panspermia. How far Could Life Spread Naturally in a Galaxy Like the Milky Way?”Earth’s toughest bacteria can survive unprotected in space for at least a year

A remarkable microbe named Deinococcus radiodurans (the name comes from the Greek deinos meaning terrible, kokkos meaning grain or berry, radius meaning radiation, and durare meaning surviving or withstanding) has survived a full year in the harsh environment of outer space aboard (but NOT inside) the International Space Station. This plucky prokaryote is affectionately known by fans as Conan the Bacterium, as seen in this classic 1990s NASA article.

The JAXA (Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency) ISS module Kib? has an unusual feature for spacecraft, a front porch! This exterior portion of the space station is fitted with robotic equipment to complete various experiments in outer space’s brutal conditions. One of these experiments was to expose cells of D. radiodurans for a year and then test the cells to see if they not only would survive but could reproduce effectively afterward. D. radiodurans proved to be up to the challenge, and what a challenge it was!

Continue reading “Earth’s toughest bacteria can survive unprotected in space for at least a year”Astronomers Finally Think They Understand Where Interstellar Object Oumuamua Came From and How it Formed

‘Oumuamua caused quite a stir when it visited our Solar System in 2017. It didn’t stay long, however, and when it was spotted with the Pan-STARRS telescope in Hawaii on October 19th, it was already leaving. But its appearance in our part of the Universe spawned a lot of conjecture on its nature and its origins.

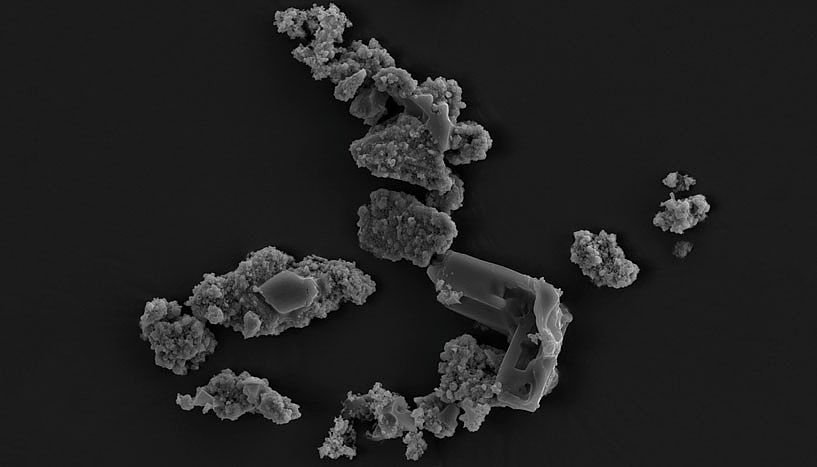

Continue reading “Astronomers Finally Think They Understand Where Interstellar Object Oumuamua Came From and How it Formed”A Microorganism With a Taste for Meteorites Could Help us Understand the Formation of Life on Earth

From the study of meteorite fragments that have fallen to Earth, scientists have confirmed that bacteria can not only survive the harsh conditions of space but can transport biological material between planets. Because of how common meteorite impacts were when life emerged on Earth (ca. 4 billion years ago), scientists have been pondering whether they may have delivered the necessary ingredients for life to thrive.

In a recent study, an international team led by astrobiologist Tetyana Milojevic from the University of Vienna examined a specific type of ancient bacteria that are known to thrive on extraterrestrial meteorites. By examining a meteorite that contained traces of this bacteria, the team determined that these bacteria prefer to feed on meteors – a find which could provide insight into how life emerged on Earth.

Continue reading “A Microorganism With a Taste for Meteorites Could Help us Understand the Formation of Life on Earth”