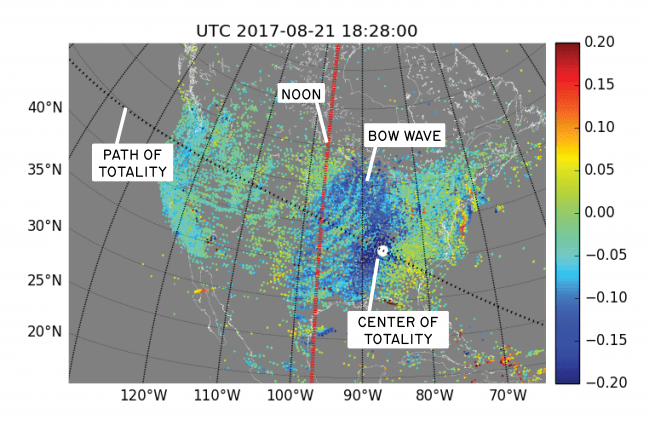

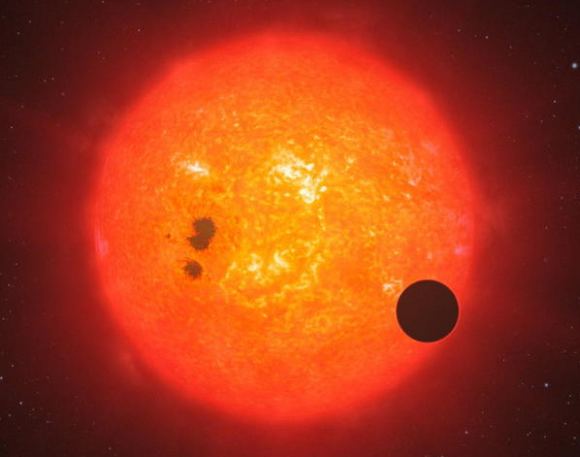

It’s long been predicted that a solar eclipse would cause a bow wave in Earth’s ionosphere. The August 2017 eclipse—called the “Great American Eclipse” because it crossed the continental US— gave scientists a chance to test that prediction. Scientists at MIT’s Haystack Observatory used more than 2,000 GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) receivers across the continental US to observe this type of bow wave for the first time.

The Great American Eclipse took 90 minutes to cross the US, with totality lasting only a few minutes at any location. As the Moon’s shadow moved across the US at supersonic speeds, it created a rapid temperature drop. After moving on, the temperature rose again. This rapid heating and cooling is what caused the ionospheric bow wave.

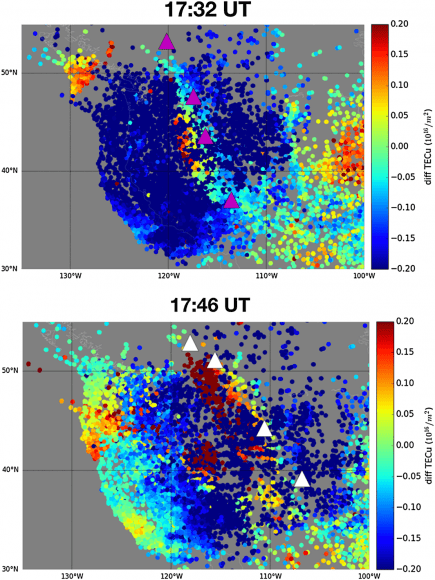

The bow wave itself is made up of fluctuations in the electron content of the ionosphere. The GNSS receivers collect very accurate data on the TEC (Total Electron Content) of the ionosphere. This animation shows the bow wave of electron content moving across the US.

The details of this bow wave were published in a paper by Shun-Rong Zhang and colleagues at MIT’s Haystack Observatory, and colleagues at the University of Tromso in Norway. In their paper, they explain it like this: “The eclipse shadow has a supersonic motion which [generates] atmospheric bow waves, similar to a fast-moving river boat, with waves starting in the lower atmosphere and propagating into the ionosphere. Eclipse passage generated clear ionospheric bow waves in electron content disturbances emanating from totality primarily over central/eastern United States. Study of wave characteristics reveals complex interconnections between the sun, moon, and Earth’s neutral atmosphere and ionosphere.”

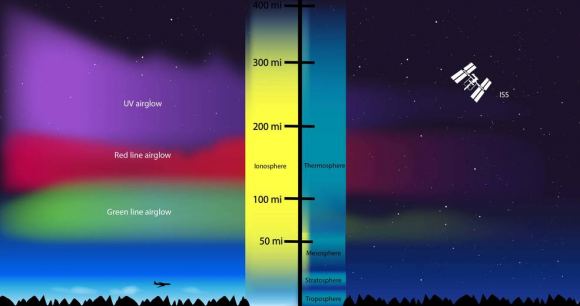

The ionosphere stretches from about 50 km to 1000 km in altitude during the day. It swells as radiation from the Sun reaches Earth, and subsides at night. Its size is always fluctuating during the day. It’s called the ionosphere because it’s the region where charged particles created by solar radiation reside. The ionosphere is also where auroras occur. But more importantly, it’s where radio waves propagate.

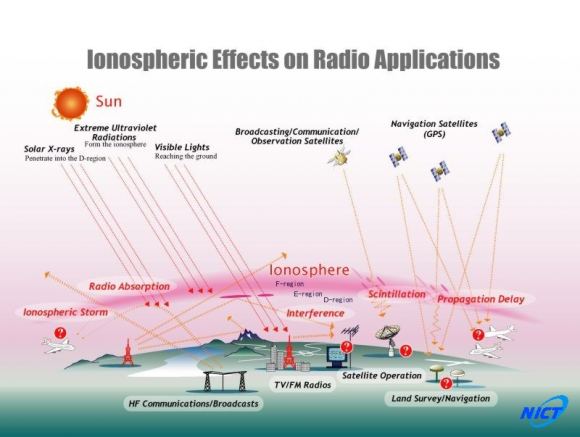

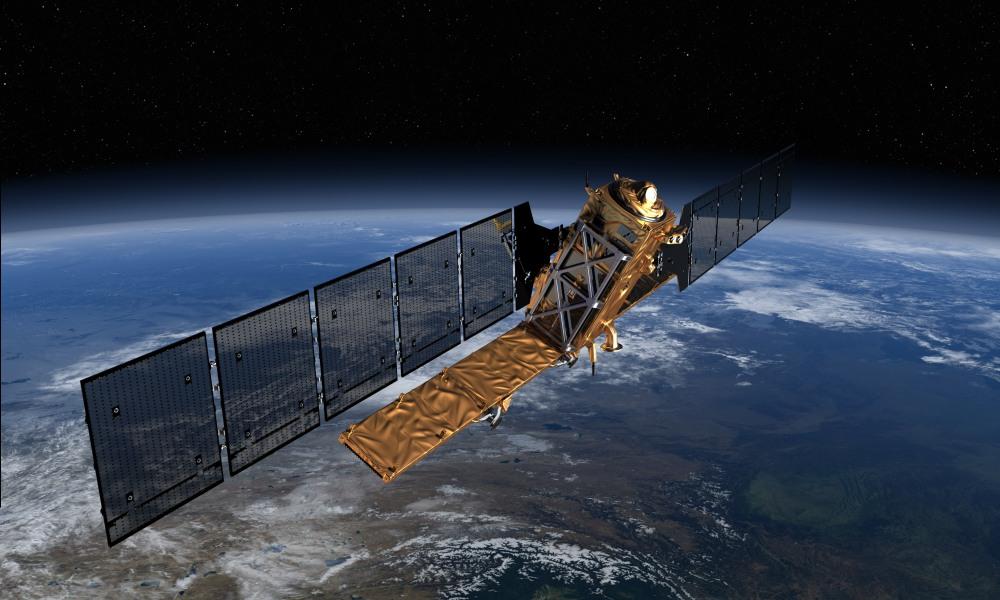

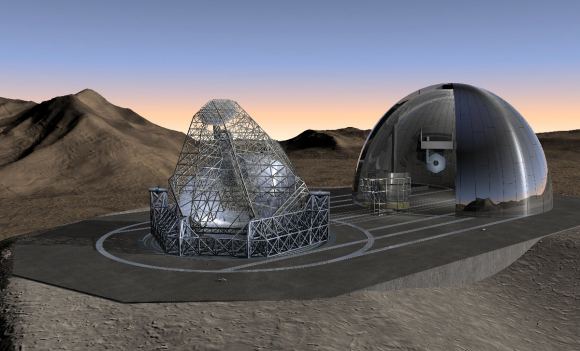

The ionosphere plays an important role in the modern world. It allows radio waves to travel over the horizon, and also affects satellite communications. This image shows some of the complex ways our communications systems interact with the ionosphere.

There’s a lot going on in the ionosphere. There are different types of waves and disturbances besides the bow wave. A better understanding of the ionosphere is important in our modern world, and the August eclipse gave scientists a chance not only to observe the bow wave, but also to study the ionosphere in greater detail.

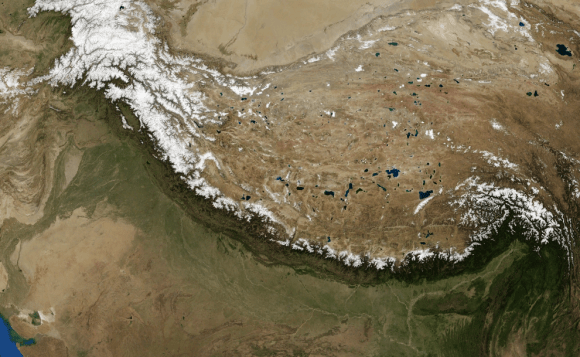

The GNSS data used to observe the bow wave was key in another study as well. This one was also published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, and was led by Anthea Coster of the Haystack Observatory. The data from the network of GNSS was used to detect the Total Electron Content (TEC) and the differential TEC. They then analyzed that data for a couple things during the passage of the eclipse: the latitudinal and longitudinal response of the TEC, and the presence of any Travelling Ionospheric Disturbances (TID) to the TEC.

Predictions showed a 35% reduction in TEC, but the team was surprised to find a reduction of up to 60%. They were also surprised to find structures of increased TEC over the Rocky Mountains, though that was never predicted. These structures are probably linked to atmospheric waves created in the lower atmosphere by the Rocky Mountains during the solar eclipse, but their exact nature needs to be investigated.

“… a giant active celestial experiment provided by the sun and moon.” – Phil Erickson, assistant director at Haystack Observatory.

“Since the first days of radio communications more than 100 years ago, eclipses have been known to have large and sometimes unanticipated effects on the ionized part of Earth’s atmosphere and the signals that pass through it,” says Phil Erickson, assistant director at Haystack and lead for the atmospheric and geospace sciences group. “These new results from Haystack-led studies are an excellent example of how much still remains to be learned about our atmosphere and its complex interactions through observing one of nature’s most spectacular sights — a giant active celestial experiment provided by the sun and moon. The power of modern observing methods, including radio remote sensors distributed widely across the United States, was key to revealing these new and fascinating features.”

The Great American Eclipse has come and gone, but the detailed data gathered during that 90 minute “celestial experiment” will be examined by scientists for some time.

![The Viking 2 lander captured this image of itself on the Martian surface. The Viking Landers were the last missions to directly look for life on Mars. By NASA - NASA website; description,[1] high resolution image.[2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17624](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/608px-Viking2lander1-580x458.jpg)