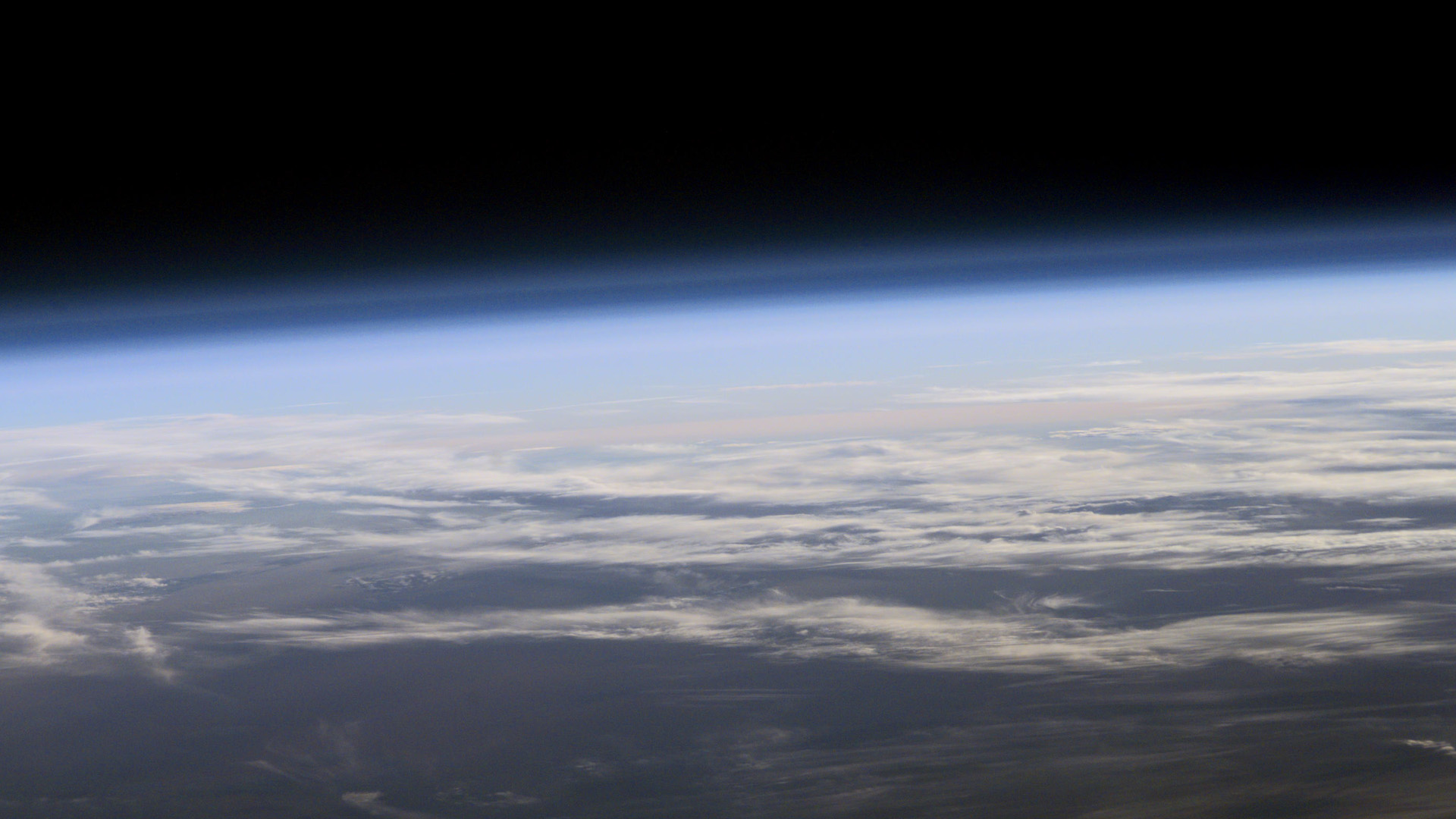

Orbital debris (aka. space junk) is one of the greatest problems facing space agencies today. After sixty years of sending rockets, boosters and satellites into space, the situation in the Low Earth Orbit (LEO) has become rather crowded. Given how fast debris in orbit can travel, even the tiniest bits of junk can pose a major threat to the International Space Station and threaten still-active satellites.

It’s little wonder then why ever major space agency on the planet is committed to monitoring orbital debris and creating countermeasures for it. So far, proposals have ranged from giant magnets and nets and harpoons to lasers. Given their growing presence in space, China is also considering developing giant space-based lasers as a possible means for combating junk in orbit.

One such proposal was made as part of a study titled “Impacts of orbital elements of space-based laser station on small scale space debris removal“, which recently appeared in the scientific journal Optik. The study was led by Quan Wen, a researcher from the Information and Navigation College at China’s Air Force Engineering University, with the help of the Institute of China Electronic Equipment System Engineering Company.

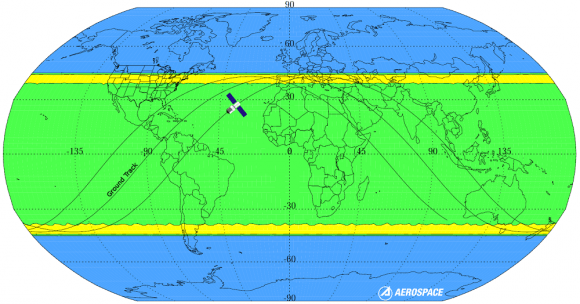

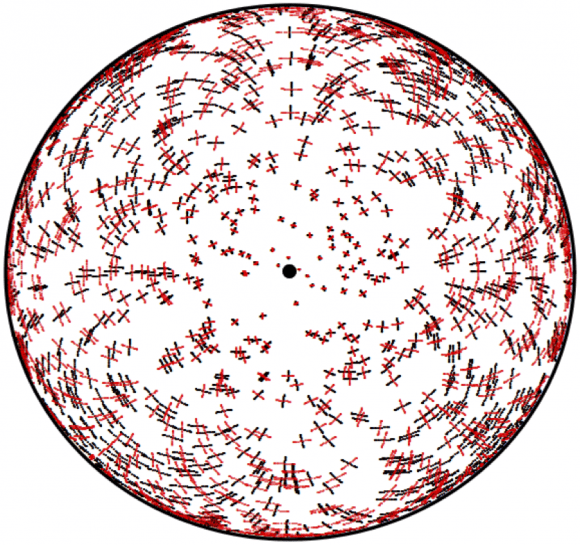

For the sake of their study, the team conducted numerical simulations to see if an orbital station with a high-powered pulsed laser could make a dent in orbital debris. Based on their assessments of the velocity and trajectories of space junk, they found that an orbiting laser that had the same Right Ascension of Ascending Node (RAAN) as the debris itself would be effective at removing it. As they state in their paper:

“The simulation results show that, debris removal is affected by inclination and RAAN, and laser station with the same inclination and RAAN as debris has the highest removal efficiency. It provides necessary theoretical basis for the deployment of space-based laser station and the further application of space debris removal by using space-based laser.”

This is not the first time that directed-energy has been considered as a possible means of removing space debris. However, the fact that China is investigating directed-energy for the sake of debris removal is an indication of the nation’s growing presence in space. It also seems appropriate since China is considered to be one of the worst offenders when to comes to producing space junk.

Back in 2007, China conducted a anti-satellite missile test that resulted in the creation over 3000 of bits of dangerous debris. This debris cloud was the largest ever tracked, and caused significant damage to a Russian satellite in 2013. Much of this debris will remain in orbit for decades, posing a significant threat to satellites, the ISS and other objects in LEO.

Of course, there are those who fear that the deployment of lasers to LEO will mean the militarization of space. In accordance with the 1966 Outer Space Treaty, which was designed to ensure that the space exploration did not become the latest front in the Cold War, all signatories agreed to “not place nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in orbit or on celestial bodies or station them in outer space in any other manner.”

In the 1980s, China was added to the treaty and is therefore bound to its provisions. But back in March of 2017, US General John Hyten indicated in an interview with CNN that China’s attempts to develop space-based laser arrays constitutes a possible breach of this treaty:

“They’ve been building weapons, testing weapons, building weapons to operate from the Earth in space, jamming weapons, laser weapons, and they have not kept it secret. They’re building those capabilities to challenge the United States of America, to challenge our allies…We cannot allow that to happen.”

Such concerns are quite common, and represent a bit of a stumbling block when it comes to the use of directed-energy platforms in space. While orbital lasers would be immune to atmospheric interference, thus making them much more effective at removing space debris, they would also lead to fears that these lasers could be turned towards enemy satellites or stations in the event of war.

As always, space is subject to the politics of Earth. At the same time, it also presents opportunities for cooperation and mutual assistance. And since space debris represents a common problem and threatens any and all plans for the exploration of space and the colonization of LEO, cooperative efforts to address it are not only desirable but necessary.