[/caption]

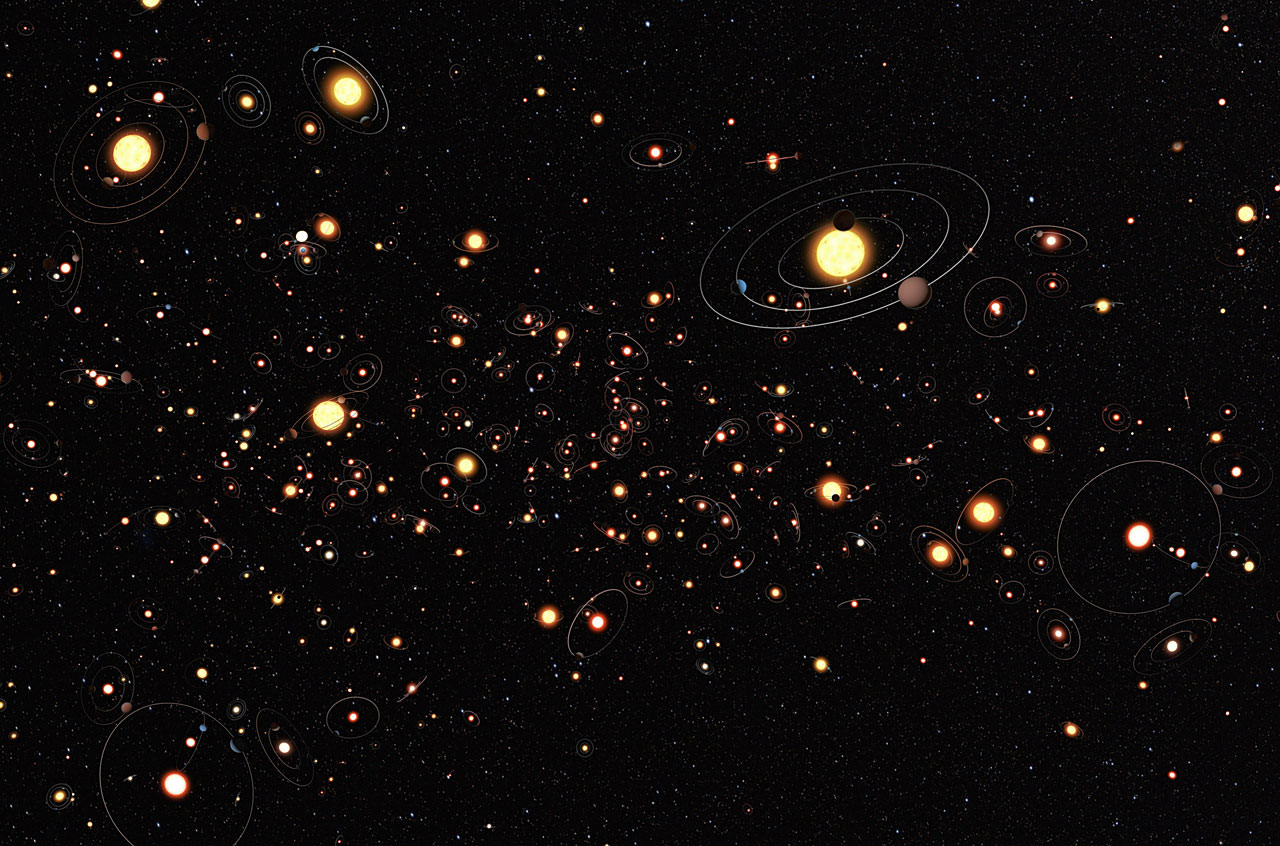

How common are planets in the Milky Way? A new study using gravitational microlensing suggests that every star in our night sky has at least one planet circling it. “We used to think that the Earth might be unique in our galaxy,” said Daniel Kubas, a co-lead author of a paper that appears this week in the journal Nature. “But now it seems that there are literally billions of planets with masses similar to Earth orbiting stars in the Milky Way.”

Over the past 16 years, astronomers have detected more than 3,035 exoplanets – 2,326 candidates and 709 confirmed planets orbiting other stars. Most of these extrasolar planets have been discovered using the radial velocity method (detecting the effect of the gravitational pull of the planet on its host star) or the transit method (catching the planet as it passes in front of its star, slightly dimming it.) Those two methods usually tend to find large planets that are relatively close to their parent star.

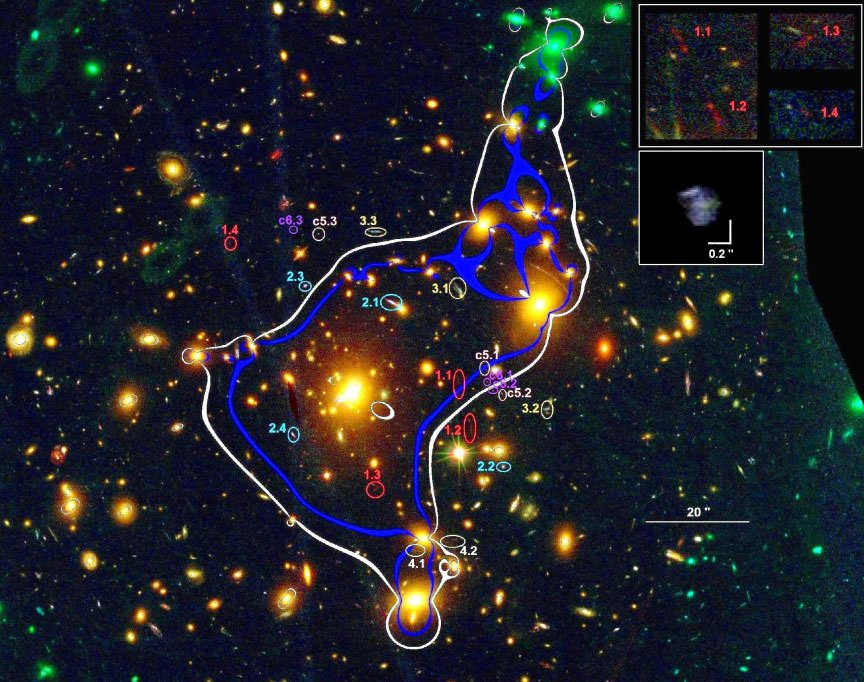

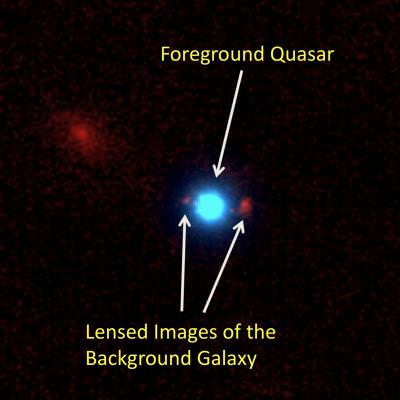

But another method, gravitational microlensing — where the light from the background star is amplified by the gravity of the foreground star, which then acts as a magnifying glass — is able to find planets over a wide range of mass that are further away from their stars.

An international team of astronomers used the technique of gravitational microlensing in six-year search that surveyed millions of stars. “We conclude that stars are orbited by planets as a rule, rather than the exception,” the team wrote in their paper.

“We have searched for evidence for exoplanets in six years of microlensing observations,” said lead author Arnaud Cassan from the Institut de Astrophysique in Paris. “Remarkably, these data show that planets are more common than stars in our galaxy. We also found that lighter planets, such as super-Earths or cool Neptunes, must be more common than heavier ones.”

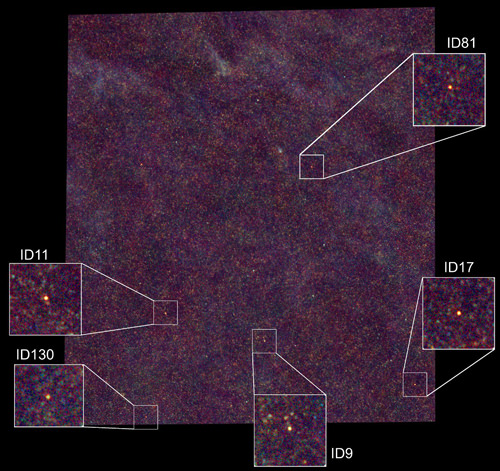

The astronomers surveyed millions of stars looking for microlensing events, and 3,247 such events in 2002-2007 were spotted in data from the European Southern Observatory’s PLANET and OGLE searches. The precise alignment needed for microlensing is very unlikely, and statistical results were inferred from detections and non-detections on a representative subset of 440 light curves.

Three exoplanets were actually detected: a super-Earth and planets with masses comparable to Neptune and Jupiter. The team said that by microlensing standards, this is an impressive haul, and that in detecting three planets, they were either incredibly lucky despite huge odds against them, or planets are so abundant in the Milky Way that it was almost inevitable.

The astronomers then combined information about the three positive exoplanet detections with seven additional detections from earlier work, as well as the huge numbers of non-detections in the six years’ worth of data (non-detections are just as important for the statistical analysis and are much more numerous, the team said.) The conclusion was that one in six of the stars studied hosts a planet of similar mass to Jupiter, half have Neptune-mass planets and two thirds have super-Earths.

This works out to about 100 billion exoplanets in our galaxy.

The survey was sensitive to planets between 75 million kilometers and 1.5 billion kilometers from their stars (in the Solar System this range would include all the planets from Venus to Saturn) and with masses ranging from five times the Earth up to ten times Jupiter.

This also shows that microlensing is a viable way to find exoplanets. Astronomers hope to use other methods in the future to find even more planets.

“I have a list of 17 different ways to find exoplanets and only five have been used so far,” said Virginia Trimble from the University of California, Irvine and the Las Cumbres Observatory, providing commentary at the American Astronomical Scoeity meeting this week, “I expect we’ll be finding many more planets in the future.”