Remember the Hubble Space Telescope’s Deep Field and Ultra-Deep Field images?

Those images showed everyone that what appears to be a tiny, empty part of the sky contains thousands of galaxies, some dating back to the Universe’s early days. Each of those galaxies can have hundreds of billions of stars. These early galaxies formed only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. The images inspired awe in the human minds that took the time to understand them. And they’re part of history now.

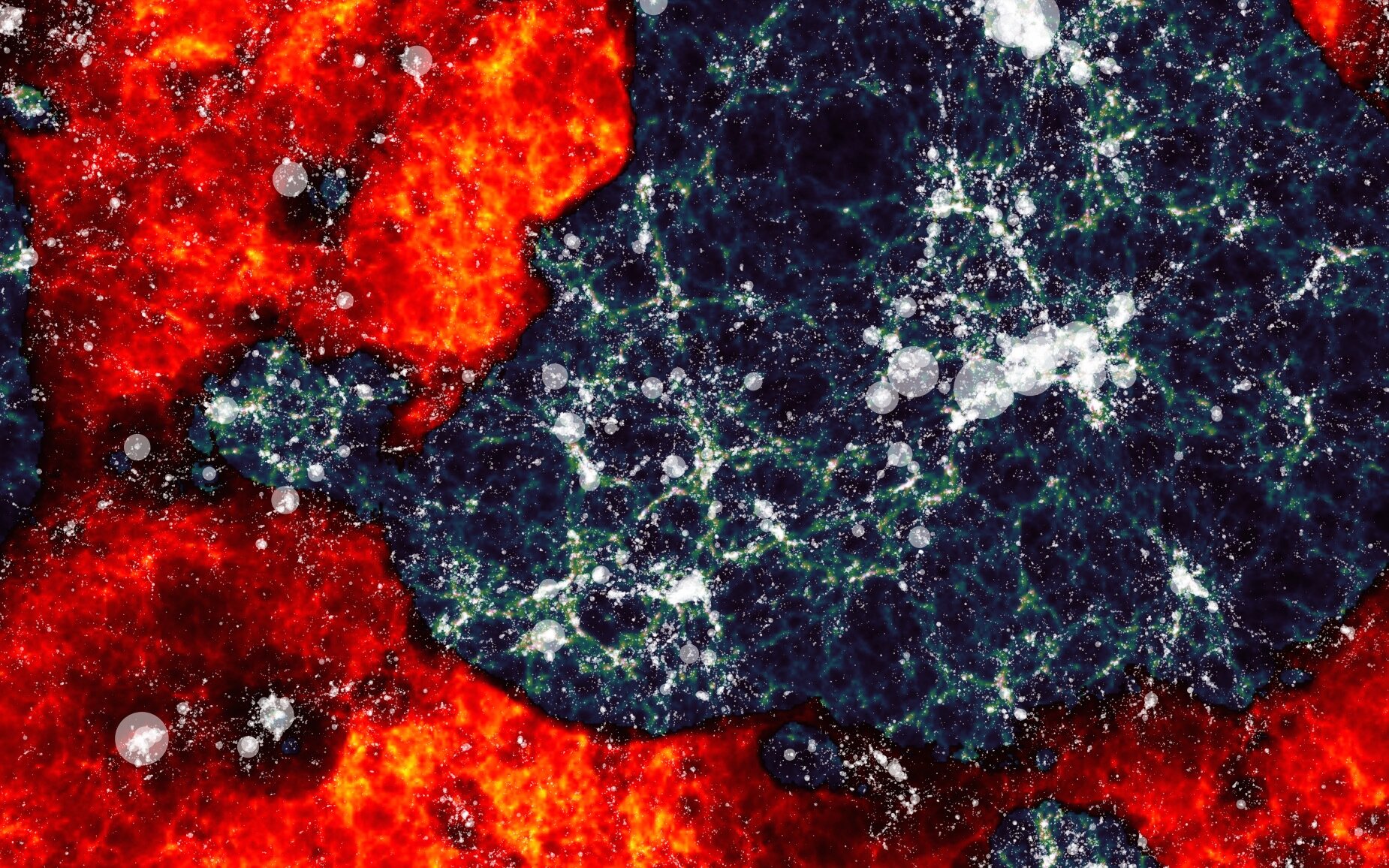

The upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope (NGRST) will capture its own version of those historical images but in wide-angle. To whet our appetites for the NGRST’s image, a group of astrophysicists have created a simulation to show us what it’ll look like.

Continue reading “Nancy Grace Roman Telescope Will do its Own, Wide-Angle Version of the Hubble Deep Field”