Several nights ago the chill of interstellar space refrigerated the countryside as temperatures fell well below zero. That didn’t discourage the likes of Orion and his seasonal friends Gemini, Perseus and Auriga. They only seemed to grow brighter as the air grew sharper.

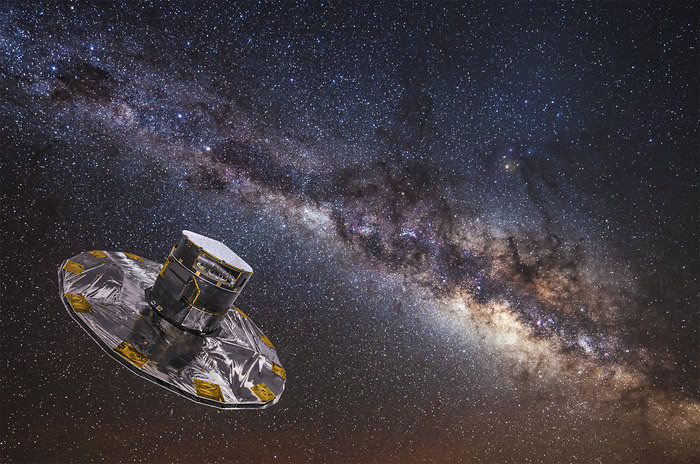

Wending between these familiar constellations like a river steaming in the cold was the Milky Way. The name has always been slightly confusing as it refers to both the milky band of starlight and the galaxy itself. Every single star you see at night belongs to our galaxy, a 100,000 light-year-wide flattened disk scintillating with over 400 billion suns.

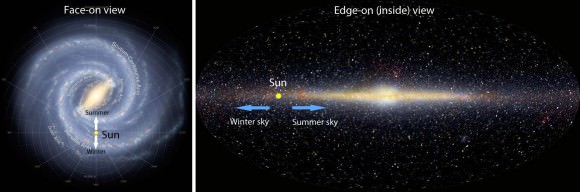

Earth, Sun and planets huddle together within the mid-plane of the disk, so that when we look straight into it, the density of stars piles up over thousands of light years to form a thick band across the sky. Since most of the stars are very distant and therefore faint, they can’t be seen individually with the naked eye. They blend together to give the Milky Way a milky or hazy look.

In a snowstorm, we easily distinguish individual snowflakes falling in front of our face, but looking into the distance, the flakes blend together to create a white, foggy haze. Replace the snowflakes with stars and you have the Milky Way – with a caveat. If we lived in the center of our galaxy, the sky would be milky with stars in all directions just like that snowstorm, but since the Sun occupies the flat plane, they only appear thick when our line of sight is aimed along the galaxy’s equator. Look above and below the disk and the stars quickly thin out as our gaze pierces through the galaxy’s plane and into intergalactic space.

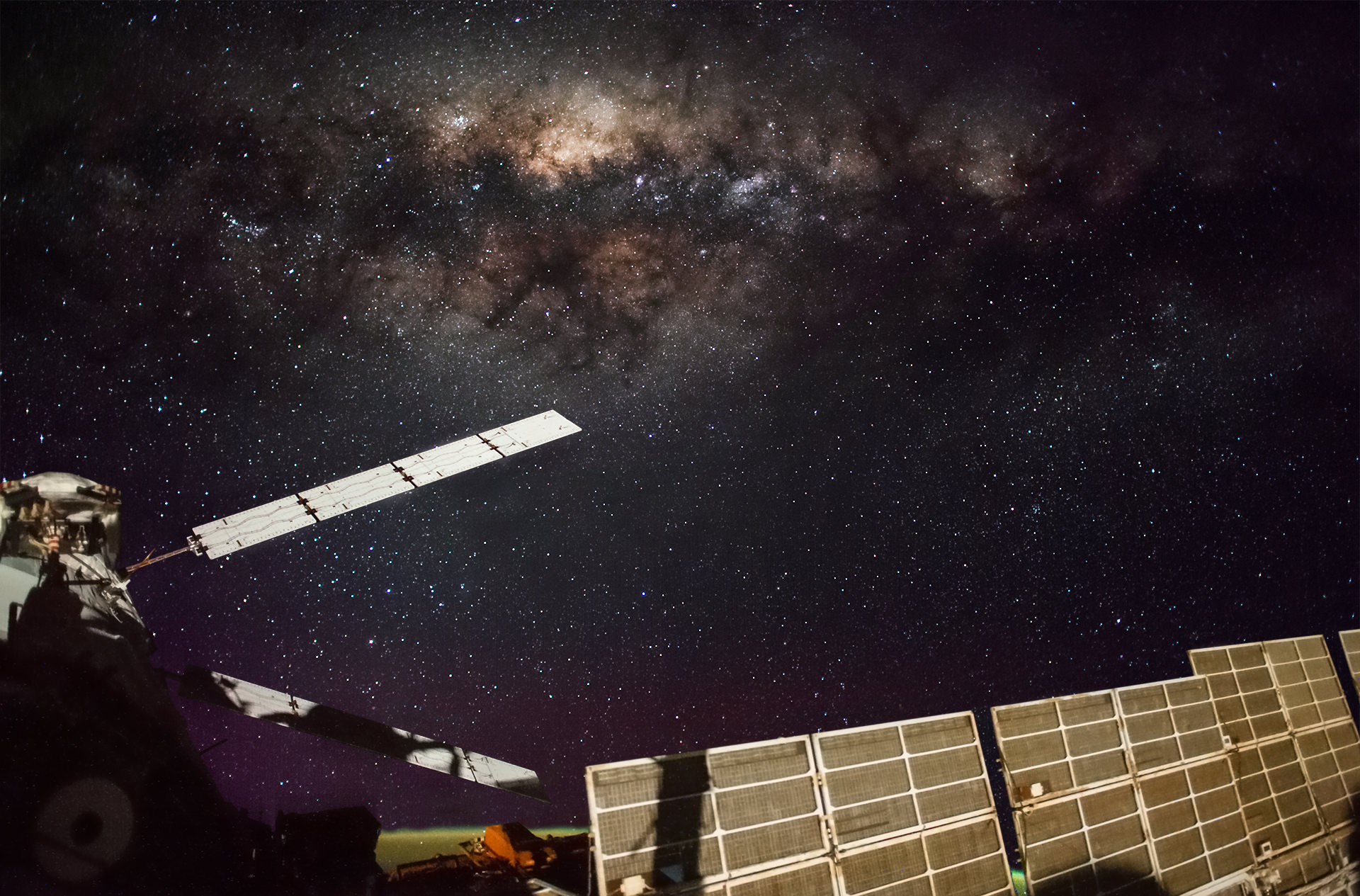

If you could float in space some distance from the brilliant ball of Earth, you’d see that the Milky Way band passes above, around and below you like a giant hula-hoop. Back on the ground, we can only see about two-thirds of the band over the course of a year. The other third is below the horizon and visible only from the opposite hemisphere, providing yet another good reason to make that trip to Tahiti or Ayers Rock in Australia.

Few know the winter version of the Milky Way that stands above the southeastern horizon around 10:30-11 p.m. local time on moonless nights in early December. No surprise, given it hardly compares to the brightness of the summertime version. This has much to do with where the Sun is located inside the galaxy, some 30,000 light years away from the center or more than halfway to the edge.

On late fall and winter nights, our planet faces the galaxy’s outer suburbs and countryside where the stars thin out until giving way to relatively starless intergalactic space. Indeed, the anticenter of the Milky Way lies not far from the star El Nath (Beta Tauri) where Taurus meets Auriga. While the hazy band of the Milky Way is still visible through Auriga and Taurus, it’s thin and anemic compared to summer’s billowy star clouds.

At nightfall in July and August, we face toward the galaxy’s center where 30,000 light years worth of stars, star clouds and nebulae stack up to fatten the Milky Way into a bright, chunky arch on summer evenings compared to winter’s thin gruel.

The winter Milky Way starts east of brilliant Sirius and grazes the east side of Orion before ascending into Gemini and Auriga and arching over into the western sky to Cassiopeia’s “W”. Binoculars and telescopes resolve it into individual stars and star clusters and help us appreciate what a truly beautiful and rich place our galactic home is.

Few sights that impress us with the scope and scale of where we live than seeing the Milky Way under a dark sky during the silence of a winter night. Picture Earth and yourself as members of that glowing carpet of stars, and when you can’t take the cold anymore, enjoy the delicious pleasure of stepping inside to unwrap and warm up. You’ve been on a long journey.