When the Opportunity rover landed on Mars on January 25th, 2004, its mission was only meant to last for about 90 Earth days. But the little rover that could has exceeded all expectations by remaining in operation (as of the writing of this article) for a total of 13 years and 231 days and traveled a total of about 50 km (28 mi). Basically, Opportunity has continued to remain mobile and gather scientific data 50 times longer than its designated lifespan.

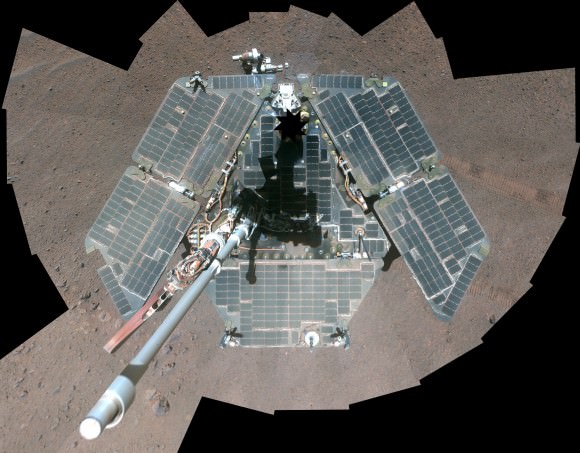

And according to a recent announcement from NASA’s Mars Exploration Program (MEP), the rover managed to survive yet another winter on Mars. Having endured the its eight Martian winter in a row, and with its solar panels in encouragingly clean condition, the rover will be in good shape for the coming dust-storm season. It also means the rover will live to see its 14th anniversary, which will take place on January 25th, 2018.

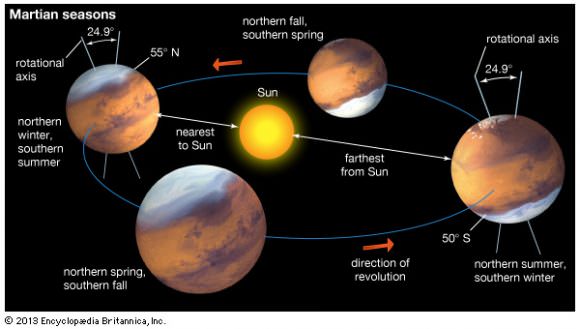

On Mars, a single year lasts the equivalent of 686.971 Earth days (or 1.88 Earth years). And since Mars’ axis is inclined 25.19° to its orbital plane (compared to Earth’s axial tilt of just over 23°), Mars also experiences seasons. However, these tend to last about twice as long as the seasons on Earth. And of course, the seasons on Mars’ are also much colder, with temperatures averaging about -63 °C (-82°F).

As Jennifer Herman, the power subsystem operations team lead for Opportunity at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, recalled in a NASA MEP press statement:

“I didn’t start working on this project until about Sol 300, and I was told not to get too settled in because Spirit and Opportunity probably wouldn’t make it through that first Martian winter. Now, Opportunity has made it through the worst part of its eighth Martian winter.”

At present, both the Opportunity and Spirit rover are in Mars’ southern hemisphere. Here, the Sun appears in the northern sky during the fall and winter, so the rovers need to tilt their solar-arrays northward. Back in 2004, the Spirit rover had lost the use of two of its wheels, and could therefore not maneuver out of a sand trap it had become stuck in. As such, it was unable to tilt itself northward and did not survive its fourth Martian winter (in 2009).

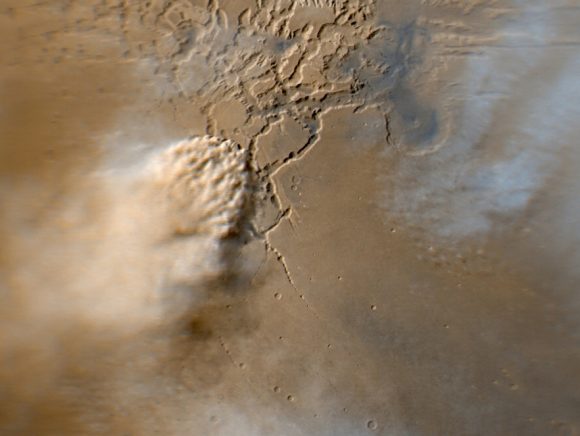

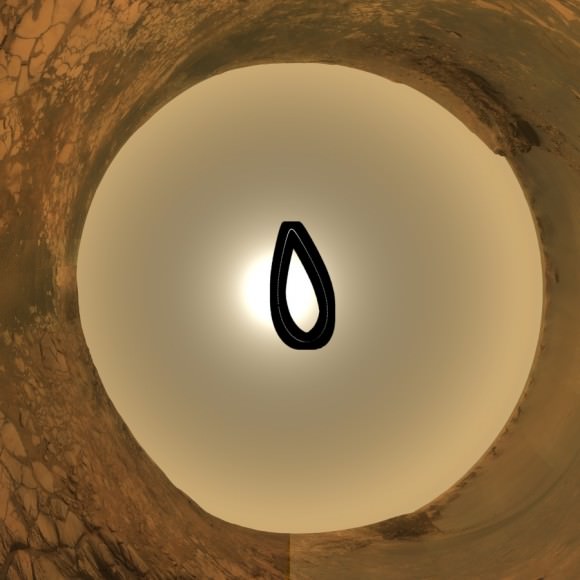

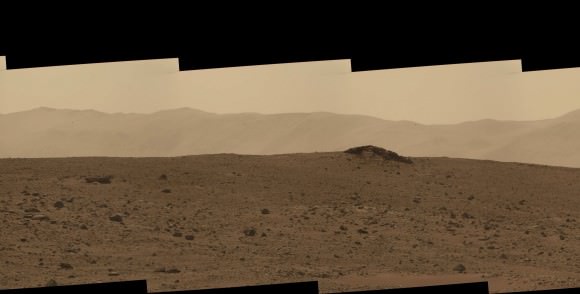

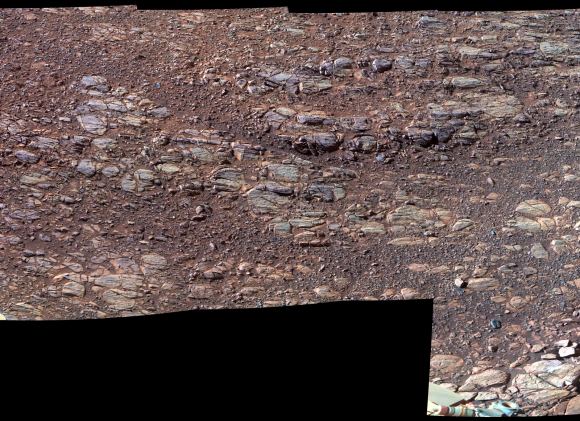

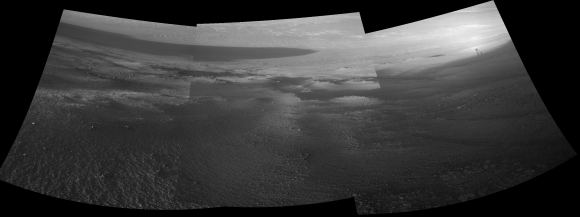

However, Opportunity’s current position – Perseverance Valley, a fluid-carved region on the inner slope at the edge of the Endeavour Crater – meant that it was well-positioned to keep working through late fall and early winter this year. This was ensured by the stops the rover made at energy-favorable locations, where it would inspect local rocks, examine the valley’s shape and image the surrounding area, all the while absorbing ample energy from the Sun.

Five months ago, the rover entered the top of the valley, which runs eastward down the inner slope of the Endurance Crater’s western rim. Since that time, Opportunity has been conducting stops between drives at north-facing sites, which are situated along the southern edge of the channel. The rover team calls the sites “lily pads”, since these places are spots that the rover need to hop across during its mission.

This is necessary, given that Opportunity does not rely on a radioisotope thermoelectric generator like Curiosity does. While winter conditions affect the use of electrical heaters and batteries on both rovers, Opportunity is different in that it’s activities are more subject to seasonal change. Whereas Curiosity will simply allocate less energy to performing tasks in the winter, Opportunity needs to pick its routes to ensure it stays powered up.

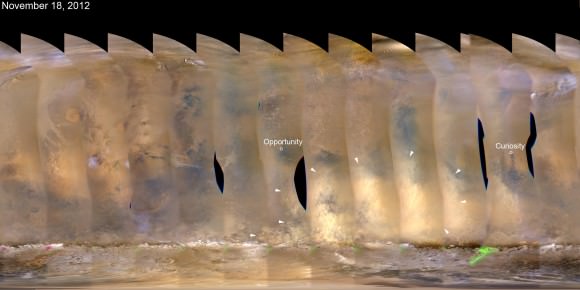

During some of its previous winters, the Opportunity rover was not as well-situated as it currently is. During its fifth winter (2011-2012) the rover spent 19 weeks at one spot because no other places that allowed for a northward-facing tilt were available within driving distance. On the other hand, its first winter (2004-2005) was spent in the southern half of the Endurance Crater, where all grounds are favorable since they face north.

As the person who is chiefly responsible for advising other mission scientists on how much energy Opportunity has available on each Martian day (sol) for conducting activities like driving and observing – a task she performs for Curiosity as well – Herman understand the relationship between power usage and the seasons all too well. “Relying on solar energy for Opportunity keeps us constantly aware of the season on Mars and the terrain that the rover is on, more than for Curiosity,” she said.

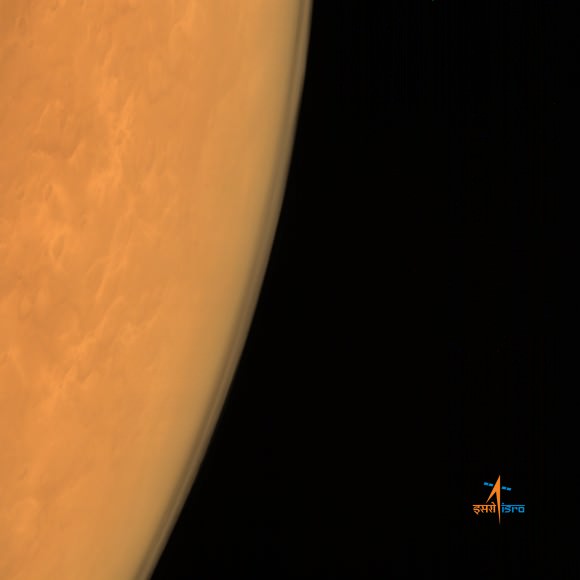

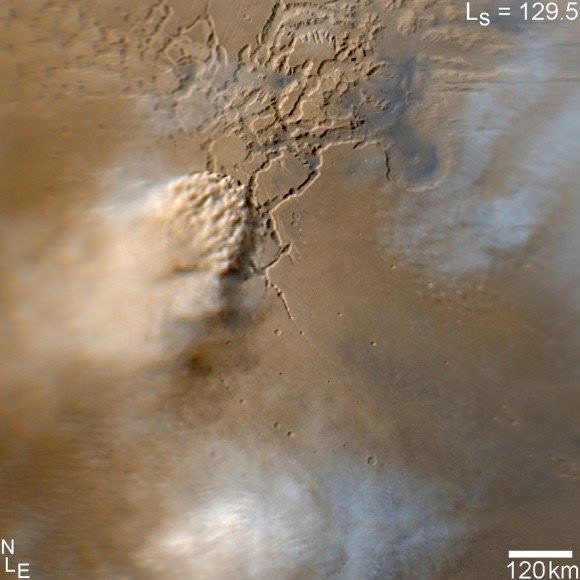

Another factor which can influence Opportunity‘s power supply is how much dust is in the sky and how much of it gets onto the rover’s solar arrays. This is highly-dependent on prevailing wind conditions, which can both stir up dust storms and clear away dust deposits on the rover – basically, they are a real mixed blessing! During autumn and winter in the southern-hemisphere, the skies are generally clear where Opportunity operates.

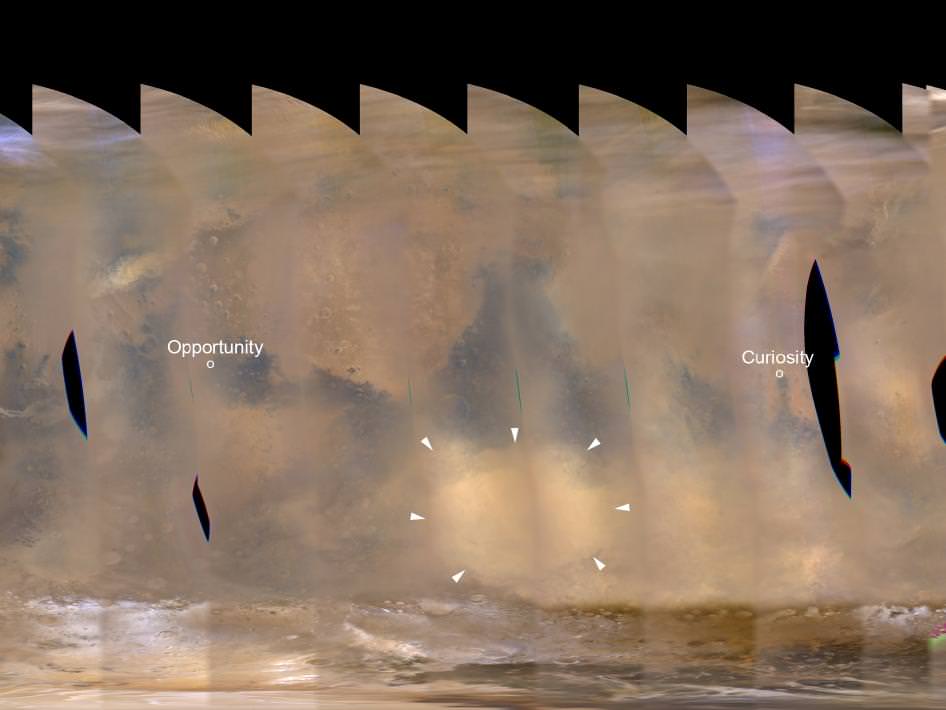

Spring and summer is when the storms are most common in Mars’ southern hemisphere, though they don’t happen every year. The latest example took place in 2007, which led to a severe reduction in the amount of sunlight (and hence, solar energy) Spirit and Opportunity were able to receive. This required both rovers to enact emergency protocols and reduce the amount of operations and communications they conducted.

The amount of dust on the rover’s solar arrays going into autumn can also vary from year to year. This year, the array was dustier than in all but one of the previous Martian autumns it experienced. Luckily, as Herman explained, things worked out for the rover:

“We were worried that the dust accumulation this winter would be similar to some of the worst winters we’ve had, and that we might come out of the winter with a very dusty array, but we’ve had some recent dust cleaning that was nice to see. Now I’m more optimistic. If Opportunity’s solar arrays keep getting cleaned as they have recently, she’ll be in a good position to survive a major dust storm. It’s been more than 10 Earth years since the last one and we need to be vigilant.”

In the coming months, the Opportunity team hopes to investigate how the Perseverance Valley was cut into the rim of the Endeavor crater. As Matt Golombek, an Opportunity Project Scientist at JPL, related:

“We have not been seeing anything screamingly diagnostic, in the valley itself, about how much water was involved in the flow. We may get good diagnostic clues from the deposits at the bottom of the valley, but we don’t want to be there yet, because that’s level ground with no more lily pads.”

With its eighth winter finished and Opportunity still in good working order, we can expect the tenacious rover to keep turning up interesting finds on Mars. These include clues about Mars’ warmer, wetter past, which likely included a standing body of water in the Endeavor crater. And assuming conditions are favorable in the coming year, we can expect that Opportunity will continue to push the boundaries of both science and its own endurance!

Further Reading: NASA