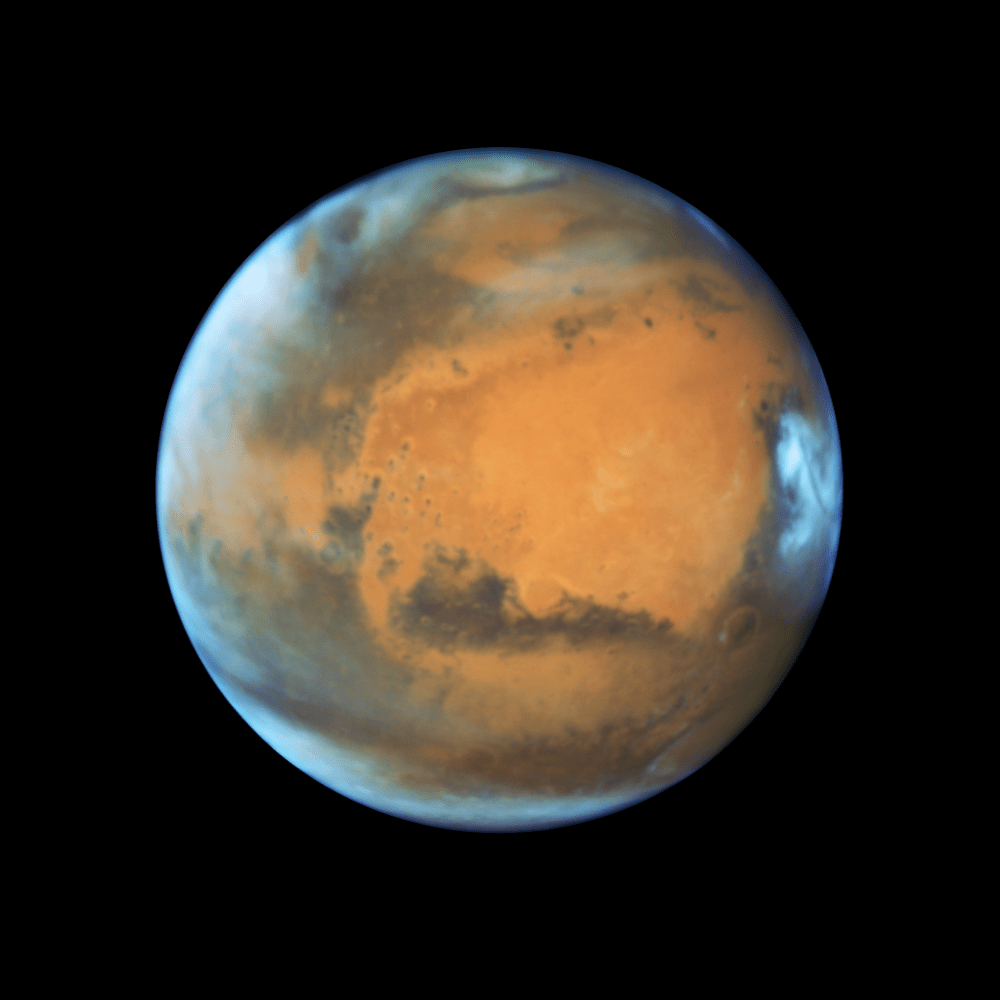

If you have a telescope, (What?! You don’t have one?) you’re in for a visual treat tonight. Mars will be at its closest point to Earth in 11 years on May 30. This event is worth checking out, whether with a telescope, astronomy binoculars, or online.

While today is when Mars is at its closest, you actually have a couple weeks to check this out, as the distance between Mars and Earth gradually becomes greater and greater. Today, Mars is 76 million kilometers (47.2 million miles) away, but up until June 12th it will still be no further than 77 million kilometers (48 million miles) away.

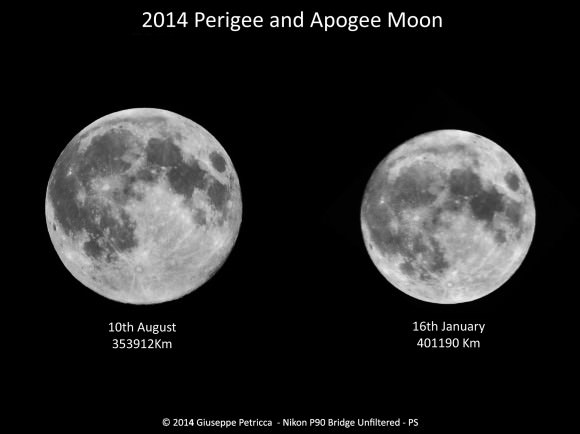

The furthest Mars can be from Earth is 401 million kilometers (249 million miles), when the two planets are on the opposite side of the Sun from each other.

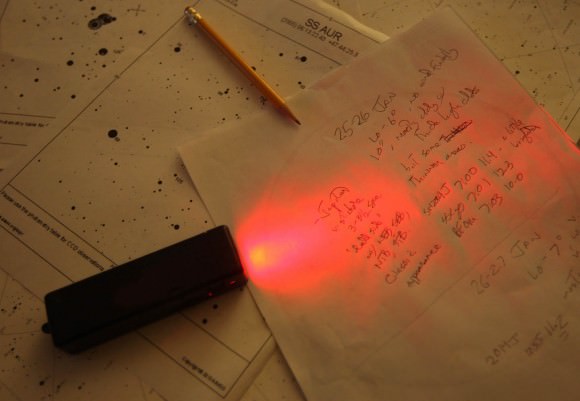

For most of us with backyard ‘scopes, it’s difficult to make out much detail. You can see Mars, and at the most you can make out a polar cap. But it’s still fascinating knowing you’re looking at another planet, one that was totally unknowable for most humans who preceded us. A planet that we have rovers on, and that we have several craft in orbit around.

If you don’t have a scope, have no fear. There will be a flood of great astro-photos of Mars in the next few days. There are also options for live streaming feeds from powerful Earth-based telescopes.

The last time Mars was this close to Earth was 2005. A couple years before, the distance shrank to 55.7 million km (34.6 million miles.) That was the closest Mars and Earth have been in several thousand years. In 2018, the two planets will be nearly that close again.

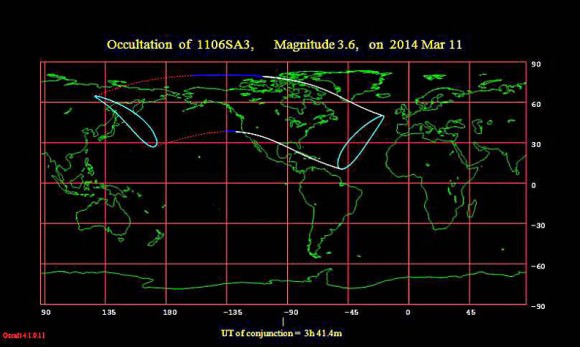

This event is often called “opposition”, but it’s actually more correctly called “closest approach.” Opposition occurs a couple weeks before closest approach, when Mars is directly opposite the Sun.

But whether you call it opposition, or closest approach, the event itself is significant for more than just looking at it. Missions to Mars are planned when the two planets are close to each other. This reduces mission times drastically.

Mars Express, the mission being conducted by the European Space Agency (ESA) was launched in 2003, when the two planets were as close to each other as they’ve been in thousands of years. All missions to Mars can’t be so lucky, but they all strive to take advantage of the orbital cycles of the two planets, by nailing launch dates that work in our favour.

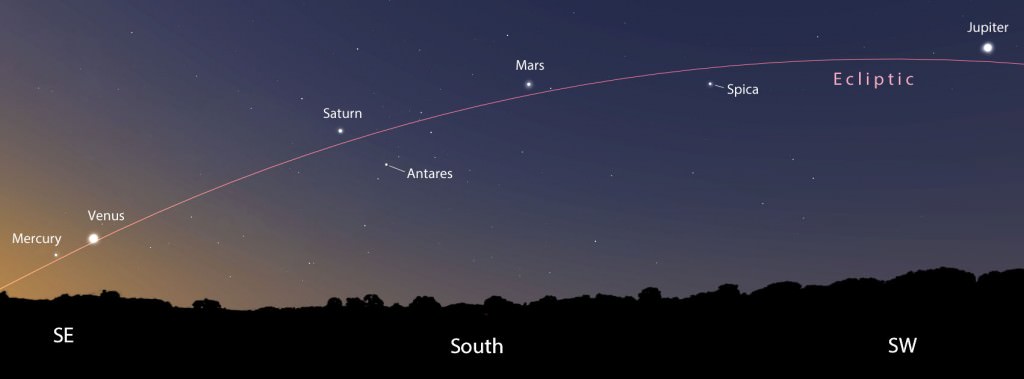

As for finding Mars in the night sky, it’s not that difficult. If you have clear skies where you are, Mars will appear as a bright, fire-yellow star.

“Just look southeast after the end of twilight, and you can’t miss it,” says Alan MacRobert, a senior editor of Sky & Telescope magazine, in a statement. “Mars looks almost scary now, compared to how it normally looks in the sky.”

Although Mars is the closest thing in the sky to Earth right now, other than the Moon, it isn’t the brightest thing in the night sky. That honour is reserved for Jupiter, even though it’s ten times further away. Jupiter is twenty times larger in diameter than Mars, so it reflects much more sunlight and appears much brighter. (Obviously, everything in the night sky pales in comparison to the Moon.)

The reason for such a variation in distances between the planets lies in their elliptical orbits around the Sun. There’s a great video showing how their orbits change the distance between the two planets, here.

If you don’t have a telescope, you can still check Mars out. Go to slooh.com to check out live feeds from a proper telescope.